The Crown of the Nazi’s Second Seat of Power

– A ww2stories.org Exclusive –

Join Ross J. Robertson for a ride in Hitler’s personal ‘gold’ elevator as ww2stories.org ascends the dizzying heights of the Eagle’s Nest, uncovering the remarkable history behind this infamous symbol of Nazi power and dominance.

Part I: The Eagle’s Nest 1938

Perched atop Kehlstein Mountain in the Bavarian Alps, the Eagle’s Nest (Kehlsteinhaus) stands as a striking reminder of the Nazi regime’s ambition and architectural prowess. Constructed between 1937 and 1938, it was commissioned by Martin Bormann who was Adolf Hitler’s private secretary – one of the Nazi elite who wielded immense power due to his control over access to the Führer. Bormann, who oversaw all development in the area, envisioned the structure not merely as a building, but as a symbol of dominance – a luxurious alpine retreat that would both impress and intimidate.

The Eagle’s Nest is part of the larger Obersalzberg region, an area selected for its breathtaking scenery and strategic seclusion. Hitler had already established his personal retreat, the Berghof, there, and the region quickly transformed into a fortified enclave complete with SS barracks and other facilities to support the Nazi leadership. The choice of Kehlstein Mountain for the Eagle’s Nest was both symbolic and practical; its towering elevation offered a commanding panoramic view, a fitting metaphor for the regime’s desire to project power over both nature and its citizens.

Image: H. Hubert ©

Constructing the Eagle’s Nest was a remarkable feat of engineering and the route leading to it – known as Kehlstein Road (Kehlsteinstraße) – remains an often overlooked marvel. Carved from solid rock, the 6.5 kilometre road, with five tunnels and a single switchback, rises 700 metres to the peak, illustrating the regime’s technical and organisational capabilities. Completed in just 13 months, the road’s rapid construction involved over 3,500 skilled and unskilled labourers under contract. As with the construction of the elevator shaft and the facility itself, no slave labour was used. However, the workers faced crippling deadlines and last-minute design changes, often forcing them to toil around the clock, even during the heavy winter months. Rock falls and avalanches resulted in eight fatalities – a grim testament to the importance placed on this showpiece project.

The Eagle’s Nest was inaugurated on 20 April 1938, the Führer’s 50th birthday. It is therefore often described as a birthday gift for Hitler, although there remains some debate over this premise. Certainly, the Eagle’s Nest was originally intended to both serve as a diplomatic reception centre and a replacement for the Mooslahnerkopf Teehaus, a nearby tea house Hitler frequented in the afternoons for its tranquil setting. Located within half an hour’s walking distance of the Berghof, the Mooslahnerkopf provided a more personal retreat where the Führer could chat informally with key figures in his regime. Walking alongside him on its narrow paths was regarded as a high honour, a chance to discuss political plans and strategy in a relaxed setting.

Ironically, despite the grandeur and expense of the Eagle’s Nest – literally no detail was overlooked – Hitler only visited it a few more than a dozen times. His true preference remained the Berghof, which, with its own stunning views and actual ownership, held far greater personal significance. Its main room, designed by architect Alois Degano, famously featured a large, multi-paned window that could be lowered to the floor, transforming the interior space into a vast open-air balcony, offering an uninterrupted view of the alpine landscape.

Image: Bundesarchiv ©

The significance of what was seen out of the window, irrespective of whether an actual window framed it or not, harked back to a grandiose connection to the legacy of the First and Second Reichs (neither of these terms is considered part of normal historical terminology). This connection was deeply intertwined with the ideals personified by Wilhelm Richard Wagner, whose operatic masterpieces celebrated mythical Germanic heroes and the dominance of noble figures over others perceived as inferior.

For the Nazi elite, such imagery was not just a reflection of the past, but a vision of their desired future – an echo of the imperial glory and power that they sought to resurrect and embody. This vision was deeply rooted in their eugenics policies (i.e. a distortion of ‘the survival of the fittest’ theories by Darwin), which aimed to create a racially pure and superior ‘Aryan’ race through selective breeding and the elimination of those deemed ‘undesirable’.

The landscape below both the Berghof and the Eagle’s Nest served as a reminder of their self-perceived lineage, rooted in Wagnerian fantasies of Teutonic supremacy and the historical narratives of Germanic greatness, which were used to justify their eugenics policies and the atrocities committed in their name.

Image: Bundesarchiv ©

Although Hitler did not frequent the Eagle’s Nest, it was used by his inner circle. His girlfriend Eva Braun spent much of her time in Obersalzberg and used the Eagle’s Nest at will. Indeed, she lived a life of opulence but was fundamentally a prisoner, kept out of the limelight by design. In a life marked by isolation and control, Braun was rarely seen in public with Hitler, as he wanted to maintain his image as a solitary leader devoted solely to Germany. This isolation led to periods of depression and suicidal tendencies; she attempted suicide twice, once in 1932 and again in 1935.

Foreign dignitaries such as Benito Mussolini, the Italian dictator who was actually the progenitor of 20th century fascism, were among the select guests invited to the Eagle’s Nest. Mussolini’s visit, like others, was intended to showcase the Nazi regime’s power and prestige. The lavishness of the venue and the high-profile nature of these gatherings served to impress and solidify diplomatic ties, even as the world outside faced increasing turmoil.

Image: Public domain

The Eagle’s Nest was also used for social events, including the notable wedding of Eva Braun’s sister, Gretl Braun, to Hermann Fegelein on 3 June 1944. This lavish event took place just before the pivotal D-Day invasion on 6 June 1944, reflecting the stark detachment of the Nazi elite from the escalating global conflict. The opulence of the wedding contrasted sharply with the war’s harsh realities. Just a few days before his own suicide, Hitler ordered the execution of Fegelein, who had been implicated in alleged desertion and conspiracy, demonstrating the brutal and arbitrary nature of the regime’s justice right up to the very end.

The Obersalzberg area was extensively bombed on 25 April 1945 by the RAF. The Berghof and many other buildings were significantly damaged. However, the loss of life was negligible as Martin Bormann had ordered the construction of a network of tunnels between the major buildings. It included an entire contingency headquarters for the Reich Chancellery, should Berlin fall. This, of course, never came to pass. There were evacuation plans, with Hitler’s personal aircraft and pilots at the ready for immediate egress, but he had opted to stay in Berlin.

There remains significant controversy over who first reached the Eagle’s Nest in the final days of the war. American soldiers from Easy Company of the 101st Airborne Division were tasked with occupying Berchtesgaden, the location of Obersalzberg and the Eagle’s Nest. However, some claim that a small band of troops from the French 2e Division Blindée (2nd Armoured Division) hiked up the mountain on 4 May 1945, the tunnel leading to the elevator being blocked by snow, to reach the Kehlsteinhaus. They reportedly seized personal items belonging to Nazi leaders, including invaluable photographs, before the Americans arrived. If this account is accurate, the remaining fine wines, silverware, furniture, and fittings were left behind, only to be looted by the Americans. In acts of careless vandalism, US soldiers even chipped off pieces of the iconic red marble fireplace as war trophies. Regardless of who arrived first, both ignorance and shortsightedness resulted in the loss of artefacts which were undoubtedly of historical significance.

The ruins of the bombed-out buildings in the Obersalzberg area, including Hitler’s once-imposing Berghof, were little more than rubble and finally demolished in 1952, erasing much of the physical remnants of Nazi power. Yet, the Eagle’s Nest survived the destruction that befell so many other structures. Its survival can be attributed to the difficulty of hitting such an isolated and elevated structure perched on a peak, along with its relatively low strategic value. This preservation has allowed it to become one of the few intact monuments of the Nazi era.

Part II: The Eagle’s Nest Today

A visit to the Eagle’s Nest is an experience that combines excitement with deep historical resonance. The journey to its height of 1,834 m begins with a thrilling bus ride up the Kehlstein Road, a marvel of engineering that cuts through sheer rock faces and offers increasingly dramatic views of the surrounding alpine landscape.

Upon arriving at the bus terminus, visitors are immediately drawn into the eerie atmosphere of the Eagle’s Nest by the entrance portal to a long, dimly lit tunnel. The thick marble archway above bears the date ‘1938’ – a subtle yet powerful reminder of its true origins. A closer look at the hefty double brass doors reveals the faint etchings left by American and French soldiers who liberated the area in 1945. Beyond lies the 120 metre marble-lined tunnel, skillfully hewn out of the rock. Originally heated by air from a parallel service tunnel, it once served as the grand entryway for Nazi dignitaries chauffeured in Mercedes, who had to reverse all the way back out due to the lack of a turning circle at the end. Today, visitors must walk the length of the tunnel, their anticipation mounting with each step.

At the end of this journey, a side entrance immediately leads to a large circular, marble-lined room featuring a domed ceiling, green leather benches, and an ornate ‘gold’ elevator – Hitler’s personal ride to the heavens. Decorated with Venetian glass and intricate polished brass detailing, the elevator still evokes an air of opulence and power. It rises 120 metres through the heart of the mountain, carrying some 15 visitors at a time, offering an awe-inspiring ascent to the summit.

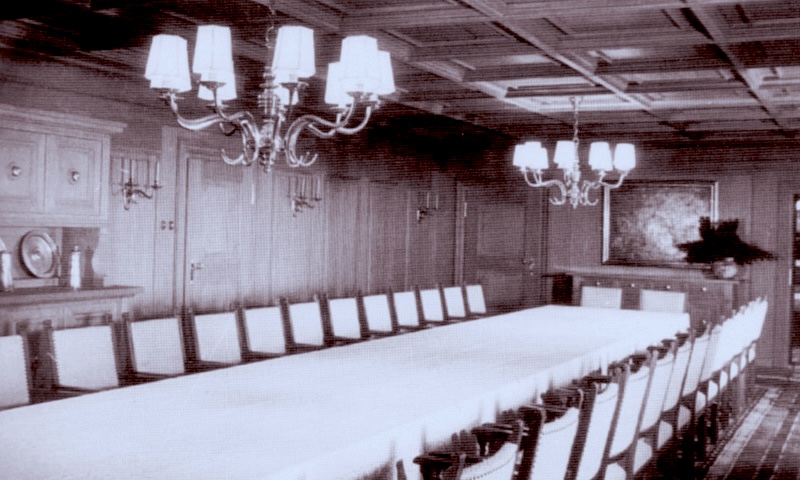

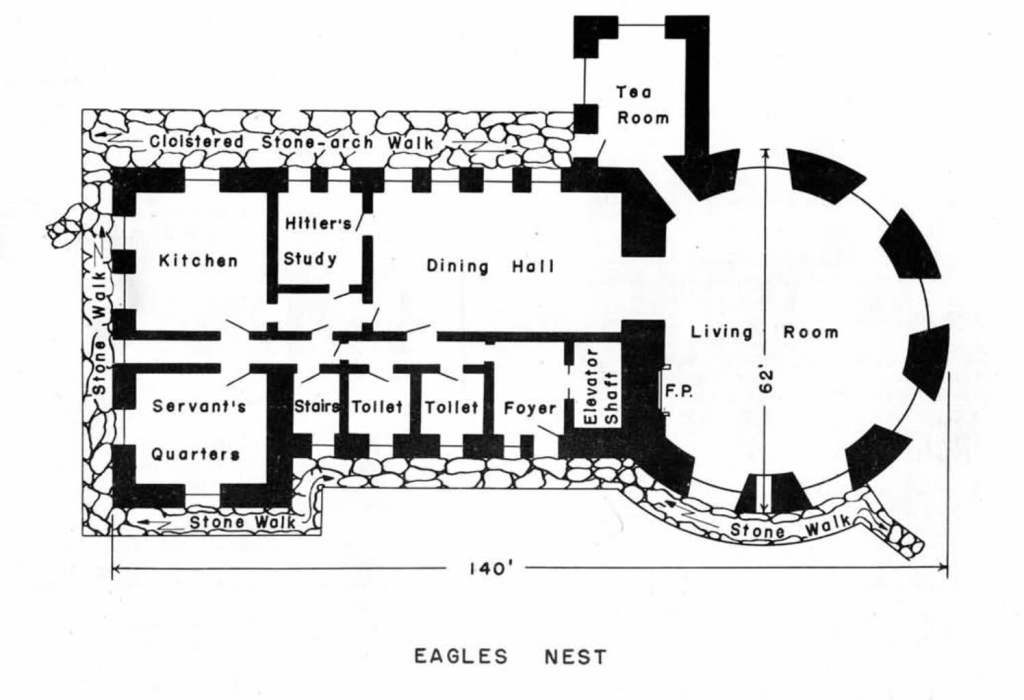

The experience of entering the Eagle’s Nest proper is both exhilarating and sombre. The elevator doors open into an entrance hall. From here it is possible to go straight outside, but a red marble-lined doorway on the right draws the curious into a sumptuous chestnut wood-lined area which was once the formal dining hall – the centrepiece of which was the large wooden table able to accommodate up to thirty diners. Behind this was a fully electric kitchen, a rarity for its time. Today, a restaurant serving breakfast and lunch operates in these areas, offering a unique dining experience.

A short flight of stairs leads down into the main reception hall. This large space (octagonal on the outside, but circular within), featuring its heavy timber-beamed ceilings, solid granite stonework (close to 2 metres thick), and six expansive windows offering a 270º panoramic view of the surrounding mountains and valleys, is truly awe-inspiring.

As you might expect, those six enormous windows were originally opened by being lowered into the basement using chains. In more recent times, they have been replaced with fixed glass panes.

However, the vista from the windows remains just as impressive as it ever was. The King’s Lake (Königssee) far below, its blue water cradled in a deep valley and glistening in the sunshine, immediately catches the eye. The prominent Austrian city of Salzburg, some 60 kilometres away, can also be clearly seen, as if just within reach. Austrian by birth and a failed artist by profession, Hitler saw the annexation of Austria (Anschluss) on 13 March 1938 as a pivotal moment in his ascent to power. He was here, in this very room, inaugurating the Eagle’s Nest just one month later.

The main reception hall features an impressive red Italian marble fireplace, believed to have been gifted by Mussolini, a testament to the regime’s extravagant taste. If Hitler ever roasted marshmallows, this is where he did it. The mantelpiece, vandalised by American troops as aforementioned, still defiantly bears the date ‘1938’ embossed into the firebox metalwork at the back.

Historically, this room was intended as an after-dinner space for informal conversations. A round table once stood before the fireplace, under which lay a decorative oriental-design carpet presented to Hitler by the Japanese Emperor Hirohito.

One can almost imagine the Nazi elite during the early part of the war, seated on designer furniture (most by Paul László) near the warmth of a blazing fire, glasses of the finest cognac pilfered from France in hand, discussing how terribly clever they all were as the new Masters of Europe.

During Gretl Braun’s wedding, the room was reconfigured with a huge banquet table. Today, it is furnished with heavy wooden tables and benches, effectively making it an extension of the restaurant.

I dined there for lunch in relative peace – surprisingly few came into the main reception hall and they tended not to stay long. Most visitors were enjoying the warm summer sunshine outside, while I contemplated the building’s dark history from within its walls. I was torn between the spectacular view outside the nearest picture window and the profound significance of my immediate surroundings. The juxtaposition of such beauty and such a dark past was striking, making the delightful meal both haunting and unforgettable.

Images: Public domain & Author ©

On the southern side of the reception hall, through an impressive doorway, a short flight of stairs leads to what is commonly referred to today as the ‘Eva Braun Room’. This much smaller space, lined with luxurious Swiss knotted pine panelling, features two large picture windows facing south and east. These offer stunning views of the Scharitzkehlalm – the room’s original namesake (Scharitzstube) – as well as the Königssee and the peaks of the Hohen Göll and Watzmann. Both windows could once be lowered almost completely, providing an unobstructed view of the breathtaking landscape outside. Today, they have been replaced by less remarkable fixed glazing.

The eastern door opens onto a long, low-walled sun terrace, offering another breathtaking picture-postcard view of the Königssee and the surrounding mountains through a series of five wide arches, which have since been enclosed with glass. This sun terrace now hosts a picture gallery of the Eagle’s Nest, showcasing its construction, the building of the access road, and various moments from its historical use.

Going back to the starting point on this tour of the Eagle’s Nest, directly opposite the elevator doors is a corridor leading to refurbished toilets on the left and what used to be servants quarters/guard room at the back. Beyond the former dining room is a shorter parallel corridor that led to an all white-tiled kitchen, again at the back. A door on the right of this corridor opened into an anteroom and Hitler’s personal study. This space, which Hitler never actually used, has now been repurposed as a simple storeroom and is not accessible to the public (see Delve Deeper below for a description).

Apart from actual foundations, there is nothing beneath the large reception hall and the dining room. However, the layout of the lower level or basement mirrors the rest of the floor plan above. The Nazi elite and dignitaries would never have visited this area – it was used for service staff, guards, and storage (including refrigeration). Today, it remains of limited historical importance and is off-limits to the general public (although some tours may offer access).

The Eagle’s Nest featured a heating system (underfloor, in the case of the main reception room), which needed to be activated up to two days in advance during the colder months. Electrical power to the entire facility was supplied by an underground cable from Obersalzberg, supplemented by a MAN submarine diesel engine and an electrical generator installed in an underground chamber near the main entrance. This backup power system, not accessible to visitors, has never been required in an emergency.

The original elevator winch and mechanisms were not replaced until 1972. The ornate ‘gold’ elevator cabin was reserved for Hitler and other elite. Beneath it, a bland grey service cabin was used to transport guards, goods, and supplies to the basement level. An additional safety measure included an emergency elevator capable of carrying three people, powered by a separate engine and accessible from the lower service cabin. Like the backup generator, this emergency elevator has never been needed.

Outside, where visitors can enjoy breakfast, lunch, and the pleasures of a ubiquitous German beer garden depending on the time of day, there is a path (the Mannlsteig trail) leading further up the hill. This offers the vantage point from which many photos of the Eagle’s Nest are taken. From here, it’s possible to wander around the narrow summit, taking in the views and the majesty of nature. There are also walking paths for hikers that lead to various destinations off the historically proverbial beaten track.

There are steps at the front of the Eagle’s Nest, descending in front of the main reception hall, which soon towers over the visitor. Here, a difficult trail winds all the way down to the parking area of the bus terminus. Of course, it is much quicker, easier and safer to take the elevator down – which is exactly what Hitler did on each infrequent visit he made, although he was reportedly concerned that the mechanism would fail or that the winch motor would be struck by lightning.

As it happened, Hitler was never struck by the hand of God and even survived several assassination attempts at the less supernatural hand of man. However, he left countless tens of millions dead and even more suffering in his wake.

This is precisely why the Eagle’s Nest stands as a complex symbol of the Nazi era. Its preservation serves as a physical ‘brick and mortar’ reminder of the Third Reich’s power and how a perverse ideology held the world hostage and on the brink of destruction. Visiting the Eagle’s Nest is not just a trip through history; it is an immersion into the tragic legacy of a bygone era, set against the backdrop of one of Europe’s most stunning landscapes. As such, it is an unparalleled experience.

Delve Deeper

Your chance to learn more about this ww2stories.org story by delving deeper!

Capture timeline

The Obersalzberg and the broader Berchtesgaden area were liberated on 4 May 1945 without serious incident by the 3rd Division of the US XV Corps, as the SS had fled and scattered earlier. Although the task of taking Berchtesgaden was initially assigned to the US XXI Corps, changing circumstances and expediency led the 3rd Division to go in first.

Following their efforts, Berchtesgaden was assigned to Major General Milburn’s XXI Corps sector just as the war in Europe officially ended (7-8 May 1945). On 9 May, Colonel Vance Batchelor, Corps G-2 (Divisional Intelligence), dispatched a Task Force to Berchtesgaden to secure specific sites and gather information about the life led by the Nazi hierarchy there.

Irrespective of whether a small group of French soldiers reached the Eagle’s Nest on 4 May 1945 or not (circumstantial evidence does exist), by 10 May, the Americans had certainly taken possession. A US Army report titled ‘Hitler’s Mountain Retreat’ by the Headquarters XXI Corps, Office of the Assistant Army Chief of Staff, dated 28 May 1945, was released later that same month.

What did the Americans think?

US XXI Corps report details their impressions of the main reception hall as American troops inspected the Eagle’s Nest:

“The room itself, with its windows cut through the six-foot walls, was the last word in luxuriously finished accoutrements. In all, it contained 18 large upholstered chairs, three wicker deck chairs with pads and pillows, six marble topped tables, one radio and one combination radio-phonograph.

The automatic selection buttons of the radio did not include London, although the panel did indicate that the Führer could get the BBC and even New York, if he cared to turn the dials. The places for which there were automatic selection buttons were Konigsburg, Breslau, Hamburg, Berlin, Leipzig, Munich, Koln, Stuttgart and Deutschland Sender [a long-wave radio broadcasting service with nationwide coverage used extensively for propaganda purposes by Nazis].

Hitler’s study and lounge which adjoined the dining hall in the rear was simply decorated with dark stained wainscoting. It was rather dark and sombre, light coming in from only one side.

The lodge was conspicuous for its absence of books and recreational facilities. Other than the radios, phonograph and scenery there were none. Several large pads of expensive sketching paper were found in the living room, which were probably there for the convenience of Hitler’s once frustrated aspirations.

Everything was new, brand new, and even the furniture gave the appearance of having just come from the manufacturer. It looked as though it needed living and the warmth that human living could give it.”

What was it like to work at the Eagle’s Nest?

Interestingly, the US XXI Corps report details Obersalzberg workers sharing their strong opinions about their Nazi masters with the US Task Force interpreters. In a section ironically titled ‘Just One Happy Family’, the report states:

“Most of them spoke of Hitler with obvious reverence in their voices but two ‘Stammerbeiter’, or regular employees, characterised him along with Himmler and Bormann as ‘mean’.

They declared that when Hitler flew into a rage he would chew on a rug or anything he could get his teeth into and sometimes beat his dog.

George Mehr, elevator operator at the Eagle’s Nest, spoke well of Hitler and Goering but evidenced keen dislike for Bormann. He said that on several occasions Bormann telephoned to him at 2:30 o’clock in the morning to say that he and his family would ascend to the Kehlsteinhaus to see the sunrise and on each occasion failed to show up.

A telephone technician named Loder told of Bormann’s forcing Frau Bormann and the children out of their Obersalzburg house at five o’clock in the morning and forcing them to flee to Munich. He added that Bormann got along very well, however, with screen actresses whom he invited to the mountain frequently.

Loder also said that Bormann was a heavy eater and drinker. His favourite drink was cognac and he was known to lock himself up in his room for extended sprees.

After having dinner with Hitler, a strict vegetarian, Loder declared Bormann returned to his own home to gorge himself with roast goose and cognac.

Mrs. Zynchski, Goering’s housekeeper, reported that Goering disliked both Himmler and Bormann. Bormann was heard by others to declare that he ‘made’ Himmler.”

These accounts, revealing internal squabbles and blatant arrogance, reflect not only the nature of the Nazi regime but also broader human susceptibilities. The constructs we create and the boundaries we impose are often childish at their core. However, the consequences are invariably far from playful. WWII, the legacy these Nazi leaders imposed on tens of millions, stands as one of the darkest moments in global history.

We value your opinion!

Your feedback is important to us. If you enjoyed this article and would like to see similar content, show your appreciation by clicking the ‘Claps’ icon below. Also, ensure you stay up-to-date with our latest articles by subscribing to our Newsletter. You’ll receive new posts directly to your email inbox. Thank you for your support!

‘History has to be shared to be appreciated’

Subscribe to our Mailing List. We’ll keep you in the loop.

Cover photo & other photos (unless otherwise specified): Author ©