Hitler’s Rise to Power

– A ww2stories.org Exclusive –

Following a visit by Ross J. Robertson, ww2stories.org delves into Munich, highlighting the city’s extraordinary role in Hitler’s rise to power and that of the Nazi Party.

Munich, the capital of Bavaria, holds a unique place in the history of the Third Reich as both the birthplace and a central hub of Nazi power. It was in Munich where Adolf Hitler began his meteoric rise, where the Nazi Party was formed, and where some of the earliest and most significant events of his political career took place.

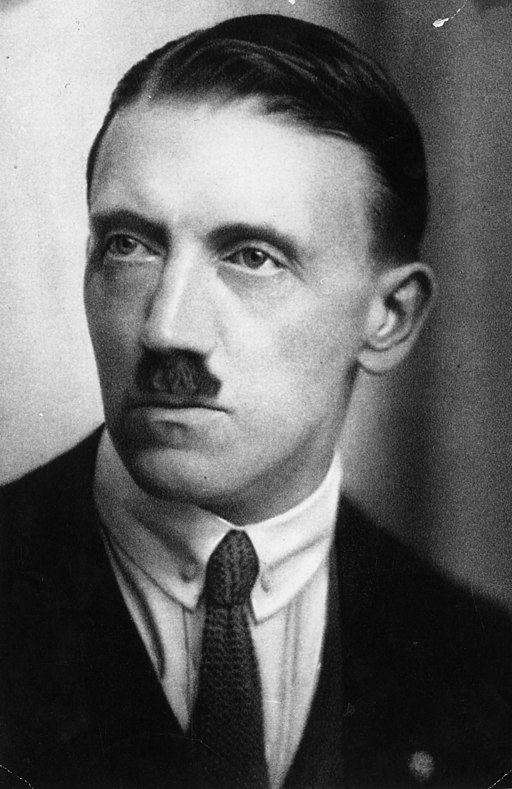

Adolf Hitler, a failed artist and drifter, moved to Munich in May 1913 at the age of 24. His move was likely motivated by a desire to avoid conscription into the Austrian Army, which he detested, but he may have also been attracted by the cultural atmosphere of Munich. Hitler was a passionate devotee of Richard Wagner, whose works often idealised a mythic and romanticised Germanically Bavarian past. This had a significant influence on Hitler’s later ideology.

When WWI broke out in August 1914, Hitler enlisted in the Bavarian Army, despite being an Austrian citizen. This was somewhat unusual, but it is believed that the Bavarian authorities either overlooked or were unaware of his nationality. Hitler served as a dispatch runner on the Western Front, where he was exposed to the brutal realities of modern warfare. His experiences in the trenches, including being gassed, coupled with a deep resentment over Germany’s defeat and the Treaty of Versailles, played a crucial role in shaping his extreme nationalist and anti-Semitic worldview.

Returning to Munich after the war as a demobbed Corporal, he was embittered and determined to restore his adopted Germany’s greatness. Through his war contacts, he was recruited by Captain Karl Mayr of the Reichswehr (the German military) to serve as an informant. Mayr tasked Hitler with infiltrating and spying on various radical political groups that were proliferating in Munich’s beer halls, a task which Hitler eagerly undertook. However, Hitler became genuinely interested in the ideas he encountered, particularly those of the German Workers’ Party (Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, DAP). Impressed by the party’s nationalist and anti-Semitic rhetoric, he decided to join in 1919.

Hitler’s impassioned rhetoric began to attract a significant following.

Munich’s beer halls became the backdrop for the Nazi Party’s early meetings and rallies, where Hitler’s impassioned rhetoric began to attract a significant following. His oratory skills and organisational talent quickly propelled him to prominence within the DAP. By 1920, he played a key role in rebranding the party as the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP), commonly known as the Nazi Party. Under his assumed leadership, the Nazi began to grow rapidly, laying the groundwork for an eventual rise to the top echelons.

Image: Public Domain

Hermann Göring was shot in the groin during the incident.

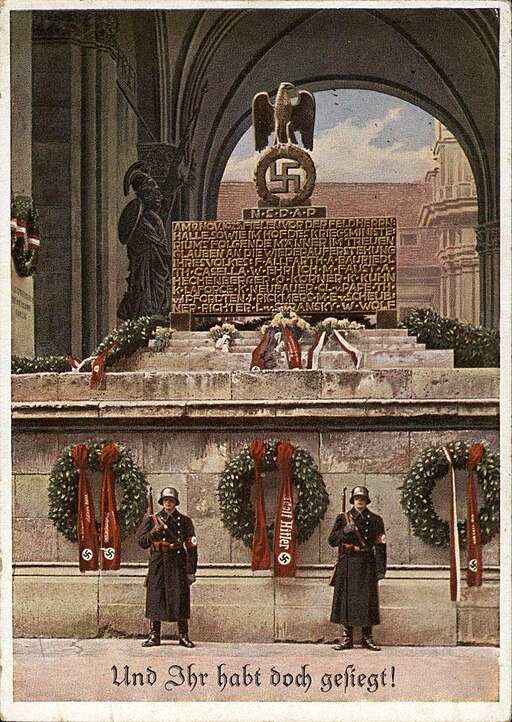

The Beer Hall Putsch of November 1923 marked Hitler’s first major attempt to seize power. This failed coup d’état, which began at the Bürgerbräukeller beer hall, ended in violence with the deaths of fifteen Nazis, four police officers and a bystander, Karl Kuhn, on Residenzstraße (Resident Street). Former WWI fighter ace and ardent Nazi supporter, Hermann Göring was shot in the groin during the incident. The injury led to a morphine addiction that plagued him for the rest of his life. However, his loyalty was rewarded and he later became Reichsmarschall Göring, the highest-ranking officer of the Luftwaffe during the Nazi regime. While the man next to him, Scheubner-Richter, was fatally shot, Hitler himself only suffered a dislocated shoulder and ran as fast as his ex-military dispatch runner’s legs could propel him. It can’t have been all that far as he was arrested 2 days later and sentenced to 5 years in prison for high treason, though he served only 8 months. During this time, he started writing Mein Kampf, a largely unreadable rant outlining his ideology and future plans for Germany.

It went on to sell over 12 million copies and was translated into 11 languages, earning Hitler an estimated 7.8 million Reichsmarks (i.e. millions of dollars today), although sales did drop off remarkably by 1945!

Despite the setback of the failed coup, Hitler and the Nazi Party continued to grow in influence, employing a combination of brutal ‘Brown Shirt’ thuggery and careful manipulation. During his initial rise, Hitler lived in a modest apartment at 41 Thierschstraße in Munich. As his power and wealth increased, he moved into a more luxurious apartment at 16 Prinzregentenplatz, which is now, perhaps ironically, a police station.

This luxury apartment was also the site of a tragic event in 1931, when his niece, Geli Raubal, with whom Hitler had a troubling and controlling relationship, committed suicide. Her death, surrounded by controversy and rumours, cast a lasting shadow over Hitler’s personal life even as his political influence expanded.

By 1933, the Nazis had become the largest political party in Germany, leading to Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor. After the death of President Paul von Hindenburg in 1934, Hitler consolidated his power by merging the offices of Chancellor and President, declaring himself Führer.

In other words, Hitler had well-and-truly arrived.

Munich’s significance to the Nazi movement extended beyond its role as the birthplace of the party. Even after Hitler moved to the Reich Chancellery in Berlin, Munich continued to be a major centre for Nazi administration and propaganda. The city remained pivotal for high-profile rallies and events that were crucial in promoting the party’s ideology and consolidating its power. Despite Nuremberg rallies, which were unparalleled Public Relations exercises in their own right, Munich’s designation as the ‘Capital of the Movement’ underscored its crucial role in shaping and disseminating Nazi propaganda and ideology.

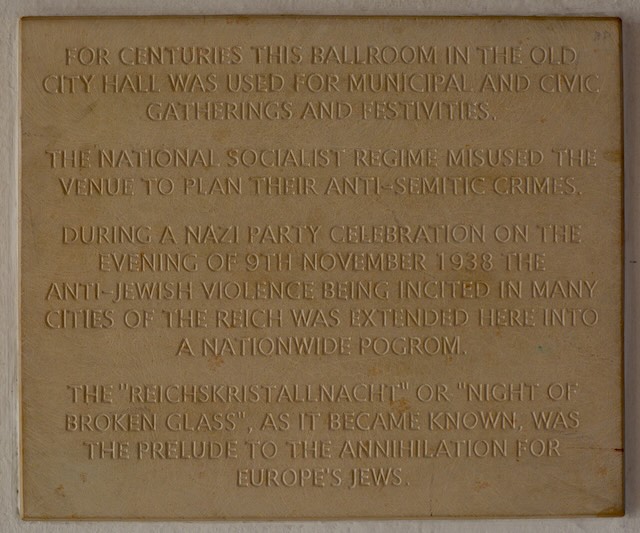

Moreover, Munich was the launch site for the Night of Broken Glass (Kristallnacht) on 9-10 November 1938. Joseph Goebbels, the Minister of Propaganda, orchestrated this nationwide pogrom against Jews, which marked a significant escalation in public anti-Semitic violence. The coordinated attacks resulted in the destruction of synagogues, businesses, and homes, as well as the arrest of thousands of Jewish men, who were sent to concentration camps. This event was a clear demonstration of the regime’s escalating brutality and its willingness to use violent measures to further its anti-Semitic agenda.

The Kristallnacht served as a grim precursor to the more systematic and widespread violence that would follow during the Holocaust. It also highlighted Munich’s role not just as a symbolic centre for Nazi ideology, but as a real-world hub from which some of the regime’s most brutal policies and actions were orchestrated. The city’s deep association with the Nazi movement thus marked it as a significant site in the history of Nazi Germany and its atrocities.

Image: Public Domain

It was near Munich, in the provincially small town of Dachau which lies not too far from the modern International Airport, that the Nazis opened their first concentration camp on 22 March 1933. Originally intended for political prisoners, Dachau became a model for the vast network of concentration camps that would follow, imprisoning a wide range of people deemed undesirable by the Nazi regime. Despite not being classified as a ‘death camp’, Dachau witnessed the cruel demise of approximately 41,500 prisoners before its liberation by American forces (7th Army, 45th Infantry Division) in April 1945.

Munich was also the site of one of the most significant assassination attempts against Hitler (there were quite a few). On 8 November 1939, Georg Elser, a German carpenter and anti-Nazi resistance member, planted a bomb at the Bürgerbräukeller beer hall with the intent to kill Hitler during his speech commemorating the Beer Hall Putsch. After meticulously planning for over a year, Elser hid a time bomb, plastering it inside a pillar near the speaker’s podium. Although Hitler delivered his speech as planned, he left the venue earlier than usual. The bomb exploded 13 minutes after Hitler’s departure, killing eight bystanders and injuring many others. Elser was subsequently arrested, imprisoned (i.e. relentlessly tortured), and eventually executed at Dachau in April 1945 on the Führer’s orders.

Image: Bundesarchiv ©

Image: Bundesarchiv ©

Image: Bundesarchiv ©

This was presumably part of an effort to tie up loose ends. The order was issued just weeks before Hitler took his own life on 30 April 1945. Interestingly, Hitler also found it necessary to poison his newly-wed, Eva Braun, and his beloved dog, Blondi, before also ingesting a hydrogen-cyanide capsule and pulling the trigger of a 7.65mm Walther PPK.

It did the trick – Hitler had now well-and-truly departed.

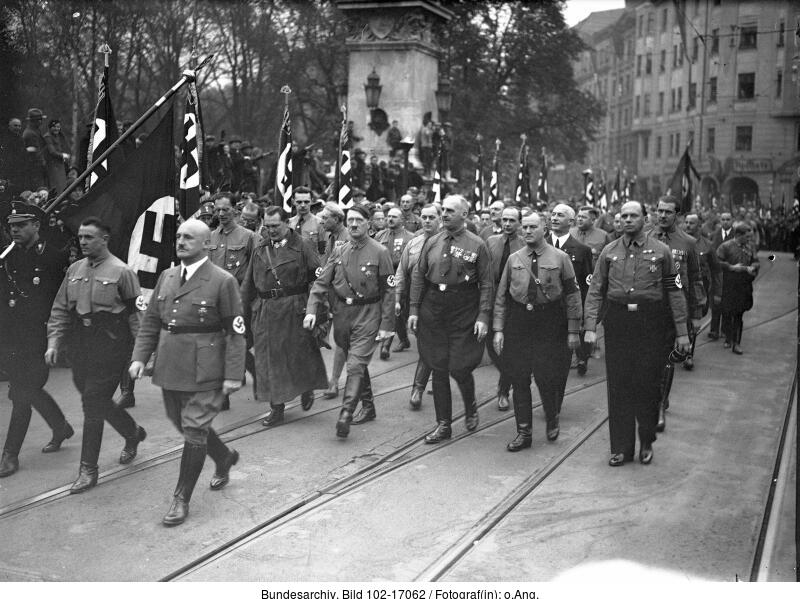

However, that was in the future. Munich was also the venue for an earlier assassinate attempt on 9 November 1938 which would have also radically changed modern history, had it been successful. Motivated by a deep opposition to Hitler’s policies, Maurice Bavaud, a Swiss theology student, travelled to Germany with the sole intent of killing the Führer und Reichskanzler (Leader and Chancellor of the Reich). He managed to position himself along the Putsch parade route, armed with a pistol. As Hitler passed by, Bavaud attempted to shoot him, but he was unable to get a clear shot due to the crowd and the distance between him and his target.

Bavaud’s foiled attempt went unnoticed at the time, but he was later arrested by the Gestapo for unrelated reasons. After being interrogated, he confessed to his assassination plan. He was tried and sentenced to death, and in May 1941, Bavaud was executed by guillotine in Berlin.

Image: Bundesarchiv ©

The attempt was made on Tal, the street that runs from the Isartor Gate to Marienplatz. Not so far down from this historical spot, a bustling McDonald’s does a brisk business in synthetic American food. Spoils always go to the conquerors.

Their activities ultimately led to their arrest and execution by guillotine.

The city was also home to the White Rose, a resistance group led by university students Hans and Sophie Scholl. The group was dedicated to non-violent opposition to the Nazi regime and distributed leaflets calling for resistance. Their activities ultimately led to their arrest and execution by guillotine in 1943, making them symbols of courage and resistance in the face of tyranny.

During WWII, Munich remained important to the Nazi Party, even as most operations moved to Berlin. As the war drew to a close, the city was heavily bombed by the British Royal Air Force (RAF) and the United States Army Air Force (USAAF), resulting in over 6,600 deaths and significant destruction. Despite this, Munich was meticulously rebuilt after the war, largely restoring the city to its pre-war appearance.

Most remnants of Nazi influence have been deliberately erased from the city. Despite the destruction caused by the assassination attempt, Bürgerbräukeller beer hall survived Allied bombing and was owned by Löwenbräu Brewery until it was pulled down in 1979 and replaced by city planners with the Gasteig Cultural Centre. Today, the site can be found a few metres behind the Munich City Hilton Hotel. There is a plaque set in the ground, but as it is only in German, it hides in plain sight to most visitors.

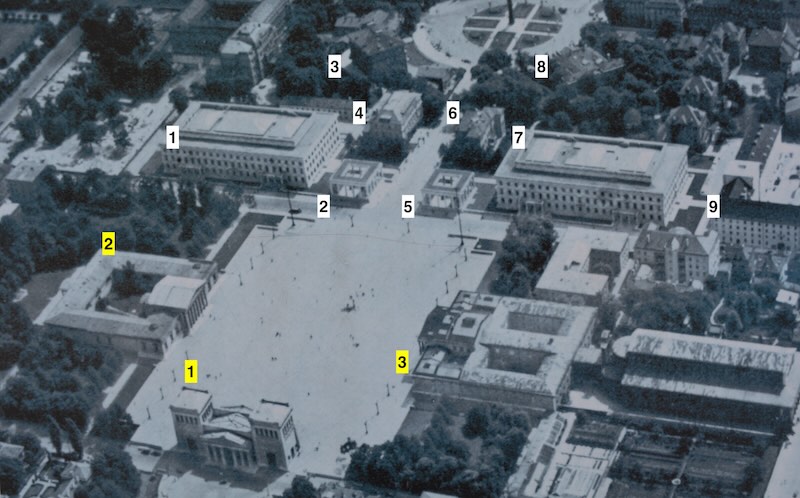

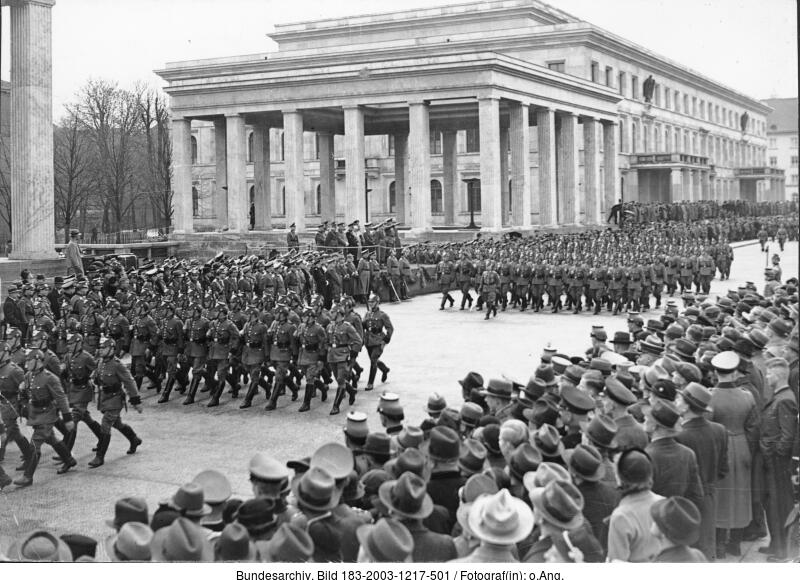

However, some locations remain intact, thus serving as stark reminders of this dark chapter in history. Königsplatz (King’s Square), constructed in the 19th century, is renowned for its Neoclassical architecture, including the Propyläen Gate and, directly opposite each other, the Glyptothek (an Archaeological Museum) and the Staatliche Antikensammlungen (State Collections of Antiquities). This impressive and monumental square was later repurposed during the Third Reich for Nazi Party mass rallies, including infamous book burnings. From 1931 to 1945, the Brown House, located at 45 Brienner Straße, served as the national headquarters of the Nazi Party. Its proximity to Königsplatz symbolised the Nazi assertion of power.

1. Propyläen (Propyläen Gate)

2. Glyptothek (Archaeological Museum)

3. Staatliche Antikensammlungen (State Collections of Antiquities)

Nazi Buildings

1. Führerbau (Führer Building)

2. Nördlicher Ehrentempel (Northern Honour Temple)

3. Oberster Parteigerichtshof (Supreme Court of the Nazi Party)

4. Braunes Haus (Brown House)

5. Südlicher Ehrentempel (Southern Honour Temple)

6. Büro des Stellvertreters des Führers (Offices of the Führer’s Deputy)

7. Verwaltungsbau der NSDAP (Nazi Administration Building)

8. Reichsrevisionsamt der NSDAP (Reich Auditor’s Office of the Nazi Party)

9. SS-Reichsführung (SS Reich Leadership)

Image: Dokumentationszentrum ©

Image: Bundesarchiv ©

The Nazi Party gradually acquired more properties in the Königsplatz area between Karlstraße and Gabelsbergerstraße, displacing local residents and creating a vast administrative centre where up to 6,000 people were employed. Even as political power shifted to Berlin, Munich remained the hub of the Party’s bureaucracy. By 1937, two ‘Temples of Honour’ for those who died in the Hitler Putsch, as well as monumental Party buildings such as the Führerbau (Führer Building) and the Verwaltungsbau der NSDAP (Nazi Administration Building), were completed. These buildings assumed many of the functions of the Brown House, which, nevertheless, continued to be the symbolic heart of the Party’s cult.

Image: NS-Dokumentationszentrum Museum

Today, the site of the former Brown House is home to the NS-Dokumentationszentrum (Documentation Center for the History of National Socialism), a museum and educational centre dedicated to examining the history and legacy of the Nazi regime. The Nazi Administration Building served as a collection point for the ‘Monuments Men’, where recovered paintings and other artworks, originally seized for the Führermuseum (an ambition never realised), were sorted. Today, this historic building houses the Central Institute for Art History. Both ‘Temples of Honour’ were demolished by the US Army in 1947, but their foundations can still clearly be discerned.

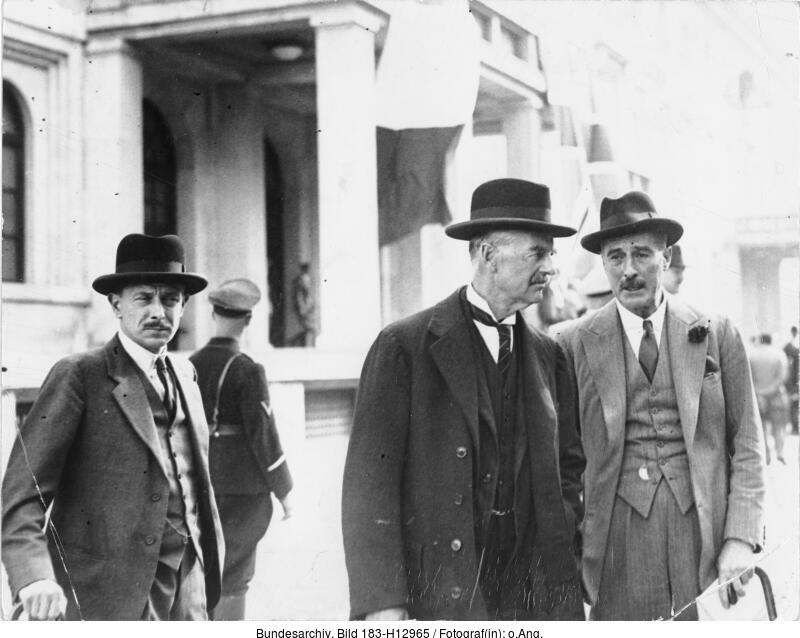

Visitors can still see the Führerbau, the building visited by the Duke and Duchess of Windsor in 1937 and where the ‘Peace for our time’ Munich Agreement was signed with British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain in 1938. It has now been repurposed as part of the Munich University of Music and Performing Arts – so not much of a departure in purpose then.

Image: Bundesarchiv ©

The Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site, located just outside Munich, stands as a solemn tribute to the victims of the Holocaust. Additionally, Munich is home to several museums dedicated to this period, including the Jewish Museum Munich, which explores Jewish life and history in the city, as well as the NS-Dokumentationszentrum, a museum dedicated to the history and impact of National Socialism.

One of the most prominent monuments from Nazi Germany that still stands today is the Feldherrnhalle (Field Marshals’ Hall) in central Munich, located on the Odeonsplatz. Originally commissioned by King Ludwig I of Bavaria in 1841 to honour the Bavarian Army, the structure was later co-opted by Adolf Hitler to commemorate 15 Nazis killed nearby on Residenzstraße during the failed Beer Hall Putsch of 1923. Hitler transformed the site into a memorial for these so-called ‘martyrs’, and the Odeonsplatz subsequently became a key venue for Nazi rallies, ceremonies, and propaganda events.

Image: Author 2024©

Image: Author 2024©

However, not everyone supported the regime, and

some chose to subtly resist.

Because of the monument’s significance, all passersby were required to perform the Nazi salute in front of a permanent police or SS Honour Guard and shrine. However, not everyone supported the regime, and some chose to subtly resist. To avoid giving the salute, these individuals would take a detour down Viscardigasse, also known as ‘Shirker’s Alley’. A trail of painted bronze cobblestones among the regular paving stones makes the path.

Visiting these sites and museums is important not only to remember the atrocities committed but also to ensure that the lessons of history are not forgotten. By confronting these remnants of the past, visitors can better understand the consequences of unchecked power and the importance of safeguarding democracy and human rights.

Munich’s role in the rise and administration of the Third Reich, as well as its place in the broader history of WWII, makes it a city of profound historical significance. The events that unfolded there not only shaped the course of the war but also left an indelible mark on the history of the 20th century.

We value your opinion!

Your feedback is important to us. If you enjoyed this article and would like to see similar content, show your appreciation by clicking the ‘Claps’ icon below. Also, ensure you stay up-to-date with our latest articles by subscribing to our Newsletter. You’ll receive new posts directly to your email inbox. Thank you for your support!

‘History has to be shared to be appreciated’

Subscribe to our Mailing List. We’ll keep you in the loop.

Footnotes:

- The Reichsadler, or ‘Imperial Eagle,’ is a heraldic symbol derived from the Roman eagle standard. It was used by the Holy Roman Emperors, later adopted by the Emperors of Austria, and is featured in the modern coat of arms of Austria.

During the Nazi era, two stylized versions of the Reichsadler were used, both clutching a swastika. The Reichsadler, adopted as the national emblem in 1935, had its head turned to the eagle’s right (the viewer’s left), symbolising the state’s authority. In contrast, the Parteiadler, or ‘Party Eagle,’ faced its head to the eagle’s left (the viewer’s right) and was used by the Nazi Party to signify its control. The differing head directions were used to distinguish between the authority of the state and the dominance of the party. ↩︎

Cover Photo: Marienplatz featuring the Town Hall in the Old City. Image: Author 2024©