Greece fell to the Nazis over 80 years ago. Ross J. Robertson writes about this dark moment in modern Greek history.

Wehrmacht forces invaded Greece on 6 April 1941. It was Hitler’s response to Mussolini’s unsanctioned and largely inept 28 October 1940 incursion and the ensuing Greek counterattacks which drove the Italians back deep into Albania in the very first Allied ground-based victory of the war.

In every other respect, circumstances for the Allies were truly desperate. Continental Europe had all but fallen to the Nazis and their tyrannical regime. Britain had barely staved off invasion by frantically pitting the ‘so few’ against the Luftwaffe in the Battle of Britain. Any gains made in North Africa were being lost to (then) Lt General Erwin Rommel and his infamous Deutsches Afrika Korps (the siege of Tobruk would start on 10 April). German U-boat wolf packs were wrecking havoc on the newly agreed transatlantic lend-lease supplies. Above all, America remained defiantly neutral (Pearl Harbour was another eight months away), dashing any hope turning the unremitting fascist tide.

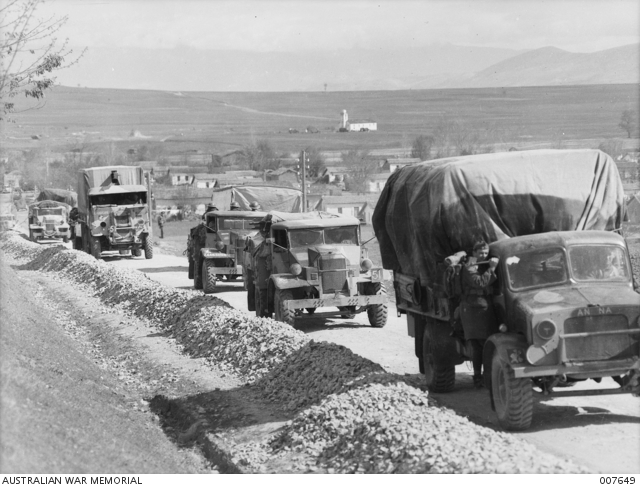

Despite successes against the Italian incursion, Greece remained vulnerable, not least because it was short of men, equipment and munitions. In compliance with a 1939 treaty, the British stepped in to help as best they could, first sending a few Royal Air Force (RAF) squadrons, and later (in March 1941) the British Expeditionary Force – a hasty extraction of about 65,000 mostly British and Commonwealth troops (the bulk of whom were Australian and New Zealanders) from the North African campaign.

The RAF deployment was particularly worrying for the Germans. The Romanian oil fields, upon which the might of the Nazi military machine heavily depended, could now be attacked by British long range bombers, should they be stationed in northern Greece. In fact, there were no airfields in the north capable of facilitating such a plan, nor were any aircraft, equipment or personnel available. Until March 1941, the Greek government had been careful not to provoke German wrath by limiting British presence and activity. This even extended to forbidding the RAF from surveying areas north of Mount Olympus for suitable airfield sites. Nevertheless, the threat loomed large enough for Hitler to order ‘Operation Marita’ – the blitzkrieg of Yugoslavia and Greece – into action.

“They struck the Metaxas Line at dawn on 6 April 1941.”

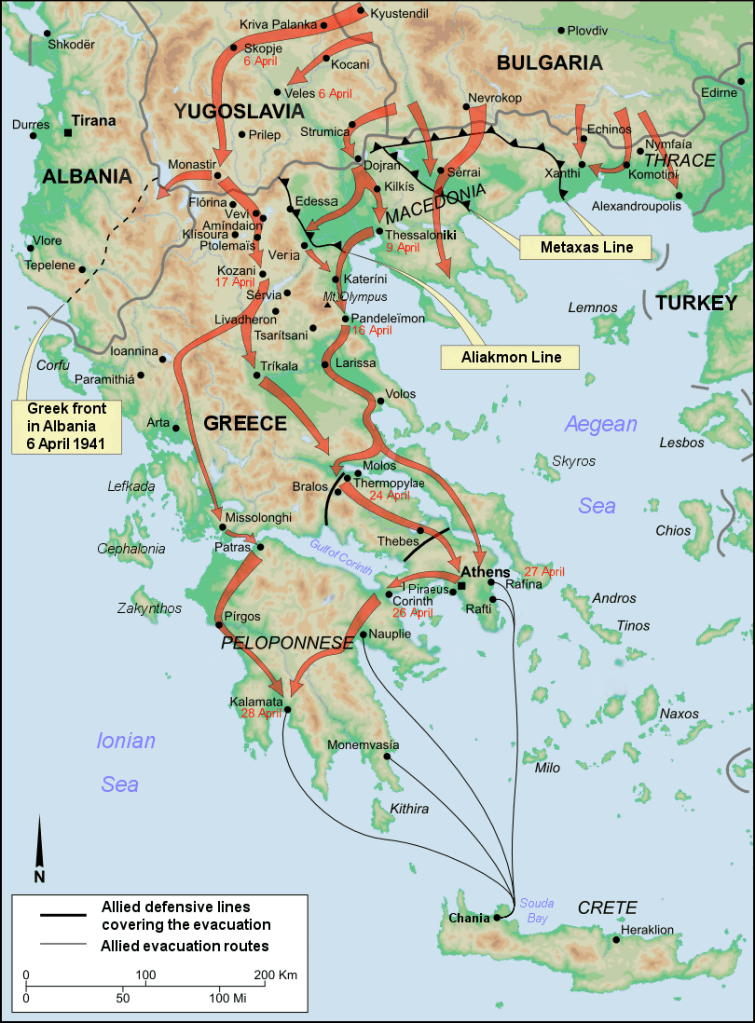

Most of the Greek army faced off the Italians in Albania, leaving the rest of the country lightly defended. While Yugoslavia and Turkey remained neutral, the Bulgarians had sided with the Axis powers a month earlier, allowing the Germans to amass troops along the border in preparation. They struck the Metaxas Line at dawn on 6 April 1941. Although vastly outnumbered, the Greeks led by Brig Gen Konstantinos Bakopoulos held back the invaders for several days, only to be outflanked when German 2nd Division Panzers swept through Yugoslavia. By the 9th, Thessaloniki had fallen, cutting off the defenders and forcing capitulation. However, German commander Field Marshal Wilhelm List was so impressed by the courage exhibited by the Greeks (and certainly less impressed by the logistical problems so many POWs would create) that he allowed them to go free after disarmament.

Having taken Yugoslavia, the 5th Panzer Division entered Greece and engaged at Vevi Pass, near Florina on the 11 April, wreaking considerable havoc on the 6th Division Australians defenders. They continued to push south, capturing Kozani on the 14th after the only tank battle of the campaign – 32 British tanks lost to only 4 panzers. Although further advance was hindered for three days by intensive fire from defensive mountain positions, the Germans had now effectively driven a wedge between the British Expeditionary Force and the Greek First Army fighting in Albania.

“32 British tanks lost to only four Panzers”

Outgunned, outflanked and outwitted, withdrawal had become the only option. Expeditionary commander Lt General Henry ‘Jumbo’ Wilson (who was also in charge of two Greek Infantry Divisions) ordered the British and Australian forces to head for Mt. Olympus to take up defensive positions with their 2nd Division New Zealand comrades-in-arms.

from the Monastier gap. 13 April 1941.

Meanwhile, the Greek First Army, who were reluctant to concede ground to the Italians, started a belated withdrawal from Albania on the 13th, heading south along the Pindus Mountains. While the Italians were slow to capitalise on the situation, the Germans hounded the Greek retreat, striking hard on their flank at Kastoria Pass and elsewhere. The 1st SS Motorised Infantry Regiment rushed ahead to Yannina to encircle the retreating troops, a feat they achieved after a fierce battle high in the mountains near Metsovo on the 20th. Dispirited by defeat and facing serious problems of shortages and desertion, Greek commander Lt Gen Georgios Tsolakoglou surrendered. Honourable terms were granted by the Germans (Tsolakoglou refused surrender to the Italians until forced to later) out of respect for their bravery and, once again, no prisoners were taken.

(146-1994-009-17) German Federal Archives ©

The British strategy became a series of rearguard actions, notably at Platamonas (a narrow pass between the Olympus Mountains and the Aegean where the 21st Battalion New Zealanders with only four 25 pound guns faced the 9th Panzer Division with 100 German tanks and two battalions of infantry) and Pinios Gorge (a passage leading to the Plain of Thessaly, Larisa and Volos port). Orchestrated with the strategic demolition of roads, bridges and railway tunnels, each was designed to hinder the German advance southwards and enable a general evacuation of the mainland.

Photo by Mr H. Hensser, (CM873) IWM ©

On 15 April, those defending Mt. Olympus were ordered south to make a last stand at Thermopylae, famous for the defiance shown by 300 Spartans against the Persians in 480 BC (actually, an alliance of some 7,000 men from various Greek states were involved). After several heavy engagements, including at Brallos Pass where Australians suffered heavy casualties, the defenders managed to slip away on the nights of 24 and 25 April before the Germans had a chance to outflank them via the Molos road and mountainous terrain to the west.

Apart from later skirmishes at Thebes, the fall of Thermopylae fundamentally left the road to Athens open for the Germans. However, the Expeditionary Force, who were equipped for desert warfare and not mountainous Greek terrain, had managed to maximize topography to their advantage throughout the fighting withdrawal, thereby succeeding in their mission. Now it was time to leave, if they could. The main evacuation ports were at Volos (captured on the 21st, along with large quantities of fuel), Chalkis, Porto Rafti, the naval base at Salamis (the future site of Germany’s first U-boat base in the Mediterranean), Megara, Nafplio (in Peloponnese) and Piraeus.

The Luftwaffe played a pivotal role at each stage of the invasion. Ju-87 ‘Stuka’ dive-bombers in particular helped break the Metaxas Line as well as raging effective attacks on other Greek and Expeditionary positions. Significantly, the Luftwaffe seriously affected evacuation efforts. It sunk some 200 ships in April, including several vessels laden with evacuating troops.

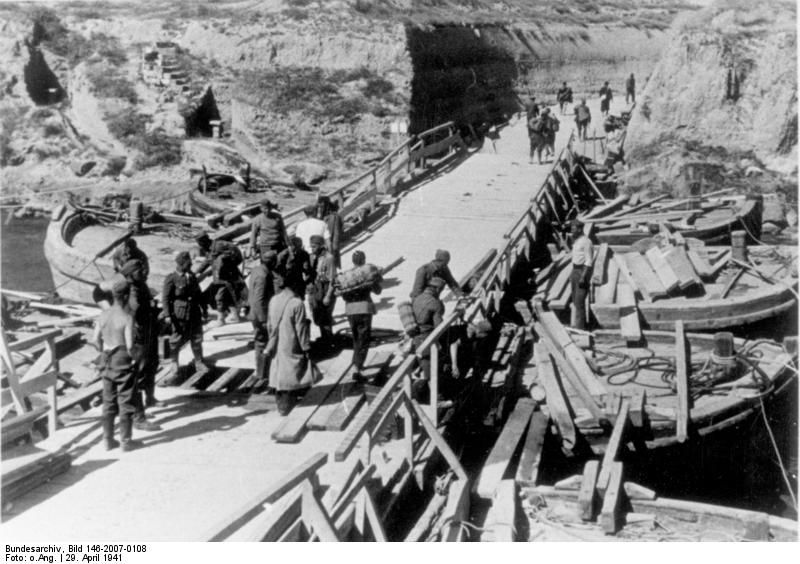

For those who had not already embarked a ship for Crete or Egypt, the only chance of escape was to cross the Corinth Canal and head for the southern most towns of the Peloponnese. To foil this, an air operation involving some 400 transport planes and gliders was hastily staged from Larisa airfield (captured on the 19th with fuel and British supply dumps still intact) on the 26th. While the gliders landed troops to secure both sides of the canal, 800 parachutists seized the bridge, taking the British by surprise and capturing many in the process. Realising that the bridge had been wired, the Germans simply disconnected the fuse. However, before the charges could be dismantled, a stray British shell struck, blowing the bridge sky-high and taking numerous Germans with it.

On the 27th, the first Germans entered Athens, encountering no resistance. Not much time was lost before the swastika was flying high on the Acropolis. The inventors of blitzkrieg had proven once again to the world that they were the masters of its execution.

Photo by Heinrich Hoffmann, (HU39532) IWM ©

(101I-165-0419-19A) German Federal Archives ©

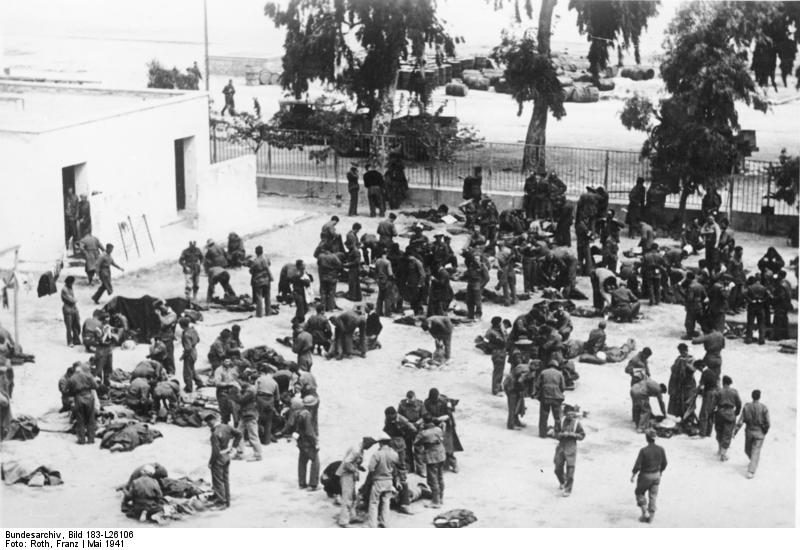

The plight of the evacuees continued. German engineers soon laid down a temporary bridge across the Corinth Canal and the panzers rolled into the Peloponnese, hot in pursuit. By this time, the Germans had made it across to Patras as well. Although there were skirmishes, the remnants of the Expeditionary Force were focused on evacuation via Kalamata on the southern coast. The German 5th Panzer Division engaged on the 28th, even as many Australians and New Zealanders still awaited transport to Crete and safety.

Although some 50,000 Allied troops had been saved, as many as 8,000 were eventually forced to surrender and taken prisoner. By the end of the month, the mainland was securely in German hands. It had taken a mere 24 days.

However, the ordeal was not quite over; the Battle for Crete would soon follow.