The History and Legacy of Hitler’s Berghof and the Nazi Complexes at Obersalzberg

– A ww2stories.org Exclusive –

Join Ross J. Robertson and Dr Konstantinos Giannakos as ww2stories.org takes you on an exclusive two-part series on Hitler’s Bavarian retreat. Delve into the history of the Berghof and Obersalzberg, once key Nazi sites, and discover how they compare to what remains today.

The Obersalzberg region in Bavaria, Germany, is steeped in WWII history due to its association with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi regime. Nestled in the Bavarian Alps, this picturesque area hides a dark past, where idyllic landscapes were overshadowed by the sinister activities of the Third Reich. From Hitler’s grandiose mountain retreat, the Berghof, to the labyrinthine tunnel complexes, and even the Berchtesgaden railway station, Obersalzberg was a nerve centre of Nazi power – an alternative Reich Chancellery. Today, some of these sites still stand as solemn reminders of a turbulent era. One is even a tourist attraction, but all are places of education and reflection. This two part article delves into the history and legacy of these infamous locations, comparing their wartime significance with their present-day state.

Hitler’s Berghof

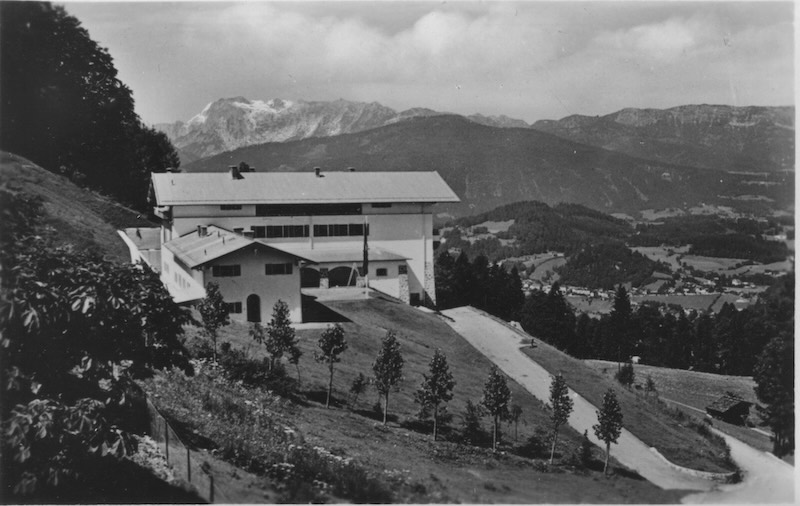

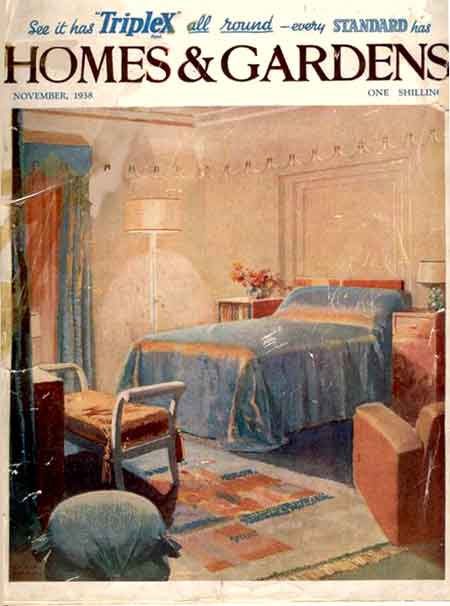

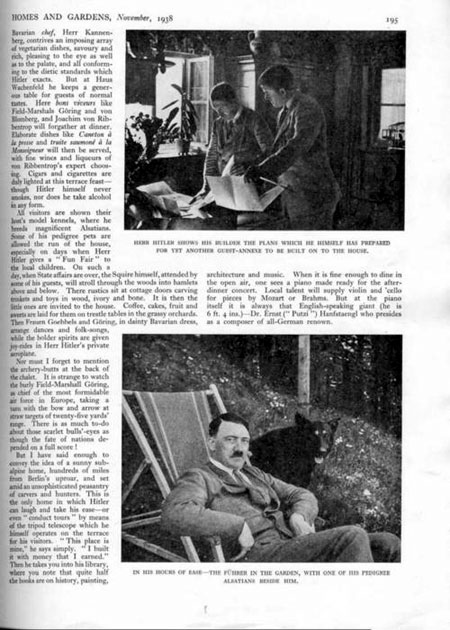

The Berghof (literally ‘mountain farmstead’ in English, but best described as an opulent ‘retreat’ or ‘chalet’), originally a modest holiday home known as Haus Wachenfeld, was purchased by Adolf Hitler in 1933. The royalties from his book Mein Kampf (My Struggle) meant that he didn’t have to struggle for very long, at least not financially. It made him a millionaire, and he allocated a large portion of these funds, along with donations from supporters, to transform the house into a grand alpine retreat. The renovation, completed in 1936, featured a spacious terrace, a grand hall with a large multi-pane panoramic window that could be fully lowered, and lavish interiors designed to impress visitors and dignitaries. Incredibly, the Berghof even appeared in a ‘puff piece’ in the November 1938 issue of the UK magazine Homes & Gardens, which is a fascinating read found in the Delve Deeper section below.

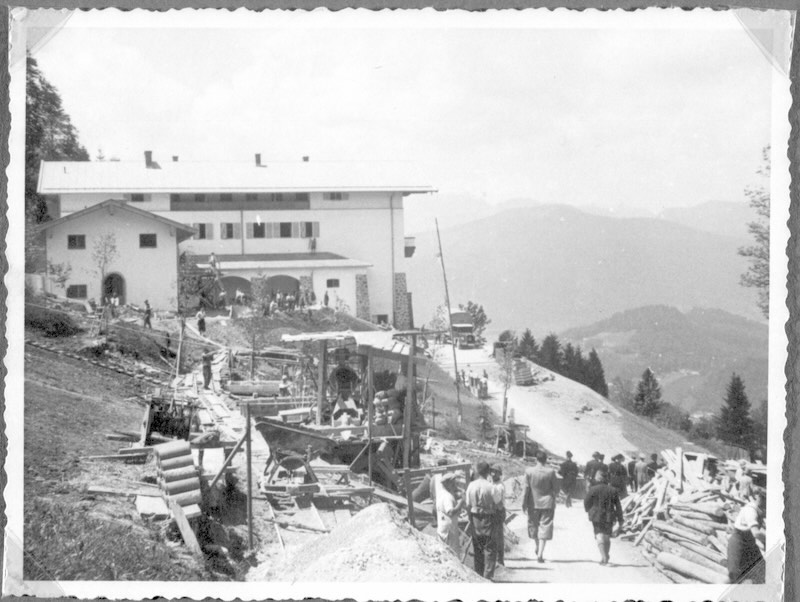

Source: Unknown

The Berghof was not just a personal retreat; it was also a strategic location which grew around it. It was part of a larger complex of Nazi buildings on the Obersalzberg, including the Kehlsteinhaus (Eagle’s Nest – for the ww2stories.org article, click here), various residences for the elite Nazi leadership, and a large SS barracks. This area became a second seat of government, where Hitler could conduct state affairs away from Berlin. The isolation from adoring fans and the security offered by the Berghof allowed Hitler to plan military strategies and host important meetings with his inner circle and foreign leaders. Notable guests included the Duke and Duchess of Windsor on 22 October 1937, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain on 15 September 1938, and Benito Mussolini on 19 January 1941.

Life at the Berghof was a blend of work and leisure. Hitler spent considerable time there, particularly during the early years of WWII. His daily routine often included afternoon briefings with military staff, followed by a late afternoon walk to the Mooslahnerkopf Teehaus (Teahouse). During these walks, Hitler would select an individual to accompany him, a gesture considered a great honour.

Evenings were typically reserved for social gatherings, which could turn into lengthy rants that often continued into the early hours. Berghof’s grand hall, with its expansive windows overlooking the Alps, and the terrace served as the backdrop for many photographs of Hitler, as well as propaganda films.

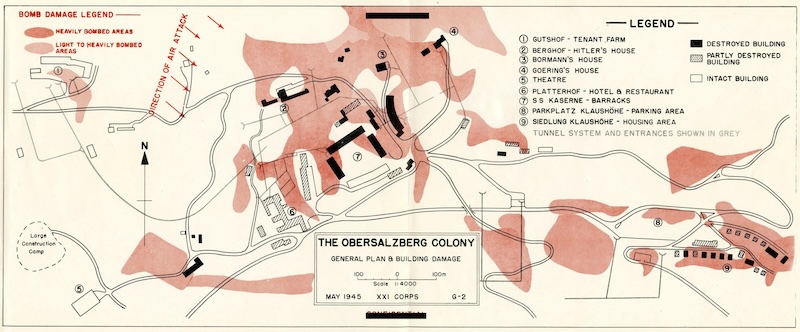

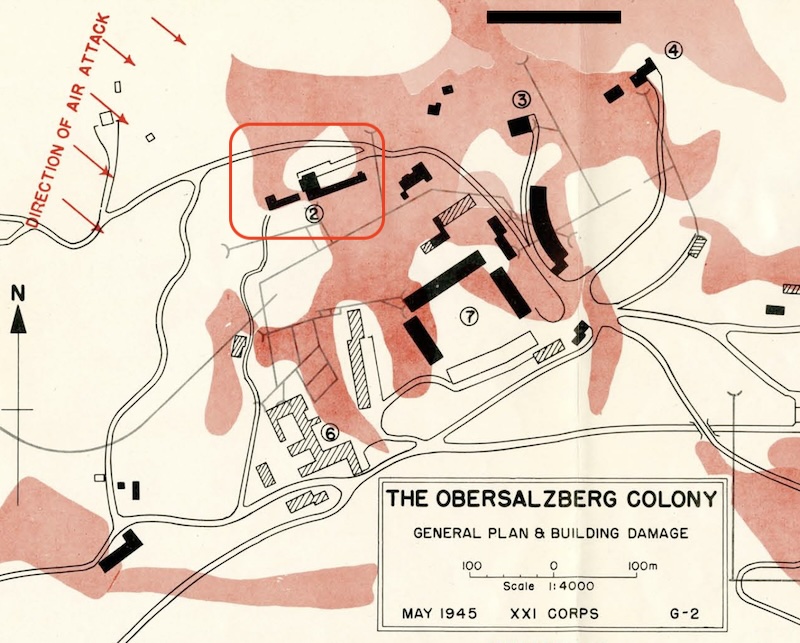

Bombing the Berghof

As the Allies closed in on Nazi Germany, fears grew that Hitler’s inner circle and fanatical SS forces might regroup for a final, desperate stand in the Bavarian Alps. Although Hitler was trapped in his Berlin bunker, the Allies pressed on toward Berchtesgaden, his mountain stronghold. On 25 April 1945, more than 300 Lancasters under RAF Bomber Command, including those from No. 460 Squadron RAAF, along with 16 Mosquitos and over 270 American B-24 Liberators, took to the skies for a dramatic raid on the Berchtesgaden railway system and the Obersalzberg.

Flying under clear blue skies, the bomber crews marvelled at the breathtaking beauty of the Alps below, until the peace was shattered as they closed in on their target. Thick clouds and snow cover obscured the area, including the Eagle’s Nest, as they unleashed over 1,400 tons of bombs, including four massive 12,000-pound Tallboys, designed to obliterate Nazi bunkers beneath the complex.

Göring, the only one in residence at the time, and Bormann’s houses were utterly destroyed. The SS barracks lay in ruins, and the Berghof, Hitler’s private retreat, was severely damaged. Although the tunnel systems remained intact, the raid dealt a decisive blow to any Nazi hopes of holding out in the mountains. Days later, American and French forces arrived to sift through the shattered remains.

What the US Troops Discovered at the Berghof

As American troops advanced into the Obersalzberg region at the very end of the war, they were greeted by the remnants of Hitler’s notorious retreat: the Berghof. The area was liberated on 4 May 1945, without serious incident by the 3rd Division of the US XV Corps, as the SS had fled and scattered earlier. Although the task of taking Berchtesgaden was initially assigned to the US XXI Corps, changing circumstances and expediency led the 3rd Division to go in first. French forces, specifically the 2nd Armoured Division, were also in the area at the time.

Following their efforts, Berchtesgaden was assigned to Major General Milburn’s XXI Corps sector just as the war in Europe officially ended on 7-8 May 1945. On 9 May, Colonel Vance Batchelor, Corps G-2 (Divisional Intelligence), dispatched a task force to Berchtesgaden to secure specific sites, including Kehlsteinhaus (the Eagle’s Nest) and gather information about the life led by the Nazi hierarchy there. By 10 May, the Americans had firmly consolidated the entire area. A US Army report titled ‘Hitler’s Mountain Retreat’ by the Headquarters XXI Corps, Office of the Assistant Army Chief of Staff, dated 28 May 1945 describes the Berghof as they found it.

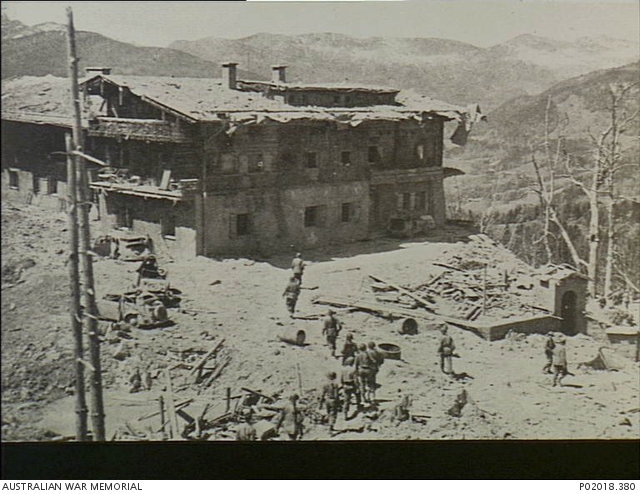

Source: AWM©

According to the report, “The Berghof, as Hitler’s Obersalzberg house was called, was all but completely destroyed.” The aftermath of a devastating 25 April 1945 RAF aerial bombardment left the structure in ruins. However, even more damage had been inflicted by the SS, who set fire to the remains after meticulously looting the site to prevent anything of value from falling into Allied hands.

The main room, which measured approximately 45 x 70 feet (14 x 21 m), stood as an empty black shell. Describing the scene, the report stated, “The 17 x 25 foot (5.2 x 7.6 m) window in front of which Hitler delighted in having himself photographed was scattered in innumerable broken and melted pieces of plate glass.” Among the debris lay the twisted springs of upholstered chairs and remnants of several radios that had succumbed to the flames. Despite the devastation, the mantle of the 10 foot (3 m) red marble fireplace remained intact, albeit white and broken, evidence of the intense heat that had warped the grates in the firebox.

The exploration continued to the second floor, which was likely Hitler’s bedroom. This room, in a state of complete disarray, was identifiable only by its size. Surrounding it were smaller rooms filled with simple iron beds, “twisted by the heat into fantastic shapes.” The left wing of the house bore the brunt of the attack, leaving “nothing but dust, brick, and boards.” Here were the apartments of Hitler’s entourage, with those at the west end, which had sustained less damage, providing a glimpse of the simple yet comfortable design.

Venturing further into the basement, the American troops discovered supply and storage rooms, along with equipment necessary for functionality such as water boilers. A passageway led down a long flight of stairs to Hitler’s shelter tunnel, which featured another opening near the house itself.

Göring’s and Bormann’s residences were also largely destroyed in the air attack. While Bormann’s house was said to be lavish, Göring’s, with the exception of his wife’s room, was relatively simple. However, it was filled with “rare and valuable bric-a-brac collected from across Europe.”

The report also highlighted the extensive security presence in the area. The SS Kaserne, or barracks, had grown from housing a mere 100 men before the war to accommodating up to 500 by its end. “There was also a contingent of 50 SS women in the barracks, who, together with other women who worked there, provided companionship at the orgies reported to have gone on there by all workers on the mountain. Food and drink for the elite SS was apparently plentiful.”

As the German armies collapsed, the Nazis resorted to desperate measures, bringing in about 200 women to operate smoke machines positioned along the roads. These machines were intended to conceal the mountain sanctuary, but “the idea did not work out because aerial destruction of Nazi transport prevented the continuous supply of the necessary chemicals.”

The report also highlights the stark contrasts between the extravagant lives of the Nazi elite and the grim realities faced by those who laboured to support them, particularly in construction projects: “All of this Obersalzberg life was predicated on and made possible by the sweat, toil, and misery of hundreds of Poles, Czechs, Slovaks, and Russians. These individuals were herded into a camp of wretched shanties at the end of each day’s forced labour.”

While this was certainly true of the tunnel and bunker system under Obersalzberg, as well as numerous other projects throughout occupied Europe, the pre-war construction of both the Berghof and Eagle’s Nest was contracted to German companies, employing workers and specialists such as stone masons from across the Reich and beyond.

The Berghof Today

Today, virtually nothing remains of the Berghof. The site has been cleared, and nature has reclaimed much of the area, leaving only the retaining wall and some scant foundations visible. The beginning of the driveway off the main road is distinguishable, but little else. Following the RAF air attack on 25 April 1945 that left the area in ruins, the Bavarian government demolished the burned shell of the Berghof in 1952 to prevent it from becoming a neo-Nazi shrine. The area now serves as a place of reflection and education, with the Documentation Center Obersalzberg nearby, providing historical context and exhibits about the Nazi era.

In contrast, the nearby former Hotel zum Türken, which was repurposed during the war to house the Reichssicherheitsdienst (Reich Security Service; RSD – Hitler’s bodyguard) personnel who patrolled the grounds of the Berghof, was repaired in 1950 and still stands today. Its stone sentry box where RSD guards stood is prominently located at the corner. However, the building has recently been closed to the public, denying access to the tunnels below that used to connect directly to Hitler and Eva Braun’s quarters.

Source: RJR (Author)©

Uncover more about ‘Hitler’s Paradise’ and the sinister history hidden within the picturesque alpine area of Obersalzberg and the town of Berchtesgaden in Part II, coming soon on ww2stories.org.

Delve Deeper

Your chance to learn more about this ww2stories.org story by delving deeper!

Source: US National Archives.

If you believe that political optics and image management are recent phenomena, think again. More than 80 years ago, under the direction of Dr. Goebbels, Minister of Propaganda, Hitler carefully crafted his image as a serious statesman whose demanding role required an environment of rest and recuperation. In its November 1938 issue, the UK magazine ‘Homes & Gardens’ featured an article that was less about showcasing Hitler’s Berghof retreat and more about shaping his image outside Germany. Given the dramatic political events of 1938, it was a calculated strategy to bolster his political persona on the global stage.

HOMES & GARDENS

Magazine Transcript:

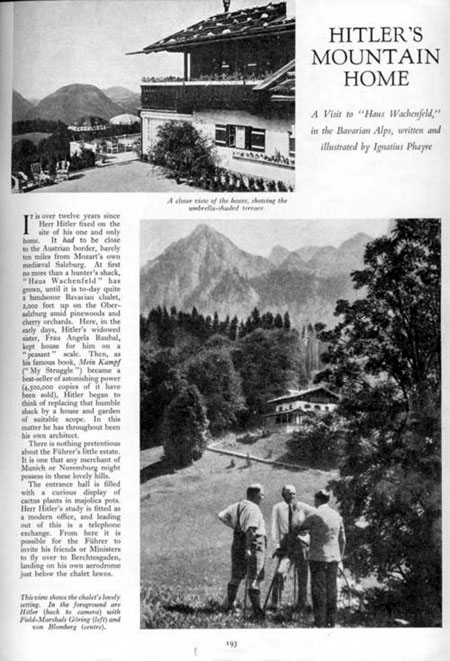

‘Hitler’s Mountain home, a visit to ‘Haus Wachenfeld’ in the Bavarian Alps, written and illustrated by Ignatius Phayre.’

“It is over twelve years since Herr Hitler fixed on the site of his one and only home. It had to be close to the Austrian border, barely ten miles from Mozart’s own mediaeval Salzburg. At first no more than a hunter’s shack, ‘Haus Wachenfeld’ has grown until it is to-day quite a handsome Bavarian chalet, 2,000 feet up on the Obersalzberg amid pinewoods and cherry orchards. Here, in the early days, Hitler’s widowed sister, Frau Angela Raufal, kept house for him on a ‘peasant’ scale. Then, as his famous book Mein Kampf (‘My Struggle’) became a best-seller of astonishing power (4,500,000 copies of it have been sold), Hitler began to think of replacing that humble shack by a house and garden of suitable scope. In this matter he has throughout been his own architect.

There is nothing pretentious about the Führer’s little estate. It is one that any merchant of Munich or Nuremberg might possess in these lovely hills.

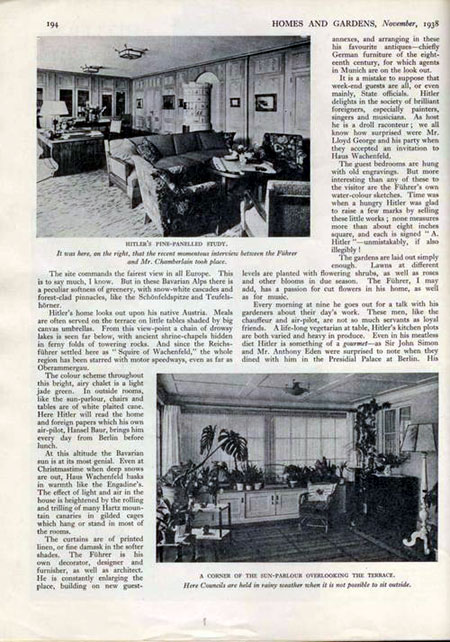

The entrance hall is filled with a curious display of cactus plants in majolica pots. Herr Hitler’s study is fitted as a modern office, and leading out of this is a telephone exchange. From here it is possible for the Führer to invite friends or Ministers to fly over to Berchtesgaden, landing on his own aerodrome just below the chalet lawns.

The site commands the fairest view of all Europe. This is to say much, I know. But in these Bavarian Alps there is a softness of greenery, with snow-white cascades and forest-clad pinnacles, like the Schönfeldapitae and Tuefelshörmer.

Hitler’s home looks out upon his native Austria. Meals are often served on the terrace on little tables shaded by big canvas umbrellas. From this viewpoint a chain of drowsy lakes is seen far below, with ancient shrine-chapels hidden in ferny folds of towering rocks. And since the Reichsführer settled here as ‘Squire of Wachenfeld’ the whole region has been starred with motor speedways, even as far as Oberammergau.

The colour scheme throughout this bright, airy chalet is light jade green. In outside rooms, like the sun-parlour, chairs and tables are of white, plaited cane. Here Hitler will read the home and foreign papers which his own air pilot, Hansel Baur, brings him every day from Berlin before lunch.

At this altitude, the Bavarian sun is at its most genial. Even at Christmastime when deep snows are out, Haus Wachenfeld basks in warmth like the Engadine’s. The effect of light and air in the house is heightened by the rolling and trilling of many Hartz mountain canaries in gilded cages which hang or stand in most of the rooms.

The curtains are of printed linen or fine damask in the softer shades. The Führer is his own decorator, designer and furnisher, as well as architect. He is constantly enlarging the place, building on new guest annexes, and arranging in these his favourite antiques – chiefly German furniture of the eighteenth century, for which agents in Munich are on the lookout.

It is a mistake to guess that week-end guests are all, or even mainly, State officials. Hitler delights in the society of brilliant foreigners, especially painters, musicians and singers. As host, he is a droll raconteur; we all know how surprised were Mr. Lloyd George and his party when they accepted an invitation to Haus Wachenfeld.

The guest bedrooms are hung with old engravings. But more interesting than any of these to the visitor are the Führer’s own water-colour sketches. Time was when a hungry Hitler was glad to raise a few marks by selling these little works; none measures more than about eight inches square, and each is signed “A. Hitler” – unmistakably, if also illegibly!

The gardens are laid out simply enough. Lawns at different levels are planted with flowering shrubs as well as roses and other blooms in due season. The Führer, I may add, has a passion about cut flowers in his home, as well as for music.

Every morning at nine he goes out for a talk with the gardeners about their day’s work. These men, like the chauffeur and air-pilot, are not so much servants as loyal friends. A life-long vegetarian at table, Hitler’s kitchen plots are both varied and heavy on produce. Even in his meatless diet, Hitler is something of a gourmet – as Sir John Simon and Mr. Anthony Eden were surprised to note when they dined with him at the Presidential Palace at Berlin. His Bavarian chef Herr Kannenberg, contrives an imposing array of vegetarian dishes, savoury and rich, pleasing to the eye as well as to the palate, and all conforming to the dietetic standards which Hitler exacts. But at Haus Wachenfeld he keeps a generous table for guests of normal tastes. Here bons viveurs like Field Marshals Göring and von Blomberg, and Joachim von Ribbentrop will gather at dinner. Elaborate dishes like Caneton à la presse and truite saumoné à la Monseigneur will then be served, with fine wines and liqueurs of von Ribbentrop’s expert choosing. Cigars and cigarettes are duly lit at this terrace feast – though Hitler himself never smokes, nor does he take alcohol in any form.

All visitors are shown their host’s model kennels, where he breeds magnificent Alsatians. Some of his pedigree pets are allowed the run of the house, especially on days when Herr Hitler gives a ‘Fun Fair’ to the local children. On such a day, when State affairs are over, the Squire himself, attended by some of his guests, will stroll through the woods into hamlets above and below. There rustics sit at cottage doors carving trinkets and toys in wood, ivory, and bone. It is then the little ones are invited to the house. Coffee, cakes, fruits, and sweets are laid for them on trestle tables in the grassy orchards. Then Frauen Goebbels and Göring, in dainty Bavarian dress, perform dances and folk-songs, while the bolder spirits are given joy-rides in Herr Hitler’s private aeroplane.

Nor must I forget to mention the archery-butts at the back of the chalet. It is strange to watch the burly Field-Marshall Göring, as chief of the most formidable air force in Europe, taking a turn with the bow and arrow at straw targets of twenty-five yards range. There is as much to-do about those scarlet bulls’-eyes as though the fate of nations depended on a full score.

But I have said enough to convey the idea of a sunny sub-alpine home, hundreds of miles from Berlin’s uproar, and set amid an unsophisticated peasantry of carvers and hunters. This is the only home in which Hitler can laugh and take his ease – or even ‘conduct tours’ by means of the tripod telescope which he himself operates on the terrace for his visitors. “This place is mine,” he says simply. “I built it with money that I earned.” Then he takes you into his library, where you note that quite half the books are on history, painting, architecture, and music. When it is fine enough to dine in the open air, one sees a piano made ready for the after-dinner concert. Local talent will supply violin and cello for pieces by Mozart or Brahms. But at the piano itself it is always that English-speaking giant (he is 6 ft. 4 ins.) – Dr. Ernst (‘Putzi’) Hanfstaengl who presides as a composer of all-German renown.”

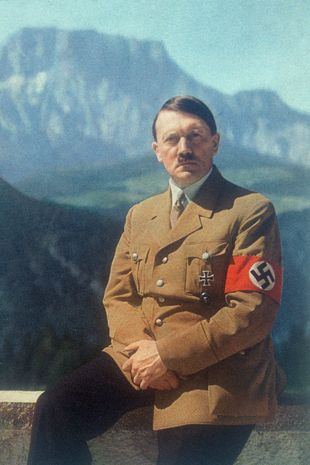

Portrayed very much as a Renaissance man – emphasising even his vegetarianism, anti-smoking stance, and teetotalism (all of which were true: Germany, under his rule, became the first European nation to ban smoking on public transport in 1941) – the article was unmistakably a propaganda tool.

However, if you ever find yourself visiting Berchtesgaden and the Obersalzberg, with their fairy-tale Hansel and Gretel-style houses set against breathtaking alpine scenery, you may begin to understand why Hitler saw the area as his personal paradise. Regardless of who you are, or what you believe yourself to be, the region’s allure is powerfully undeniable.

Footnotes

- Berghof Sign

“You are at the centre of the former Führer’s restricted area. In 1928, Hitler rented a small country house here, which he purchased in 1933. By 1936, it was expanded into the grandiose Berghof. The Berghof was damaged in a British air raid on April 25, 1945, and set on fire by the SS a few days later. In 1952, the US military government ordered the ruins to be blown up. The only fragment preserved today is the retaining wall on the southern slope.

The Obersalzberg was not only Hitler’s private country retreat but also served as the second centre of power of the German Reich, alongside the official capital, Berlin. Hitler spent more than a third of his time in power here. Important political discussions and negotiations were conducted, and decisive decisions were made, leading to the catastrophes of World War II and the Holocaust, causing the deaths of millions.” ↩︎

We value your opinion!

Your feedback is important to us. If you enjoyed this article and would like to see similar content, show your appreciation by clicking the ‘Claps’ icon below. Also, ensure you stay up-to-date with our latest articles by subscribing to our Newsletter. You’ll receive new posts directly to your email inbox. Thank you for your support!

‘History has to be shared to be appreciated’

Subscribe to our Mailing List. We’ll keep you in the loop.

Cover image: Source: US Army Photo