10 June 1944

– a ww2stories.org English exclusive –

June 2024 marks the 80th anniversary of the Distomo Massacre, a Nazi atrocity against a tranquil Greek mountain village. Unsettling truths have emerged, challenging the official narrative. Join Dr Konstantinos Giannakos and Ross J. Robertson as they uncover the reality behind the loss of innocent lives to unspeakable violence.

The authors wish to thank Brigadier Roger Dillon, RM (ret’d), son of WWII SOE liaison officer Major Brian Dillon MBE, for permission to use his late father’s personal archive.

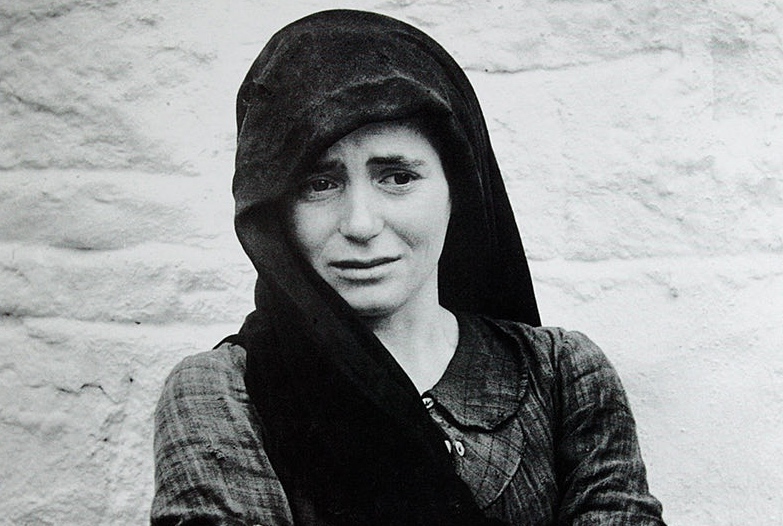

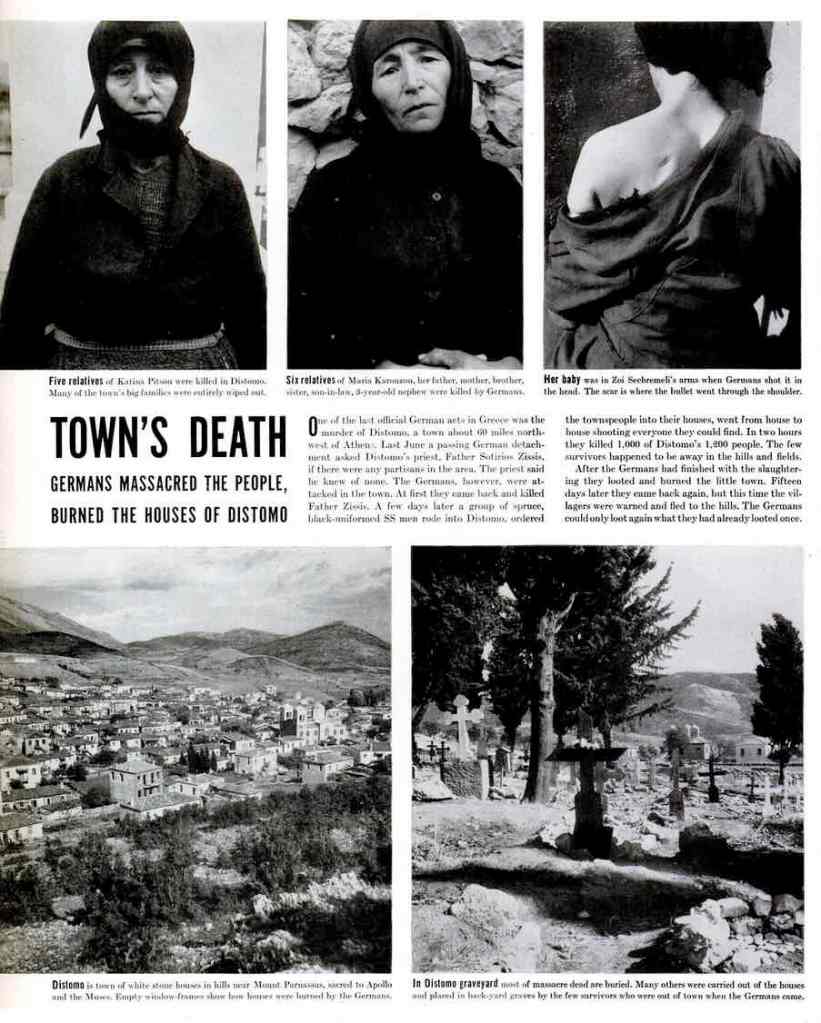

Source: LIFE Magazine ©

In Chaos Theory there is a poetic metaphor which is known as ‘The Butterfly Effect’. According to this concept, there is sensitive dependence on initial conditions, meaning that a small change in one state of a deterministic nonlinear system can result in large differences in a later state. In real life, warfare epitomises the application of the Chaos Theory par excellence. In the context of the subject title, the landing on a French coast on 6 June 1944, of a young man from Middlesbrough, together with tens of thousands of other men from the UK, US and other countries, led to the horrific massacre of innocent civilians in Distomo, an obscure Greek village in Boeotia, four days later.

The events of the massacre are well-known and documented. On Saturday 10 June 1944, the 2nd Company of the 1st Battalion of the 7th Panzergrenadier Regiment, part of the 4th SS Polizei-Panzergrenadier-Division, stationed at Livadia, Boeotia, set out for another anti-partisan sweep, travelling in seven trucks. 1 At the intersection of the Distomo–Arachova road, they came across another German convoy coming from Amfissa and heading to Distomo. After consultations between the two commanders, the combined column proceeded to Distomo. The villagers were caught off guard, but some locals started to feel uneasy due to the large size of the German force and the presence of hostages among them, who had been captured earlier. When the Germans received information about the presence of anti-partisan guerrillas at Steiri, they sent a detachment to investigate. Shortly before the village they ran into an ambush, where they sustained a number of casualties. After the guerillas retreated, the column returned to Distomo.

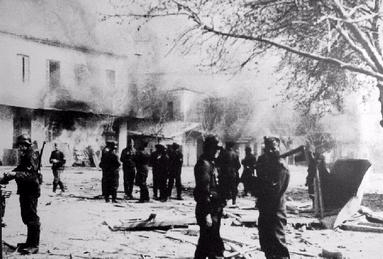

There, the German on-scene commander, Captain Fritz Lautenbach, ordered reprisals – Vergeltungsaktion, in German – against the civilian population, as per standing orders. The first to be executed were the 12 hostages, who were shot in front of the Elementary School. Then, the carnage began in earnest. German soldiers went berserk and started going door-to-door, shooting, bayoneting or grenading the people locked in their homes. The ones to escape the massacre were those lucky enough to live on the outskirts and had time to flee through Diaskelo, the only unguarded pass. Even the animals did not escape the Nazis, as they shot or burned cows, dogs, sheep, horses, and so on. The atrocities ended at dusk, when the troops departed for their base, fearing a possible guerrilla ambush.

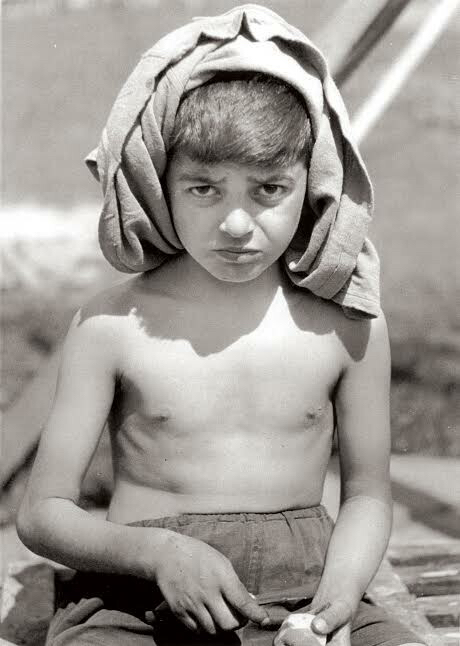

The official number of the murdered at Distomo was 228 people (117 women and 111 men), including 53 children under the age of 16. The scenes that greeted the Swedish Red Cross representative Sture Linnér upon reaching the village right after the massacre were horrifying and reminiscent of a painting by Hieronymus Bosch. Mutilated corpses, others being nailed to trees, babies cut to pieces in their cribs – there was evidence of indescribable savagery everywhere. The events at Distomo caused a crisis between the Quisling government of Ioannis Rallis and the German Occupation authority, which after pressure from the Reich Plenipotentiary Hermann Neubacher, was forced to order an investigation. Georg Koch, who was a member of the Geheime Feldpolizei (GFP Gruppe 510) accompanying Lautenbach’s company, wrote in his report that the latter was lying and that the German troops were fired upon several kilometres away from Distomo. However, there was no engagement whatsoever with guerrillas in the vicinity.

“The official number of the murdered at Distomo was 228 people,

including 53 children under the age of 16.”

At the same time, Major Brian Dillon, MBE, operated nearby. The British officer was serving with Special Operations Executive (SOE), the agency tasked to gather intelligence, create sabotage and raise, train, equip and/or cooperate with guerrilla troops in occupied countries.

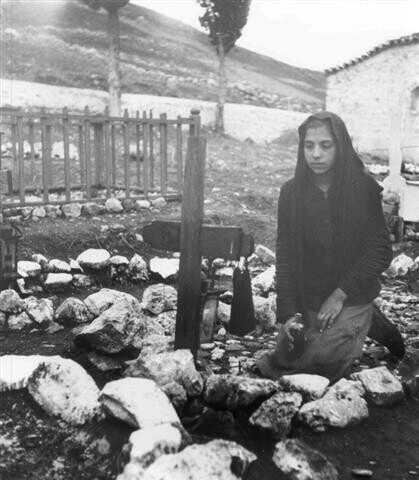

Source: lifo.gr

As is well-known, the first SOE mission in Greece took place on 25 November 1942, with the destruction of the Gorgopotamos viaduct (Operation HARLING). These initial 12 members formed the basis for the creation of the British Military Mission. Over the next months, more agents along with arms and equipment started arriving to the various resistance groups scattered all over Greece. This was the context of Dillon’s deployment. Although an infantry officer, initially commissioned in the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Norfolk Regiment (RNR) upon graduation from RMA Sandhurst in 1939, he was one of the first to join the fledgling Special Air Service (SAS) (L Detachment, SAS), while stationed in North Africa. He served with them from 1941 to 1943 and later he joined their offshoot, the newfangled Special Boat Squadron (SBS), and had the chance to meet and co-train with Greek commandos from the Sacred Band. As if serving in an elite unit like the SAS or the SBS was not enough, he opted to join the Greek Section of SOE at Cairo in early June 1943.

After several days of intense training, he was parachuted onto Mount Giona, armed only (according to his recollections) with a revolver, equipped with a compass, a pair of binoculars, 25 gold sovereigns, and a bottle of gin. Upon landing, he made contact with an ELAS band and met other fellow agents like Captains Arthur Edmonds, of Gorgopotamos fame, and Harry MacIntyre, who had just blown up the Asopos viaduct (Operation WASHING). Over the next few weeks, Dillon participated in sabotage activities, which were part of Operation ANIMALS, the deception plan aimed at sowing confusion in the German leadership concerning the next Allied landing, following their victory in North Africa. Dillon’s most notable feat during this period was the demolition of the bridge at Steno gorge (Dorida area), which today is under the Mornos Reservoir, together with Captain Geoffrey Gordon-Creed, also from Operation WASHING. The result was the severance of the Amfissa–Nafpaktos road.

After the completion of Operation ANIMALS (July 1943), due to the allied landings in Sicily (Operation HUSKY), Dillon moved to Mount Helicon (Boeotia), where he established Lillian Station, which functioned as a yafka. It was in his capacity as station commander and following many harrowing experiences, which are not relevant to the story, that the Normandy landings took place. When he learned about them, he thought it propitious to start touring the villages in his Area of Operations (AO), spreading the good news. This was in accordance with one part of his mission, i.e. to wage PsyOps (Psychological Operations) on the locals, trying to raise their morale by saying that Liberation was near. On 6th June 1944, Dillon and his protection detail entered Desfina (Phocis), a village approximately 18 kilometres west of Distomo, in the direction of Amfissa, which is 32 kilometres away, to the northwest. They spent their night there, but the man in charge of the detail neglected to post sentries for early warning in case of a German foray. Next morning, while Dillon was having coffee on the veranda of the house where he spent the night, he saw with dread a German soldier aiming his rifle right at him. He immediately opened fire and, together with the other antartes (guerrillas), beat a hasty retreat towards the sea. There they enlisted an old man and his boat to ferry them across the gulf of Itea, to Galaxidi.

Source: lifo.gr

The so-called ‘Battle of Desfina’ (7 June 1944) resulted in the death of 23 guerrillas. Most of them were young members of the local Livadia branch of EPON (the United Panhellenic Organization of Youth or Ενιαία Πανελλαδική Οργάνωση Νέων in Greek), also called Eponites. This was a communist youth movement under EAM’s (the National Liberation Front or Εθνικό Απελευθερωτικό Μέτωπο) umbrella. Dillon stated that the commander of the 3rd Battalion/34th ELAS (the Greek People’s Liberation Army or Ελληνικός Λαϊκός Απελευθερωτικός Στρατός, the military wing of EAM) Regiment, furious from the loss of his men, gathered the rest of the battalion and force-marched them all night to Desfina. Upon reaching the area, he set up an ambush, in which 70 Germans were killed and an unknown number wounded, also destroying six trucks, according to Dillon’s report to Cairo. As he stated in his Imperial War Museum (IWM) interview (recorded in August 2002): “They [ELAS] really put up quite a smart show.”

The guerrilla raid infuriated the Germans, who on 10 June 1944 sent a whole SS battalion, numbering close to 600 men, on a punitive expedition in Desfina. But the commanding officer of the 1st Battalion/SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment 7, whom Dillon was later able to identify as Sturmbannführer Kurt Rickert, 3 reportedly used a Greek map to locate their target. He mistook Desfina for the closer village of Distomo. According to Dillon, “Distomo was entirely innocent, had nothing to do with any of this; the villagers were going about their work the normal way. The Germans surrounded the village and killed every man, woman and child and burnt it to the ground. A mistake – and I’ve had it on my conscience forever. If I hadn’t gone to Desfina, it would never have happened.”

“Distomo was entirely innocent,

– Major Brian Dillon MBE

had nothing to do with any of this.”

Dillon fought the Germans from the beginning to the end of the war, so he knew perfectly well that both the Wehrmacht and the SS served a wicked ideology. So they were unlikely to respect the lives of innocent civilians. Jörg Friedrich, in his book The Fire: The Bombing of Germany, 1940-1945 (2008), paraphrases Lord Acton’s famous quote about power, asserting that: “Total war consumes human beings totally – and their sense of humanity is the first to go.” The fact that after so many years of fighting, Dillon had managed to preserve his, at a time when everything around him said otherwise, speaks volumes about his character. In those days, the Germans were looking for ways to vent their frustration and despair for the coming defeat, which was all too plain to see. Sadly, even if Distomo had been spared, there would have been another village to suffer the same fate, as was the case not only in Greece, but throughout occupied Europe where the people had chosen to resist, preserving their dignity and claiming their freedom.

We value your opinion!

Your feedback is important to us. If you enjoyed this article and would like to see similar content, show your appreciation by clicking the ‘Claps’ icon below. Also, ensure you stay up-to-date with our latest articles by subscribing to our Newsletter. You’ll receive new posts directly to your email inbox. Thank you for your support!

‘History has to be shared to be appreciated’

Subscribe to our Mailing List. We’ll keep you in the loop.

Source: Wikipedia

Footnotes

- The 7th SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment was commanded by Standartenführer (Regimental Leader) Karl Schümers. On May 30th, 1944 the regiment was stationed in Lamia, 1st Battalion, with 1st and 2nd Companies in Livadia, 3rd Company in Petromagoula and 4th Company in Aliartos. The 3rd Battalion had its companies stationed in Amfissa, Itea and Arachova and two batteries covered the area between Gravia and Amphiklia.

↩︎ - Argyris Sfountouris is a Greek-Swiss physicist, educator, poet, and translator. He was just four years old when he survived the Distomo massacre, a brutal atrocity committed by Nazi forces. After losing most of his family in the massacre, Sfountouris was sent to an orphanage in Athens. He later moved to Switzerland, where he pursued his education and became a physicist. Sfountouris has dedicated decades to advocating for the acknowledgment of German war crimes and securing compensation for the victims. His tireless efforts have made him a prominent figure in the struggle for justice and historical recognition.

↩︎ - ‘Sturmbannführer’ is ‘Assault Unit Leader’, a rank equivalent to Major.

↩︎

Archival Material

Brian Edevrain Dillon, IWM sound archives, Reels 6 & 7, accessible at: iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80022012, 1 April 2024.

Books – Webpages

Μαζάουερ, Μ., Στην Ελλάδα του Χίτλερ: Η εμπειρία της Κατοχής, Αλεξάνδρεια, 1994, Αθήνα

Παπανδρέου, Ζ., Δίστομο 1944-2014: Η συλλογική διαχείριση της μνήμης του τραυματικού γεγονότος, στο Συλλογικό, Κατοχική βία, 1939 – 1945: Η ελληνική και ευρωπαϊκή εμπειρία, Εκδόσεις Ασίνη, 2016, Αθήνα

Συλλογικό, Δίστομο 10 Ιουνίου 1944: Το Ολοκαύτωμα, Σύγχρονη Έκφραση, 2010, Λιβαδειά

youtube.com/watch?v=O9g2A4sCxkg, 1 April 2024

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Distomo_massacre, 1 April 2024

boeotia.ehw.gr/forms/fLemmaBodyExtended.aspx?lemmaID=12768, 1 April 2024

boeotia.ehw.gr/Forms/fLemmaBody.aspx?lemmaid=12785, 1 April 2024

1944shop.com/contents/en-us/d217.html, 1 April 2024

distomo.gr/μουσείο-θυμάτων-ναζισμού/, 1 April 2024