A personal view by Gav Don

Part I of II

This article also appears on the HMS Triumph Association website.

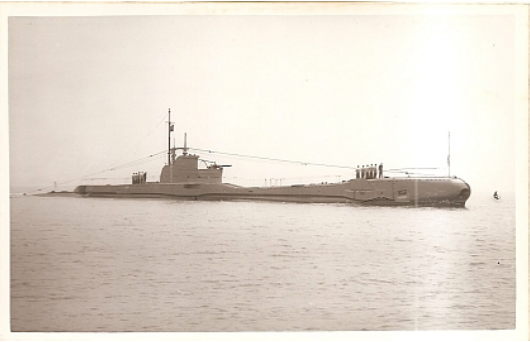

Discovered by shipwreck hunter extraordinaire Kostas Thoctarides in 2023 after a 25-year quest, the June 2023 revelation of HMS Triumph in the Aegean grabbed global attention. Join former Royal Navy officer Gav Don as he explores its fateful final day.

With the spectacular discovery of her wreck by Kostas Thoctarides (see ww2stories.org article here), we can now make some reasonably strong deductions of what happened on Triumph’s last day.

Of course, at the end of the day, doubt remains, but the range of possibilities is quite small, small enough anyway to write this narrative of likely events.

Triumph’s wreck is not the only evidence we have. I have spent over a decade studying Mediterranean submarine operations (there are many memoirs, reports, analyses and histories) and I’ve used this bank of knowledge to fill in the gaps. We also have the positions and headings of three torpedoes lying on the seabed near Sounio, and the positions of the minefields, as data points.

What follows is a very sad story, indeed an upsetting one for the descendants of Triumph’s crew. Sadly, there is no way of stepping around the sadness, but while the events are a shock, knowing what happened may also be a comfort.

So, let’s go on.

Setting the scene

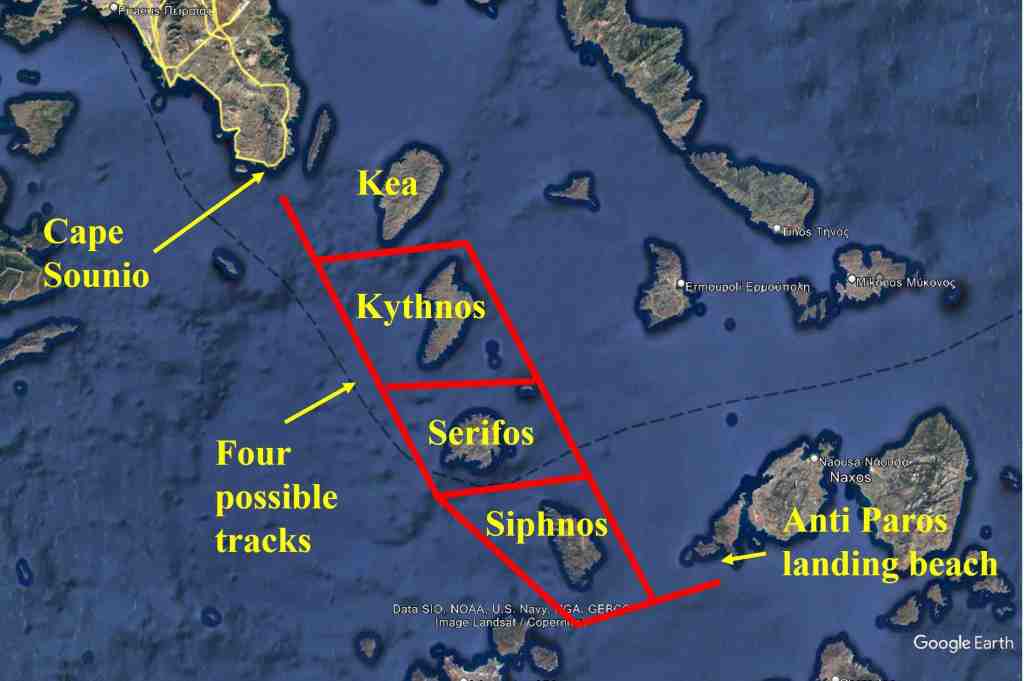

Perhaps the best way to start is with a map.

This shows the centre of the Aegean Sea. At top left is Cape Sounio, with its Temple of Poseidon. At bottom right is Antiparos. Here were waiting some 35 escaped soldiers from Operation ‘Lustreforce’, the army of some 50,000 men landed to protect Greece from German invasion. Almost as soon as they landed, Lustreforce had found 400,000 heavily armed Germans pouring over the Greek border towards them. In the pell mell retreat that followed, about 10,000 men of Lustreforce were captured. Some of these escaped, and another 2,000 or so evaded capture and were wandering Greece looking for some way home to Egypt.

Triumph’s orders were to approach the beach at Antiparos on the night of 9/10th January, pick up all the men waiting there, and sail them home to Alexandria.

We know (from the Kriegsmarine War Diary, captured and translated after the war) that a submarine carried out a torpedo attack on a barge being towed by the tug Taxiarchis round Cape Sounio on 9th January 1942.

We also know, from our own submarine history, that the only submarine tasked to operate in those waters that day was Triumph. It is 100% certain that it was Triumph which carried out that attack.

So, we find Triumph off Cape Sounio on the morning of the 9th January, with orders to be at the beach at Antiparos at some point in the middle of the night of 9/10th.

The Antiparos beach pickup

But at what time? Probably around midnight, for three reasons.

First, Triumph would need to allow herself time to make a quiet and cautious approach to the beach from the open water to the south, well after dark, creeping in on the surface on her (silent) electric motors. Her gun’s crew would be closed up ready for action. On her bridge, men would be searching for the coded torchlight signal from the beach that all was safe. Triumph would have started her run towards the beach at about three miles off – within easy visual range – searching all around in case the landing had been compromised and had become a trap.

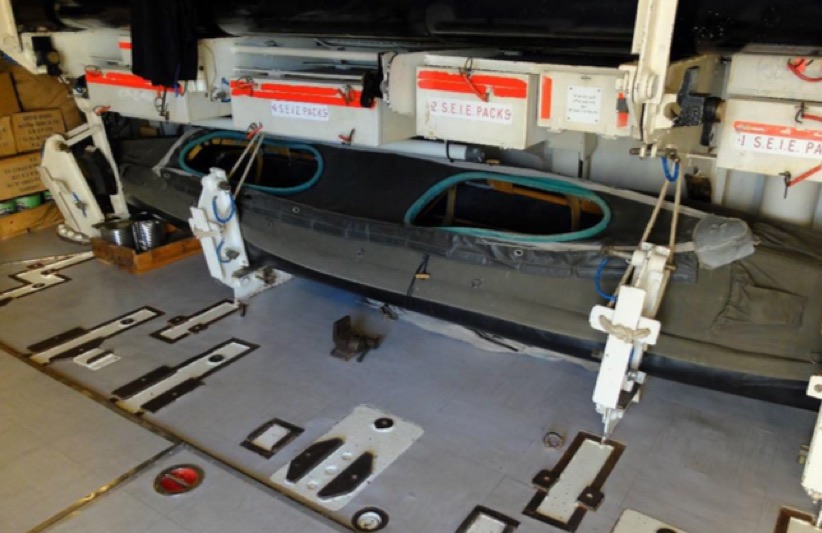

At about a mile from the beach, she would have reduced speed to a walking pace and brought her folding canvas canoes onto the casing until, at 200 yards from the beach, she would have stopped and lowered the canoes into the water, manned by her two embarked commandos and Lt (Lieutenant) Robert Don, who served as her beach officer.

Overall, her approach to the beach would take the best part of an hour. It could not begin until well after the end of Marine Twilight, which was at about 19:00 hrs local time that day.

We know that moonrise was at 00:30 hrs on the 10th January. Triumph would have wanted to make her approach before moonrise in case of ambush, but would have wanted to use the light of that night’s half-moon to help get the escape party into their boats on the beach and out to her – it was very hard to see a submarine on the surface in starlight, so the rowers and paddlers might easily have got lost on the way.

I think it is likely that Triumph’s plan was to be 200 yards (183 m) off the beach by midnight, to give Lt Robert Don and the Commandos 30 minutes to paddle ashore, marshal the escapers and to assess what other boats and helpers were available.

By the time this was all done, the moon would be over the horizon and the beach party would then then get around 35 men in groups of one, two, or three out to the submarine in the light of the half-moon, well before pre-dawn twilight arrived at about 04:30 hrs.

It would probably have taken 2 or 2.5 hours to ferry the escapers out to the boat, and the operation would have been completed by about 03:00 hrs. Photograph 2 (below) depicts the type of canoe used.

With her escapers aboard, Triumph would then have 90 minutes of darkness in which to retire southwards, start main engines at 03:30 hrs, proceed southwards at ten knots until 04:30 hrs for one more hour’s battery charge, feed the escapers a hot meal, and then dive for the first leg of the transit home.

If she arrived at the beach later than midnight, she might run out of night to clear the beach. If she arrived much earlier, she would have to transfer the escapers in full darkness and risk men going astray.

The journey south to Antiparos

With those deductions made, we can work back along Triumph’s probable planned track from her patrol position off Sounio to the beach at Antiparos with some confidence.

A glance at the map shows that she had four choices of track.

The northern track option passed between Kea and Kythnos. Two middle options passed between Kythnos and Serifos, and Serifos and Siphnos. The southern track option passed south of Siphnos.

What the map does not show is that the three northern tracks all meet a pronounced current, known as a ‘set’, heading westwards out of the central Aegean. This is in the region of 1 knot. A modern ship or submarine would not be concerned by such a slight current, but Triumph’s speed when submerged was only 3.5 knots (6.5 kph), making a 1 knot (1.8 kph) current ‘on the nose’ an issue because it cut her speed of advance by a third.

The set seems to fade to zero south of Siphnos.

A set matters even to a surfaced submarine. While Triumph’s two big diesels would propel her at a maximum speed of around 15 knots (27.8 kph) if pushed, pushing her was unwise (engines break if stressed and these had been in constant use for over a year), so her Commanding Officer (CO), Lt Johnny Huddart, would not have wanted to make more than 12 knots (22.2 kph) on the surface if possible.

In the circumstances, Triumph would have planned to use only one main engine for propulsion, using the other (clutched to the big electric motor) as a generator to pump charge into her batteries as she steamed south. With one engine working at a comfortable rate, her speed would be about 10 knots (18.5 kph).

Working back from our deduced arrival time a few miles off Antiparos at 23:00 hrs gives a track distance from there back to Sounio of 70-75 nautical miles (130-140 km). The northern tracks are a few nautical miles shorter, but have that adverse set.

The southern track offered another benefit – it needed just one course change, midway between Siphnos and the island of Kimolos to the south. The southern track also has no small islets or islands to avoid along the route. Submarine navigation was hard enough, especially at night, to make a simple track without obstacles more attractive than jinking around islands in the dark without radar.

I believe that Lt Johnny Huddart chose the southern track.

It is likely that Triumph planned to surface about an hour after sunset (by when the half-light of marine twilight had faded fully to black). Sunset on Jan 9th was at 17:51 hrs local time, so I think Triumph’s plan was to surface at 18:30 hrs, when she would be about due west of the north end of Serifos. This would put her close enough to get a reasonable visual chart fix before firing up her diesels to sail on at 10 knots while charging her batteries.

On the surface, with power now freely available the cook, Leading Chef Cornelius O’Brien would be able to cook breakfast for 19:30 hrs, and lunch for 22:00-22:30 hrs.

This passage plan would give her about 9 hours submerged at 3.5 knots (6.5 kph) – 31.5 nautical miles (58.3 km) – and 4.5 hours on the surface at 10 knots (18.5 kph) – 45 nautical miles (83.3 km) – to arrive south of Antiparos at 23:00 hrs for her run in to the beach, with a little time in hand.

By 23:00 hrs, her crew would be fed, rested, and ready for 5 hours at ‘Diving Stations’ (i.e. submarine speak for ‘Action Stations’) while she recovered the escapers.

After leaving Antiparos, she would then have a late rum ration (‘Up Spirits’) as she slipped out to sea, serve dinner around the watch change from 03:30 to 04:30 hrs, and dive by 05:00 hrs with a full battery.

To follow this plan, Triumph would have to leave the area of Cape Sounio by about 10:00 hrs, providing some ‘fat’ in the schedule between dawn and 10:00 hrs to fit in an attack before leaving, if a target presented itself.

If she was delayed (for example because of a counterattack), she could catch up on her track plan by running dived at 4.5 knots (8.3 kph) for an hour or two, as required.

So, we probably find Triumph lurking off Cape Sounio at periscope depth just after dawn on the 9th January at around 07:00 hrs, hoping that ship traffic sailing eastwards from the port of Piraeus would pass in front of her torpedoes.

Dawn off Cape Sounio

It’s time for another map.

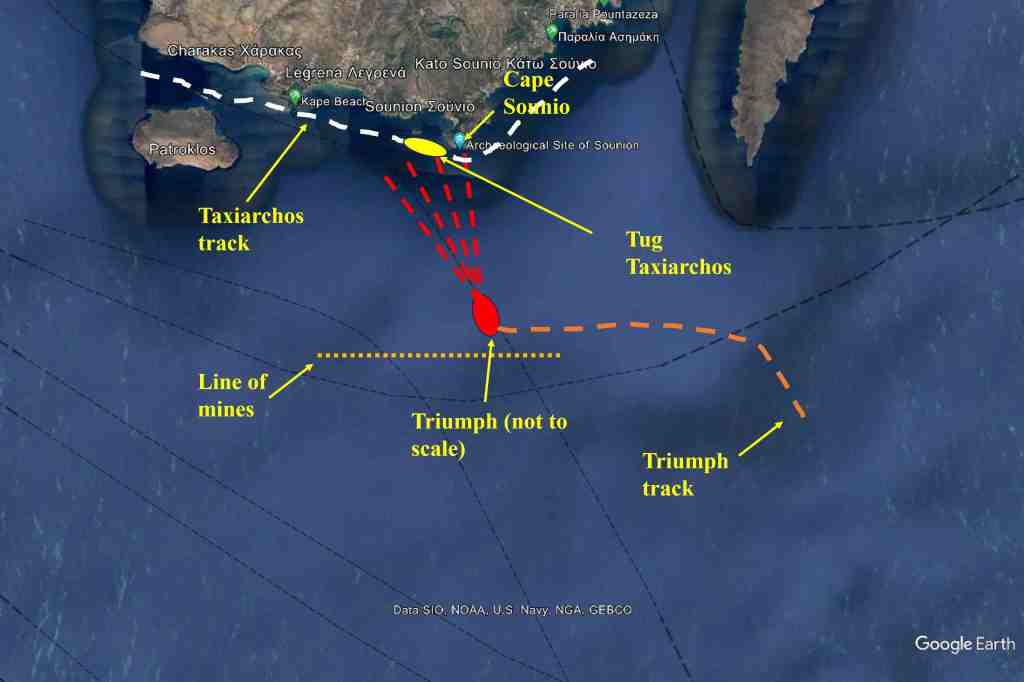

Here we see a map of Triumph’s attack. At top is Cape Sounio. The white dashed line is the track of traffic passing around the cape from Piraeus.

Traffic always kept very close inshore, no more than a few hundred metres off the rocks. This made it harder for an attacking submarine to develop a target picture (having to spot through the periscope against a shore background), allowed a ship to ground if hit but not sunk, gave shore-patrols a better chance of seeing the attacking periscope, and, of course, gave the crew less far to swim if they did sink.

Map 3 shows Taxiarchos, the yellow oval, coming round Sounio heading east at about 6 knots (11.1 kph). Triumph was probably lurking a couple of miles south of Sounio. This was at maximum torpedo range, but CO Lt Johnny Huddart might have chosen this position to extend his reach southwards, in case traffic passed further out to sea. We know she was here because of the positions of the torpedoes we have discovered on the seabed (more on that in a moment).

Just south of Triumph was a line of mines. We know from postwar records that this line comprised 120 mines laid 66 yards (60 m) apart at a depth of 39 feet (12 m), intended to sink a submerged submarine. The mines were small – only 88 pounds (40 kg) of high explosive each – but large enough to have a good chance of either sinking a dived submarine or forcing her to the surface within clear sight of the lookouts posted in concrete bunkers around Sounio’s coast. Two of these bunkers still exist. I visited one a few years ago, and there were at least three watch-bunkers about a mile or two apart around Sounio.

The minefield was laid on 6 December 1941, just a month earlier. That begs an important question. Did Triumph know they were there?

If an order to lay a field was transmitted by radio using an Enigma encoding machine, then there was a high chance that it would be intercepted in cypher at Malta and then decoded at Bletchley Park.

Malta and Alexandria, therefore, knew where many of the Italian minefields were in detail, and their positions were distributed in signals with a ‘QB’ designation, some of which have ended up in the archive at Kew. (I don’t know why ‘QB’ was chosen).

The process of acquiring a radio intercept, enciphering it, sending the enciphered intercept to Bletchley, waiting for Bletchley to crack it, and then disseminating the decrypt in a secure way back to the Mediterranean was necessarily slow.

If the mine-lay order at the start of December was sent by radio, it is quite possible, I’d say likely, that a decrypt had not reached Triumph when she left Alexandria on Boxing Day 1941.

It is also quite likely that the mine-lay order was not sent by radio at all. The Minelayer Barletta (which laid the field) was probably based in Piraeus at the time, and the order might well have originated just ten miles away in Athens, and been carried by a despatch rider.

If Triumph did not know that the field was there from a QB signal, it is likely that she saw it on her Mine-Detecting sonar Unit (MDU) when she arrived off Sounio.

We know that she was fitted with an MDU because it is referred to twice in writing, once in a patrol report and the second time by inference in a letter home from my uncle, Lt Robert Don. It was a standard fit for Batch 1 T-class submarines.

We also know that it worked, because patrol reports by other T-class boats refer to its successful use in action.

Triumph would have approached her ‘lurking’ position from somewhere between east and southeast that morning at periscope depth – the same depth as the mines. An approach from that direction would have presented the mine field at an oblique angle to Triumph as an almost continuous line of contacts – hard to miss even on a 1941 model sonar.

There is more circumstantial evidence.

The standard operating procedure after a torpedo attack was to reverse course and sail away from the firing point – the ‘datum’ – to open deep water as quickly as was consistent with remaining quiet and preserving battery power, to frustrate a counter-attack.

The firing datum was marked by a pronounced surface disturbance – the ‘splash’ caused by the pulses of water coming out of the torpedo tubes that launched the torpedoes.

The torpedoes lying on the seabed today are on a 350 degree heading, which clearly implies that Triumph fired her torpedoes while also on that track – just west of north. That would make her normal evasion route southwards.

But south from the firing datum would have taken her right across the mine- line. I believe that she knew about the mine line because she could see it on her MDU, so instead, she evaded westwards, parallel to the mine line.

Now, back to the attack.

The Taxiarchos attack

Here we have four pieces of unequivocal evidence that effectively define where Triumph was when she attacked Taxiarchos.

Three of these pieces are the three Mark VIII torpedoes lying on the seabed in a line west of Cape Sounio. The fourth is the torpedo detonation on the shoreline that was reported back to the Kriegsmarine.

We also know that the maximum run-range of a 1941 Mark VIII torpedo in 1941 was 5,000 yards – 2.5 nautical miles (4,570 m and 4.6 km respectively). We know, finally, that the seabed torpedoes lie on a roughly 350 degree track heading.

What does that add up to?

A Mark VIII torpedo ran straight on the track on which it was fired – i.e. the heading of the firing submarine. When its fuel ran out, the engine simply stopped and the torpedo sank to the seabed on that same heading. So, the track heading of the torpedoes today is the heading on which they were fired.

We can extrapolate back from the course and run distance of the four torpedoes – 5,000 yards (4,570 m) on the reciprocal course of 170 degrees – to deduce Triumph’s firing point. When we do that, we find that she fired from just inside the line of mines.

Because the seabed torpedoes are separated laterally by a few hundred metres, we can tell that Triumph fired them ‘on the swing’, i.e. while turning either to port or starboard, but more likely to starboard as Triumph tried to ‘follow’ Taxiarchos’ track from west to east, or left to right. An attack on the swing was known to be unreliable for aim, and it is not a surprise that all four torpedoes missed.

Why did Triumph not try to close the range before firing, to increase the chance of a hit?

The distances involved would have prevented her. Taxiarchos’ likely track was between the small island of Patroklos at top left (see Map 3) and the mainland, travelling at about 6 knots (11.1 kph).

Triumph, sailing in from the east at 3.5 knots (6.5 kph), would have had a limited window of opportunity to take three periscope sightings, estimate Taxiarchos’ speed and course, turn north, ready her four tubes and fire. It took the torpedoes three more minutes to run to the target. There was simply no time to close the range.

After escaping the attack, Taxiarchos passed Sounio and turned north, probably now at 8 knots. Here, she was already beyond 5,000 yards (4570 m) from Triumph and therefore out of range. To make another attack, Triumph would have had to chase her from astern, with a speed advantage of just 1 knot (1.8 kph). At that speed, Triumph would have exhausted her battery within an hour, and been forced to surface in full daylight a few miles off Cape Sounio, which would have been tantamount to suicide.

The initial attack was necessarily rushed, and it is no surprise that once the attack had failed, Triumph had to let Taxiarchos go.

After the attack

We know that an Italian aircraft was over the area at the time of the attack, and Triumph would have known that too because CO Lt Johnny Huddart would have seen it through his periscope.

What Triumph did not know was that the aircraft was unarmed. Huddart would have assumed that it was armed and should be kept at a distance, which may be another reason why she kept at extreme range from Sounio. At periscope depth, Triumph would be clearly visible to a passing aircraft as a black blob in the water.

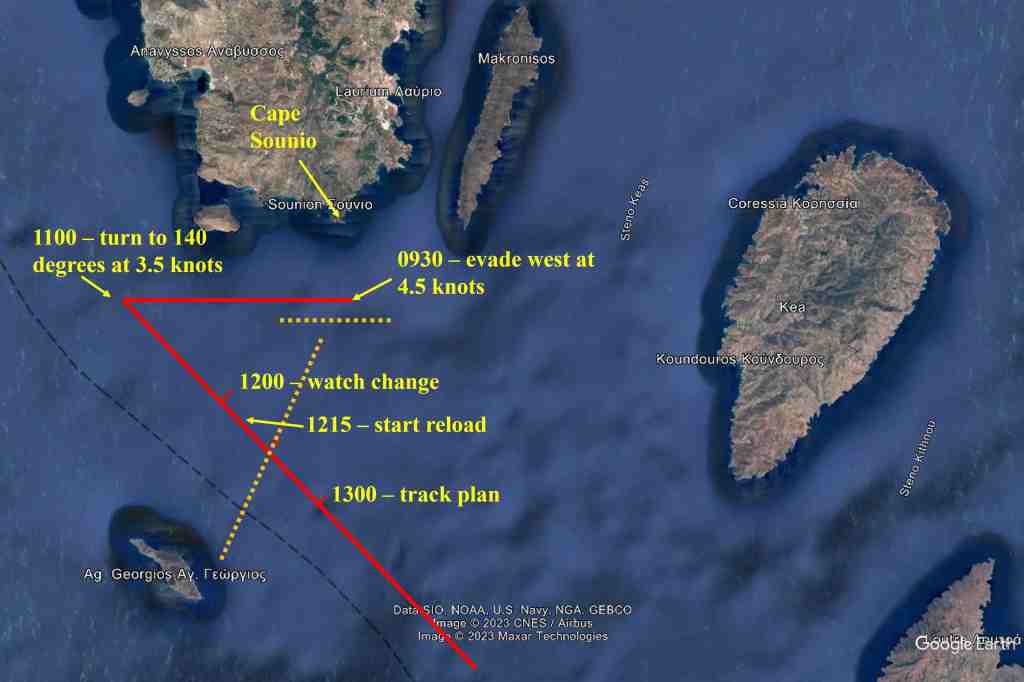

After the attack, the aircraft would have been able to see the firing splash, and Triumph would have assumed that it would close to attack within a couple of minutes. She would therefore have dived to over 80 feet (24 m) to gain concealment (she had 400 feet (122 m) of water to work in), speeded up a little to 4.5 knots (8.3 kph), and high-tailed away in the opposite direction. With the mine-line to her port side that would have to be west.

The standard procedure was to evade at speed for 30-60 minutes, to put some distance between the boat and her firing splash. An hour at 4.5 knots (8.3 kph) would take her comfortably past the mine-line. It is likely that she then slowed down (to conserve battery power) and sailed cautiously on searching for other mines on her sonar.

Time for a fourth map.

With an aircraft behind her and the likelihood that the shore-patrols and/or the aircraft would summon up high speed corvettes from the north, it is likely that Triumph made a longer and faster evasion run than average. Also, a longer evasion west would take her to water in which she might, just, encounter a new target sailing south from Piraeus.

Here the picture gets fuzzier.

If Triumph evaded on a westerly course at 4.5 knots (8.3 kph) for thirty minutes, and then further west at 3 knots (5.5 kph) for an hour, that would take her to a little southwest of that small island of Patroklos off Cape Sounio.

We can picture CO Lt Johnny Huddart and Lt Alfred Peterkin, his navigating officer, crouched over the small chart table at around 10:00 hrs in the control room with a pair of brass dividers measuring off distances. The question was, turn southeast now, or wait a bit?

Alfred would have pointed out that a little more westing would offer two advantages – the first was that the start of their track to Antiparos would benefit from a good position-fix using the island of Patroklos, clearly in sight 3.5 nautical miles (6.5 km) to their northeast, the temple of Poseidon clearly in sight to the east, and the edge of land north of Patroklos.

The second was that by starting a little further west, they would have a single course to steer to hit the gap south of Siphnos, of 140 degrees, with no need to accurately time course changes along the way. 140 degrees would take them close aboard the island of Serifos about half-way, at around sunset, giving a mid-track fix from periscope depth to eliminate the errors caused by current along the track.

I believe that the argument looked as strong to CO Lt Johnny Huddart as it looks to me, so he decided to sail another hour or so and 3 nautical miles (5.5 km) west, past Patroklos, before turning onto a 140 degree track for Siphnos.

I believe that Triumph turned onto her 140 course at about 11:00 hrs on the 9th. Sailing submerged for 8 hours at 3.5 knots (6.5 kph), she would make 28 nautical miles (51.8 km) before surfacing west of Serifos at 19:00 hrs, about 5 nautical miles (9.2 km) off, close enough to get a good fix.

Get ready for more!

Don’t miss out on the second instalment of this exclusive analysis on the HMS Triumph’s demise – coming your way next week on ww2stories.org

The Author

The dedicated curator of the HMS Triumph Association website, retired Royal Navy Officer Gav Don has invested countless hours delving into the archives in a relentless quest to unveil the fate of HMS Triumph. His personal interest has intensified this mission, as his uncle was among those on board when the submarine was tragically lost, claiming all hands. To explore further insights into his discoveries, visit the Association’s HMS Triumph 1942 website by clicking here.

Acknowledgements

ww2stories.org would like to thank Planet Blue – ROV Services for their underwater images. A leading enterprise specialising in marine projects, it was founded in 1999 by award-winning professional diver Kostas Thoctarides. It offers expert solutions such as observation, inspection, repair, maintenance, and installation support. Check out their website here.

We value your opinion!

Your feedback is important to us. If you enjoyed this article and would like to see similar content, show your appreciation by clicking the ‘Claps’ icon below. Also, ensure you stay up-to-date with our latest articles by subscribing to our Newsletter. You’ll receive new posts directly to your email inbox. Thank you for your support!

‘History has to be shared to be appreciated’

Subscribe to our newsletter. We’ll keep you in the loop.