Was there an EAM/ELAS Communist plot to forcibly seize power in Greece after the October 1944 Liberation?

– A ww2stories.org Exclusive –

Eight decades ago, shots rang out in the centre of Athens, igniting a powder keg of political strife and all-out Civil War. Was it a communist plot or a simple misunderstanding? Uncover the truth with Dr Kostas Giannakos and Ross J. Robertson as they investigate the events that shaped Greece’s fate for years to come.

December 2024 marks the 80th anniversary of the Battle of Athens, known to posterity as Dekemvriana (the December Events). What exactly happened that December remains shrouded in controversy, with both sides – as they are after so many years – blaming each other for instigating the shootings in Syntagma Square in central Athens. Both sides also blame each other for pursuing a secret agenda for sidelining or neutralising the other. The Left in particular blames the British in general and Churchill in particular, as responsible for masterminding the whole conflict, in order to impose their geopolitical designs for the post-war world order on the Greeks.

The truth is that, despite exhaustive studies of relevant archives and personal memoirs, no one can say with certainty who initiated the shootings on 3 December 1944. Unless new evidence comes to light, we may never know for sure. The question that remains is whether there was a communist plot to forcibly seize power – not only in Athens but throughout Greece – and whether the leaders of EAM/ELAS (the communist National Liberation Front and its military arm, the Greek People’s Liberation Army) used the events in Syntagma Square as a pretext to activate a preexisting plan. This article aims to demonstrate that such was indeed the case.

Major Brian Edevrain Dillon, MBE, was an SOE (Special Operations Executive) officer deployed in Roumeli since 1943 as commander of Lillian Station. This brought him into contact with various ELAS bands and leaders. He was one of the first to enter liberated Athens in October 1944, together with Andreas Mountrichas (nom de guerre Orestis), Kapetanios (i.e. political leader) of the 2nd ELAS Division. They visited the acting military governor of Athens, appointed by the government-in-exile, Major General Panagiotis Spiliotopoulos. The purpose of their visit was to arrange the smooth transition of power, the preservation of peace and order in the capital and the delineation of areas of responsibility between the various resistance groups, in expectation of the arrival of the Greek government and the accompanying British troops.

According to Dillon, the meeting did not go well, mainly due to Spiliotopoulos’ arrogance and intransigence as he refused to recognise Mountrichas’ authority and rank. Be that as it may, an uneasy peace was more or less maintained until the arrival of the Papandreou government on 18th October 1944. On the same day, the prime minister, in a moving ceremony, raised the Greek flag on the Acropolis and then addressed the crowd that had filled Syntagma Square from the balcony of the Ministry of Finance.

The crowd, which often interrupted him with slogans in favour of EAM and the Greek Communist Party (KKE), greeted his announcements with shouts calling for a people’s republic. Papandreou, who had been forced to constantly navigate between the Left and the Right, responded with the characteristic phrase that has gone down in history: “We also believe in a people’s republic.”

However, the joy and festivities marking the liberation lasted only fifty-three days. On 3rd December, the sound of gunfire echoed once again through the streets of the capital, beginning at Syntagma Square.

In his interview for the Imperial War Museum (IWM) archive, Dillon said that, through an informant who belonged to EAM’s Central Committee, he was informed that an attack (even providing the exact date) was planned against the government by EAM/ELAS. The signal for the commencement of the operation would be the ringing of church bells. He immediately went to Lieutenant General Ronald Scobie, who commanded both the British troops in Greece, as well as the Greek regular and guerrilla forces. He reported the information, but Scobie did not believe him and told him that he was exaggerating and that he should take leave, as he was tired.

In his protests, Scobie replied that, in any case, the British had a squadron of Sherman tanks in the capital and that these were more than enough to maintain order. Dillon somewhat irreverently retorted: “General, the Germans had two armoured divisions and they could not subdue them. You’re not going to scare them.”

Dillon admitted that the Dekemvriana did not begin as he had been informed and that he did not know who fired the first shots. He stated that he thought it possible that KKE militants who were among the protesters fired against the police and gendarmes in order to provoke a violent reaction. The Communists wished the security forces to inflict casualties on the civilian population so they could use this as a pretext for launching their attack.

The interesting fact is that, as a member of the SOE, he did not belong to any organised military section. During the fighting in Athens, he stayed in an apartment and held telephone and in-person discussions with his EAM/ELAS contacts without being influenced or disturbed by anyone. His main task was to mediate between the belligerents, arrange matters concerning the distribution of humanitarian aid to the civilian population, and report the current situation to his superiors. Through his contacts, he also communicated with RAF personnel captured by ELAS. 1

Although the historiography of the Battle of Athens centres on the British troops and the Greek 3rd Mountain Brigade, it is interesting to examine the fate of the first National Guard (Ethnofylaki) battalions, which had been hastily organised only a few days prior to the fighting. It is outside the scope of this article to detail and analyse the creation and deployment of these units, but suffice it to say that their establishment was one of the first acts passed by the government after its arrival in Athens.

The battalions were intended to serve as a stopgap measure until the creation of a regular Hellenic Army and were composed of reservists from the draft class of 1936.

During the December fighting in Athens and the surrounding areas, it became apparent that the National Guard (NG) units could not function effectively. 2 According to the Hellenic Army’s official history (GES/DIS) regarding the formation of NG Battalions, the Attica National Guard Regional Command included, among others, the 102nd and 103rd NG Battalions, based in Koropi and Megara respectively. It is noted that both were “dissolved by the communists on 30-11-44”, prior to the outbreak of hostilities.

The 104th, 105th, and 106th NG Battalions, located in Thebes, Chalkida, and Amfissa respectively, were dissolved on 3rd December, as were the vast majority of the remaining units. The remaining NG Battalions, with the exception of the 101st NG Battalion in Athens, were dissolved in the days that followed.

In Patras, the 108th NG Battalion was garrisoned in the old barracks of the 12th Infantry Regiment, alongside other ELAS units. On 3rd December, the 1st Company relocated to two requisitioned buildings in the city centre. According to the company commander’s report, written on 10th December, most of the company’s personnel were considered ‘ethnikophrones’ (of sound national beliefs). However, approximately 30% were identified as communists, including the company’s executive officer (XO), two platoon leaders, and the first sergeant, all of whom had previously served with ELAS.

Once the company moved into its new billets, it was placed on alert as EAM had organised rallies and protests in the city. Throughout the day, the communist soldiers exhibited suspicious behaviour, attempting to make contact with EAM supporters. The company’s XO and first sergeant repeatedly left their billet under various pretexts to meet with demonstrators. Other platoon leaders reported to the company commander that communist soldiers in their platoons were behaving suspiciously, and that they lacked confidence in the loyalty and reliability of their troops.

During the night of 3rd to 4th December, communist soldiers and NCOs attempted to leave the billets and join ELAS detachments. The first sergeant had even arranged for communist sentries to be on duty to facilitate their defection. According to the commander’s report, the plot was thwarted thanks to his decisive action, implemented with the support of loyal officers and enlisted personnel. The following morning, the company was transported to the British forces’ camp in the city using British military vehicles.

On the other side of Patras, where the Battalion HQ and the other companies were billeted, the situation unfolded in a completely different way. According to the report submitted by the 4th Company commander, on the afternoon of 3rd December, the Battalion’s sentries were replaced by ELAS soldiers at the request of the Kapetanios of the 12th ELAS Regiment. This was done under the pretext that his troops used different passwords which they did not want to share with the guardsmen. An attempt was also made to allay their fears by telling them there was no need to be on guard, as ELAS had “the best intentions” towards them.

However, the commander observed that, throughout the afternoon, ELAS fighters – moving in small groups of two or three – were evacuating the barracks with their weapons and taking up fighting positions on the hill opposite the camp. By the evening, the Battalion was effectively trapped in its barracks, as ELAS had positioned machine guns to cover the exits and forbade anyone from leaving the premises. Patrols were also roaming the surrounding area, completing the blockade.

When the company commander suggested contacting the British forces stationed in the city to request aid and lift the blockade, the Battalion’s executive officer (XO) initially appeared to agree. He left, ostensibly to make contact with the British, but returned shortly after, claiming that ELAS officers had assured him there was no cause for concern. 3

Later that night, when two soldiers attempted to sneak out and establish contact with the British forces, they were stopped by the XO. The situation worsened when, during the night, the company commander was awakened by two mutinous soldiers, who took him prisoner at gunpoint. Among the mutineers was an officer from his own company.

The mutineers, who had joined ELAS, did not mistreat the prisoners but led them out of the city to the Saravali area, located south-southwest of Patras. From there, the company commander eventually managed to escape.

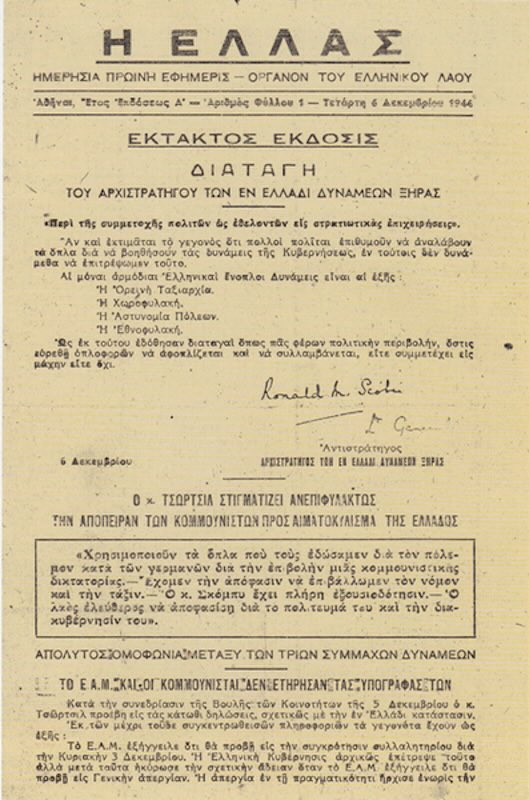

Source: 'ΕΛΛΑΣ' newspaper, 1944

From these episodes, the lack of countermeasures, the erosion and the political unreliability of the National Guard Battalions in the event of a possible EAM/ELAS coup become apparent. The government might have assigned officers and other ranks in the NG units, but it could not rely on their intervention in case of emergency. The mere fact of the bloodless and rather easy dissolution of the Battalion and the whole attempt by ELAS to reassure the National Guardsmen automatically raises important questions.

As is well known, the events in Athens began on the morning of 3 December 1944, while the next day (4 December) saw the funerals of the victims and the general strike. The fighting in Athens started at 16:00 hrs on 4 December, but only reached full intensity from the early hours of 5 December onwards. EAM claimed that there was no plan to take power by force, but was forced to engage in the Battle of Athens and the rest of the country because of the government’s intransigence and perfidy.

However, this assertion contradicts what the above-mentioned company commanders described in their reports, which they submitted on 10 and 6 December respectively, i.e. while the fighting was raging in Athens and the situation was desperate for the government forces. The whole operation of disarming the unit and its immediate implementation indicates prior planning and readiness to put it into effect on the orders of the higher ELAS command.

It is difficult to accept that all actions in Patras were carried out on the initiative of the local ELAS commander, who was improvising in reaction to political developments. Besides, if the local ELAS was reacting on the basis of what was known from the events in Athens, any actions to disarm the National Guard would logically have to take place after the beginning or during the fighting in Athens and not before. The attempts to contact the ELAS cells in the Battalion with the officers in the city or in the barracks as soon as the unit was placed on alert, raises suspicions of prior consultation on the appropriate course of action when circumstances dictated.

Throughout the day of 3 December, we see that the EAM/ELAS in Patras was mobilising, while instead the only measures taken by the government forces were to put themselves on alert and send a single company to the centre of the city, where it was operating cut off from any assistance. How unprepared the government forces were can be seen from the fact that they continued to remain in the barracks with the ELAS forces, while they agreed to replace their own sentries, ceding control of the camp to the latter. Nor did they react when they noticed ELAS men withdrawing with their weapons in small groups and taking up fighting positions on the hill opposite the camp, from where they could control it with firearms.

Based on what took place, it is likely that the government side was taken by surprise and did not know how to react. If there was a secret master plan by the government for an armed confrontation with EAM, then if anything it would have taken care to give every possible warning to its units in the provinces. They would have alerted them for any eventuality, or ordered them to take preventive action. The ease with which the 108 NG Battalion was disarmed and disbanded was certainly assisted by the weakness displayed by the unit’s command group and the lack of communication and trust between the battalion’s CO and XO, as is clearly shown by their submitted reports. 4

The assessment that the entire ELAS action was pre-planned is further strengthened by the similar events that took place in Pyrgos and the comparable fate that befell the local 109 NG Battalion. According to the report submitted on 4 December by the 3rd Company’s CO, Captain Stefanos Papanikos, the company had been formed on 27 November and had a total strength of 249 officers and ORs. On 1 December, it received clothing and arms for 150 men, which were distributed the following day. After the distribution of the arms and clothing, a number of men were discharged, while others were reassigned to the 4th Company, reducing the company’s strength to 175 men, of whom 25 were supernumeraries. Papanikos stressed in his report that during the battalion’s formation, no vetting was conducted regarding the men’s political affiliations; they were inducted according to the provided orders.

On 3 December at noon, the company paraded before the Prefect, the local British military commander, the 109 NG Battalion’s CO, the commander of the local ELAS unit, and other local officials. After the parade, the company returned to barracks, and Papanikos was invited to attend a luncheon hosted by the British commander. The atmosphere was very cordial, with compliments and speeches of mutual confidence exchanged between the English, ELAS, and the Prefect. However, while the meal was in progress, the ELAS representatives began leaving gradually, and within 15 minutes, all of them had left, which raised concerns. Papanikos requested and received permission to return to his company, even asking for an escort of British soldiers. The British Lieutenant-Colonel replied that there was no cause for alarm, as the commander of the ELAS battalion had given his word of honour that he would not take any action against the National Guard, for whom he professed cordial feelings.

Papanikos returned to his company, where he personally supervised security measures and instructed the officers on duty to remain alert for any suspicious movements. He then proceeded to battalion headquarters to receive instructions. There, he met the CO and the Prefect and asked them for information about the current situation. After some time, the Company’s Duty Officer (CDO) arrived and informed him that suspicious ELAS movements had been observed. He also reported that a platoon leader, formerly an ELAS officer, had ordered his platoon to assemble at the barracks.

At about 19:00 hrs, when Papanikos and the CDO set out to return to the camp, they were stopped by an ELAS patrol and escorted back. Upon arrival, they found that the guards had been replaced by ELAS personnel, and the entire block was surrounded by men armed with machine guns and other heavy weapons.

When Papanikos entered his office, he encountered an ELAS officer accompanied by 15 armed men. When ordered to evacuate the camp, the ELAS officer replied that ELAS did not recognise the government and that the maintenance of law and order was now its responsibility. He also informed Papanikos that the National Guard was being abolished, and its men would be incorporated into ELAS. The captain and his troops were given the option to join them, or else his command would be disbanded. Papanikos, after reiterating his order for the ELAS officer to leave, informed him that he would report the matter to his CO and the British Battalion CO. He then instructed the CDO and his men to disregard the ELAS officer’s orders until his return.

Papanikos sought out the Prefect and the Greek and British commanders to analyse the situation with them. He requested British soldiers to help him regain control of the unit, but the British commander refused, suggesting instead that his men use their rifles without ammunition. Papanikos argued that this was impractical and would inevitably lead to an exchange of fire. The CO of the 109 NG Battalion and the Prefect also pressed the British for assistance or at least permission to use their weapons, but the British officer ordered them to take no action and wait for the arrival of ELAS officers, whom he planned to order to disperse.

After about an hour, the ELAS representatives arrived and held private conversations with the British officer. Following this, the British commander ordered Papanikos to return to the camp, determine the quantity of arms removed by the ELAS forces, and report back. Papanikos complied and found no soldiers from his company remaining at the camp – only ELAS personnel, who were loading the company’s armament onto vehicles. He reported these facts to the British commander and again requested British soldiers to stop the ELAS forces. The British refused and summoned the ELAS commander for another private conversation. Subsequently, the British officer ordered all NG Bn officers to relocate to the British camp, where they spent the night. As Papanikos noted in his report, apart from the arms, the ELASites removed the company’s clothing and food, as well as the officers’ luggage.

The events leading to the disarmament of the Battalion’s 4th Company unfolded in a similar manner, according to the report of its CO. The difference was that the company had been formed on 1 December from the other companies’ excess personnel. It had not had time to form into platoons and had experienced discipline problems between former ELASites and other soldiers. The company’s provisional commander, Lieutenant Mentzidakis, had reported that he was unable to impose his authority on his men and had requested to be transferred to another company.

On the afternoon of 3 December, the company commander, who had reported for duty just the previous day, was ordered by the battalion CO to organise a platoon of guards, which was to remain in the camp. The problem was that his men received rations in cash and left the camp to eat with their families, while very few had uniforms. The captain did as ordered and even replaced the BDO, who was a former ELAS officer. However, even in this case, the sentries were disarmed without bloodshed by other ELASites who were part of the company’s roster, while other ELAS units had surrounded the camp with heavy weapons. What followed was the usual procedure of looting the company’s armament and other materials.

If one conclusion is to be drawn from Papanikos’ report, it is that ELAS had made every effort to deceive the political and military authorities as to its real aims, while the British were also taken unawares and did not know how to react. For its part, ELAS planned and enforced a fait accompli, in a masterly manner and without causing bloodshed. It is obvious from all the descriptions that the way things turned out, any resistance by the NG would have been futile and would have ended in a bloodbath. ELAS could well have carried out acts of violence and executions against the guardsmen after their disarmament, especially those belonging to opposing resistance groups, but it deliberately avoided doing so. The most logical explanations are that its officers had no instructions to do so, or that they did not want to provoke the intervention of British troops. Besides, everything depended on the outcome of the battle for Athens. If ELAS succeeded in seizing power in Athens and established its rule over the country, it would have had all the time it needed to deal with its opponents.

The reaction of the British commander was typical of his ignorance of the real intentions of ELAS, since he thought that the whole action of disarming the National Guard was the product of a misunderstanding, believing that it would be resolved as soon as he spoke privately with the local ELAS commander, who had given him his “word of honour” for the sincerity of his intentions. He then chose not to escalate the conflict but let things develop, ceding the initiative to ELAS, presumably awaiting further instructions from his command. He was not prepared to risk the lives of his soldiers in a Greek affair without clear orders or a direct threat to their lives. 6

The first 14 NG battalions that had managed to be formed by the beginning of Dekemvriana were disbanded by ELAS, and many of their members defected with their weapons to its forces, increasing its firepower. Meanwhile, only the cadres of three battalions in the capital area remained loyal to the government. Thus, on 7 December 1944, the formation of new NG battalions began on the grounds of the old palace, present-day Parliament and Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, with the call-up of reservists of the 1932–1939 classes, who lived in areas not occupied by ELAS or had taken refuge in areas controlled by the government and British troops. In this way, on 9 December, the 141 NG Battalion had been formed, with personnel mainly from the gendarmes and the 142 TE with personnel mainly from the “X” organisation.

The problem with their creation was that the necessary materials were in warehouses in the west of Athens and had to be transported through areas controlled by ELAS. For this purpose, convoys of vehicles were organised, accompanied by British tanks and infantry for protection. Eventually, the ELAS forces managed to cut off their supply, but the government forces had acquired enough materiel to create new battalions. On 20 December, the government and the British activated a second militia recruitment centre in the Piraeus area, and the first to be formed was the 160 NG Battalion. The formation of the NG battalions proceeded according to the areas liberated by government forces, so that, from 7 December 1944 to 6 January 1945, 36 units were formed at the rate of one battalion per day. Their staffing with team and platoon leaders largely consisted of cadets from the Military Academy (Evelpidon), after its evacuation on 11 December. Reinforcements for the defending government forces during the first days of December were provided by the 22nd Special Battalion, which had been transferred from the Middle East and renamed the 144 NG Battalion.

During Dekemvriana, the NG battalions undertook mainly military rather than police tasks, for which they were conceived. Their main missions were of the “Clear and Hold” type in areas cleared of ELAS troops by the British, a role for which they were best suited. Each unit and later NG brigade was attached to a respective British unit, which it supported during clearing operations. Thus, the 5th National Guard Brigade was placed under the command of the 28th British Brigade, and its battalions were attached as follows: 146 NG Battalion to 2/4 Hampshire Battalion, 152 NG Battalion to the 2nd Somerset Light Infantry (SLI) Battalion, and the 156 NG Battalion to the 2nd King’s Liverpool Battalion. The British forces loaned or donated whatever equipment they could spare, while the units themselves used whatever material they could scrounge from other sources.

The Army’s official history mentions a rate of formation of two NG battalions per day following the liberation of populous districts such as Nea Smyrni, Kallithea, Harokopou, and Nea Sfageia, which collectively yielded a total of 20,000 men. The officers (both career and reservists) residing in Athens formed the pool of cadres for the command of the units, with very satisfactory results. It is also noted that a surplus of officers, who could not be assigned to staff the units, formed separate ones and fought as ordinary soldiers – a sign of the fanaticism and tension of those days.

The actions taken during Dekemvriana marked a turning point in Greece’s volatile history. With the National Guard battalions disbanded and many defecting to ELAS, the political landscape shifted dramatically. The British, caught in a web of uncertainty, failed to intervene decisively, and the stage was set for a new, turbulent chapter in the Greek Civil War, where no side could be trusted and the struggle for power would consume the nation for years to come.

Note: According to the official British history, part of the 4th Indian Infantry Division was deployed in the Peloponnese. During autumn 1944, the division was operating in the Italian Theatre of Operations, seeing extensive action in efforts to breach the Gothic Line. Relieved from the front in early October 1944, instead of the anticipated period of rest and refit, it was sent directly to Greece.

The 7th Indian Infantry Brigade was deployed to Macedonia, arriving there on 12 November 1944. The 5th Indian Infantry Brigade was sent to Athens, landing on 17 November 1944, while the 11th Indian Infantry Brigade was dispatched to the Peloponnese, also arriving on 17 November 1944, with its headquarters in Patras.

The 11th Brigade was commanded by acting BGen Henry Cecil John Hunt, Baron Hunt, KG, CBE, DSO (22 June 1910 – 7 November 1998), an officer best known as the leader of the successful 1953 British expedition to Mount Everest. The brigade comprised the 2nd Bn/Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders, the 2nd Bn/7th Gurkha Rifles, and the 3rd Bn/12th Frontier Force Regiment, along with support elements.

We value your opinion!

Your feedback is important to us. If you enjoyed this article and would like to see similar content, show your appreciation by clicking the ‘Claps’ icon below. Also, ensure you stay up-to-date with our latest articles by subscribing to our Newsletter. You’ll receive new posts directly to your email inbox. Thank you for your support!

‘History has to be shared to be appreciated’

It’s FREE! Subscribe to our Mailing List. We’ll keep you in the loop.

Cover photo: The ELAS Flag. Courtesy Chris Goss ©

Footnotes

- According to Menelaos Charalambidis (p. 63), on 1st December 1944, the EAM leadership, as soon as it was informed about Scobie’s decision to disarm the various resistance groups, ordered ELAS A’ Corps (Athens Area) to implement ELAS’ Contingency Plan for the capture of Athens. The author, on page 72, mentions that the rally of 3rd December was not directly related to the military confrontation option, but its aim was political. He also notes that ELAS had such a plan, drafted in large part by Theodoros Makrides (nom de guerre “Ektoras”), the most significant and savvy ELAS staff officer. Makrides was a pre-war career officer who had been dishonourably discharged following the failed 1935 Venizelist coup. The plan addressed the capture of Athens following the German withdrawal and the subduing of the city’s quisling and/or anti-communist armed bands. EAM’s leadership did not clarify to their subordinates whether they should take immediate action against the British troops and, during the crucial first 48 hours, issued conflicting orders concerning the commencement of the attack, followed by countermanding them. In any case, it seems that EAM–ELAS was prepared for the confrontation that followed and was merely waiting for the right pretext. Thus, Dillon was partly correct in his assessments.

↩︎ - According to Sotiris Rizas (p. 66), the ELAS leader Aris Velouchiotis, on 28th November 1944, urged his fighters from the 1936 draft class to join the National Guard. Earlier, on 24th November, the KKE leader George Siantos had asked Aris to encourage such a stance among the ELAS guerrillas. Indicative of the tensions and the climate of mutual suspicion prevalent at the time was his order for the fighters to hand over their weapons before joining the NG. Similarly, the men who belonged to the Militia (Ethniki Politofylaki, the EAM Police) were instructed to take their weapons and ammunition and rejoin ELAS after handing over their duties to the NG units.

↩︎ - The British Battalion in Patras at the time of Dekemvriana was the 2nd Battalion/Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders. This is according to Richard Bromley-Gardner’s IWM narrative (Reel 3). Bromley-Gardner was an officer with the 2nd Battalion Highland Light Infantry (HLI). His battalion was flown to Araxos from Italy in October, then moved to Patras, where they were replaced by the Cameronians in November and moved to Athens, where they participated in the fighting.

↩︎ - During the Dekemvriana, the battalion’s command group (CO, XO, Ops Officer, etc.) submitted reports describing their version of the events that led to the unit’s disbandment. In these reports, they attempted to shift the blame onto anyone but themselves. It is evident that the unit lacked any semblance of esprit de corps; morale and discipline were nonexistent, and leadership was clearly deficient. The creation of a capable, combat-worthy, and reliable Hellenic Army had, indeed, a very long way to go.

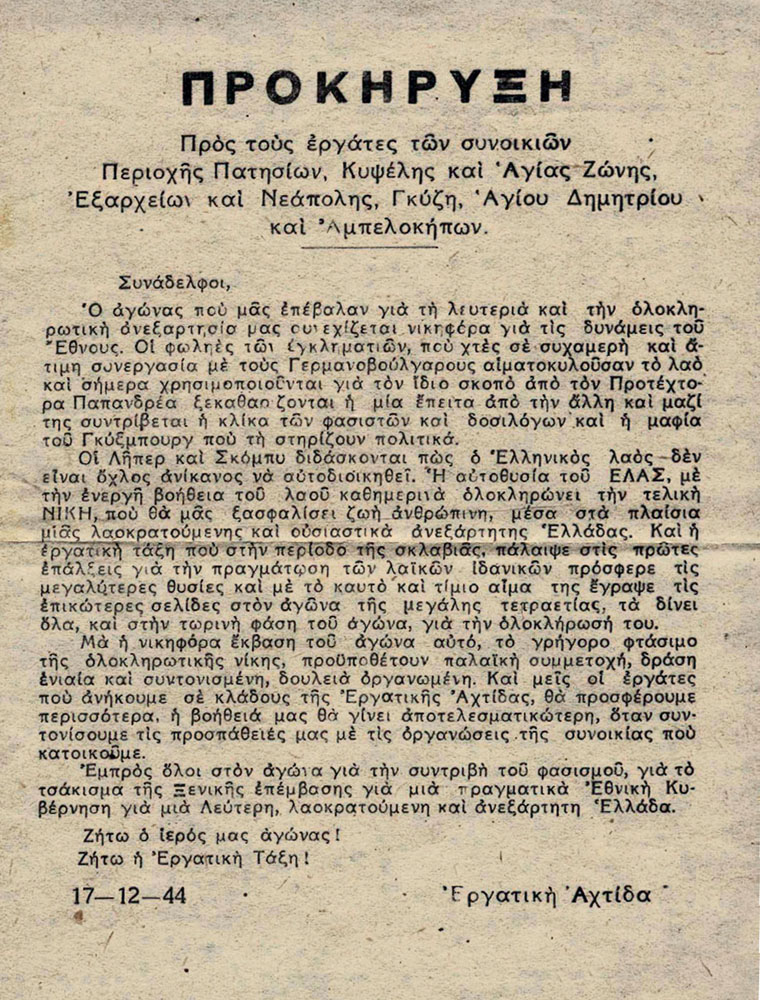

↩︎ - Pamphlet translation:

PROCLAMATION

To the workers of the neighbourhoods of the Patissia, Kypseli, and Agia Zoni, Exarchia, and Neapoli, Gyzi, Agios Dimitrios, and Ampelokipoi.

Colleagues,

The struggle imposed on us for freedom and the complete liberation of our homeland continues victoriously for the forces of the Nation. The dens of traitors, which yesterday, in shameful and dishonourable collaboration with the German-Bulgarians, shed the blood of the people, are now being used for the same purpose by the puppet Papandreou, and one after another, they are being demolished along with the clique of fascists and collaborators and the Gang of Gyziburgh who politically supports them.

Liber and Scobie are being taught that the Greek people are not a crowd incapable of self-government. The self-sacrifice of ELAS, with the active assistance of the people every day, completes the final VICTORY that will secure us Human Life, within the framework of a people-controlled and genuinely independent Greece. And the working class that fought in the first lines for the realisation of the popular ideals in the struggle against slavery, now, in the current phase of the struggle for its completion, offers the greatest sacrifices and, with its hot and honourable blood, writes the most epic pages in the struggle of the great four-year period, giving everything for the current phase of the struggle for its completion.

But the victorious outcome of this struggle, the rapid achievement of total victory, requires popular participation, unified and coordinated action, and organised work. And we workers who belong to branches of the Workers’ League will contribute more; our help will be more effective when we coordinate our efforts with the neighbourhood organisations in which we live.

Forward, everyone, in the struggle for the crushing of fascism, for the breaking of foreign intervention, for a dramatically National Government, for a Free, People-controlled, and independent Greece.

Long live our Sacred Struggle!

Long live the Working Class!

17-12-44

Workers’ League

↩︎ - According to the CO of the 3rd National Guard Brigade, in a report dated 20th January 1945, the effort to reconstitute the NG battalions in Patras and Pyrgos met with strong objections from the local EAM. The British Brigadier, seeking to maintain peace in both cities, recommended and succeeded in suspending the decision. Later in the month, the remaining force of the 109 NG Battalion, consisting of the unit’s officers and 70 ORs, arrived in Patras from Pyrgos. These were amalgamated with the Patras Battalion to form a composite battalion consisting of two companies, from which all leftists were purged. This force was billeted with the British, who tried to help in any way they could, but the guardsmen faced appalling conditions, lacking personal items, medicines, bedding, and even foodstuffs, while at the same time having exhausted all available funds.

↩︎

Select Bibliography – Webpages

* Αρχείο ΓΕΣ/ΔΙΣ, 1492/Γ/12, Ονομαστική Κατάσταση του 108 Τάγματος Εθνοφυλακής της 25/12/1944 με τους Παρουσιασθέντες Εφέδρους Οπλίτες στο Τάγμα

[Hellenic Army Archives (GES/DIS), 1492/G/12, 108 National Guard Battalion List of Personnel, dated 25/11/1944, containing the Reserve Enlisted Personnel which Reported for Duty]

* Αρχείο ΓΕΣ/ΔΙΣ, 1492/Γ/21, Έκθεση του 4ου Λόχου του Τάγματος Εθνοφυλακής Πατρών της 10/12/1944 για τα Συμβάντα της 03 – 04/12/1944

(GES/DIS, 1492/G/21, Report by 4th Company/Patras National Guard Battalion, dated 10/12/1944, describing the Events of 03-04/12/1944)

Αρχείο ΓΕΣ/ΔΙΣ, 1492/Γ/22, Έκθεση του 1ου Λόχου του Τάγματος Εθνοφυλακής Πατρών της 10/12/1944 για τα Συμβάντα της 03 – 04/12/1944

* (GES/DIS, 1492/G/22, Report by 1st Company/Patras National Guard Battalion, dated 10/12/1944, describing the Events of 03-04/12/1944)

Αρχείο ΓΕΣ/ΔΙΣ, 1492/Δ/6, Έκθεση του 3ου Λόχου του 109 Τάγματος Εθνοφυλακής Πύργου της 04/12/1944 για τον Αφοπλισμό του Λόχου από τον ΕΛΑΣ

[GES/DIS, 1492/D/6, Report by 3rd Company/109 National Guard Battalion (Pyrgos), dated 4/12/1944, describing the Company’s Disarmament by ELAS]

* Αρχείο ΓΕΣ/ΔΙΣ, 1492/Δ/7, Έκθεση του 4ου Λόχου του 109 Τάγματος Εθνοφυλακής Πύργου της 06/12/1944 για την Παραλαβή του Λόχου και τον Αφοπλισμό του από τον ΕΛΑΣ

[GES/DIS, 1492/D/7, Report by 4th Company/109 National Guard Battalion (Pyrgos), dated 6/12/1944, describing the Company’s Formation and Subsequent Disarmament by ELAS]

* ΓΕΣ/ΔΙΣ, Αρχεία Εμφυλίου Πολέμου, Τόμος 1, Αθήνα, 1998

(GES/DIS, Civil War Archives, Vol. I, Athens, 1998)

* ΓΕΣ/ΔΙΣ, Η Απελευθέρωσις της Ελλάδος και τα Μετά Ταύτην Γεγονότα (Ιούλιος 1944 – Δεκέμβριος 1945), Αθήνα, 1973.

[GES/DIS, The Liberation of Greece and the Subsequent Events (July 1944 – December 1945), Athens, 1973]

* Ριζάς, Σωτήρης, Απ’ την Απελευθέρωση στον Εμφύλιο, Καστανιώτη, Αθήνα, 2011

(Rizas, Sotiris, From Liberation to Civil War, Kastaniotis, Athens, 2011)

* Τσακαλώτος, Θρασύβουλος, 40 Χρόνια Στρατιώτης της Ελλάδας: Πώς Εκερδίσαμε τους Αγώνας μας, 1940 – 1949, Τόμοι Α΄ και Β΄, Ακρόπολη, Αθήνα, 1960

(Tsakalotos, Thrasyvoulos, 40 Years a Soldier of Greece: How we Won our Struggles, 1940 – 1949, Vol. I & II, Acropolis, Athens, 1960)

* Χαραλαμπίδης, Μενέλαος, Δεκεμβριανά 1944 – Η Μάχη της Αθήνας, Αλεξάνδρεια, Αθήνα, 2014

(Charalambidis, Menelaos, Dekemvriana 1944 – The Battle for Athens, Alexandria, Athens, 2014)

* National Archives, WO 202/892, Instructions for the Formation of the GNA, Appendix 1 Outline of the Events Leading up to the Start of the Formation of the National Army

* Imperial War Museums (IWM), Sound Archives, Dillon, Brian Edevrain, 23787/2002, Reel 8, accessible at http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80022012, την 01 December 2024

* https://www.britishmilitaryhistory.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/124/2020/09/4-Indian-Division-Greece-1944-45.pdf, 16 December 2024

* https://greekreporter.com/2024/10/12/athens-liberated-nazi-occupation/, 16 December 2024

* https://www.britishmilitaryhistory.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/124/2020/09/Chronology-of-Key-Events-Greece-1944-1948.pdf, 16 December 2024

* https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80011646, 16 December 2024

* https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80010411, 16 December 2024