This article first appeared on Divernet UK in December 2023, courtesy of the author.

A well-preserved wreck of a RAF Bristol Beaufighter TF Mk X off the Greek island of Naxos has been misidentified for many years. Researcher and wreck hunter enthusiast Ross J. Robertson investigates.

Splashing into the turquoise waters of the Aegean is always a joy. With a hand securing mask and regulator firmly in place, you take the plunge. There is a brief moment of weightlessness and anticipation as you roll backwards over the side. That’s followed by a shock of coolness as your back penetrates the water, and then the disorientation of being briefly suspended upside down amidst a flurry of flittering bubbles. All of this is accompanied by a confusion of sound rushing past your ears, followed by the strange sensation of buoyancy trying to reverse the process. You are soon right side up and floating on the surface. As you make the mandatory hand signal to indicate all is well, you embrace the fact that you’ve actually replaced the safety of the boat with the unknown. After all, this is what makes scuba diving so adventurous.

After a quick equipment check, it’s time for you and your dive buddy to begin the descent by deflating your respective BCDs. As you sink, the horizon disappears and you transition into an alternative, distinctively personal world. Unlike on the surface, you become acutely aware of the sound of your own breathing. Its steady rhythm seems to amplify and echo through the surrounding water. Meanwhile, a slight pressure builds in your ears, a discomfort that can be easily remedied with a pinch of your nose and a gentle exhale through closed mouth. You see your buddy equalise the same way while you both continue the descent. As the brightness above slowly fades away, it’s replaced by ever-darkening hues of blue, and you realise that you’re well on your way to the mysterious depths below.

The temperature drops notably as you pass through the thermocline. It is invigorating, adding to an already heightened sense of awareness. Far too deep to make it to the surface unassisted, your very life now entirely depends on your scuba gear and wits.

Your attention is soon drawn to a dark shape looming below in the blue gloom. As you get closer, the shape resolves itself into the unmistakable outline of a WWII aircraft. This is exactly what you’ve come to see and the excitement is tangible.

It’s a Bristol Beaufighter TF Mk X. Despite the rigours of current, corrosion, and trawling nets, its proud structure remains remarkably intact. This is not some restored museum piece, but the real deal. Once a symbol of the might and power of the Royal Air Force, it now lies silent and still on the seafloor at a depth of 105 ft (32 m), just as it has done for the last 80 years.

Dominating the expanse of the mid-mounted wings are a pair of mighty Hercules XVI 14-cylinder sleeve valve radial engines. Notably, the fairings have partially disintegrated and the engine mount struts are exposed. Each engine could deliver 1,770 hp (1,300 kW) at 2,900 rpm (500 ft or 150 m altitude). This meant a cruise speed of 300 mph (480 kph), max speed of 323 mph (520 kph), a service ceiling of 26,500 ft (8,000 m), and a range of 1,540 mi (2,478 km). It was these capabilities which made the Beaufighter Mk X such a capable ordinance delivery platform back in the day.

Source: Vasilis Mentogiannis ©

Most of the Beaufighter’s wings remain panelled, hiding ribs, spars and other features such as aileron cables and fuel tanks. The retracted undercarriage is also hidden, tucked away behind the engines since take off on the aircraft’s final flight all those years ago. Outbound, but still inside the propeller radius, there are a pair of oil cooler intakes protruding from the leading edge. These are a distinctive feature you’ll notice in any picture of a Beaufighter. As the wing tapers towards the wingtips, the outer sections are denuded, revealing that the six .303 in (7.7 mm) Browning machine guns (four starboard, two port – the asymmetry allowing landing lights in the port wing) have been removed.

Source: Vasilis Mentogiannis ©

Embedded in the sand, it is impossible to inspect underneath the aircraft. But a close look under the pilot’s position on the starboard side reveals one of its cannon blast tubes. This is where 0.787 in (20 mm) rounds shot out from one of four dorsally mounted Hispano cannons. In addition to the six fixed Browning machine guns and one flexibly mounted 0.303 in (7.7 mm) Vickers ‘K’ gun for the navigator/rear gunner (also missing on the wreck), there were hard points underneath the wings for four 500 lb (227 kg) bombs or, beginning late 1943 and early 1944, eight 60 lb (27 kg) solid rocket projectiles. This made the Beaufighter one of the most heavily armed long-range fighters of its time. When not carrying bombs (or rockets), the TF version, which this is, could carry one 1,760 lb (798 kg) 18 in torpedo.

The nose cone is missing on the wreck, but this reveals the otherwise unseen armoured plating forward of the cockpit. Beaufighters were famed for being able to handle a great deal of punishment, including fire from the ground. Set in the middle of the plate is the mounting point for the strike camera. This was automatically triggered when the weapons were fired, making for some spectacular combat photographs – a fact most especially true when they started fitting Beaufighters with solid rocket projectiles in lieu of torpedoes.

Source: Ken LaRock, National Museum of the U.S. Air Force ©

Source: Dr Scott Robertson ©

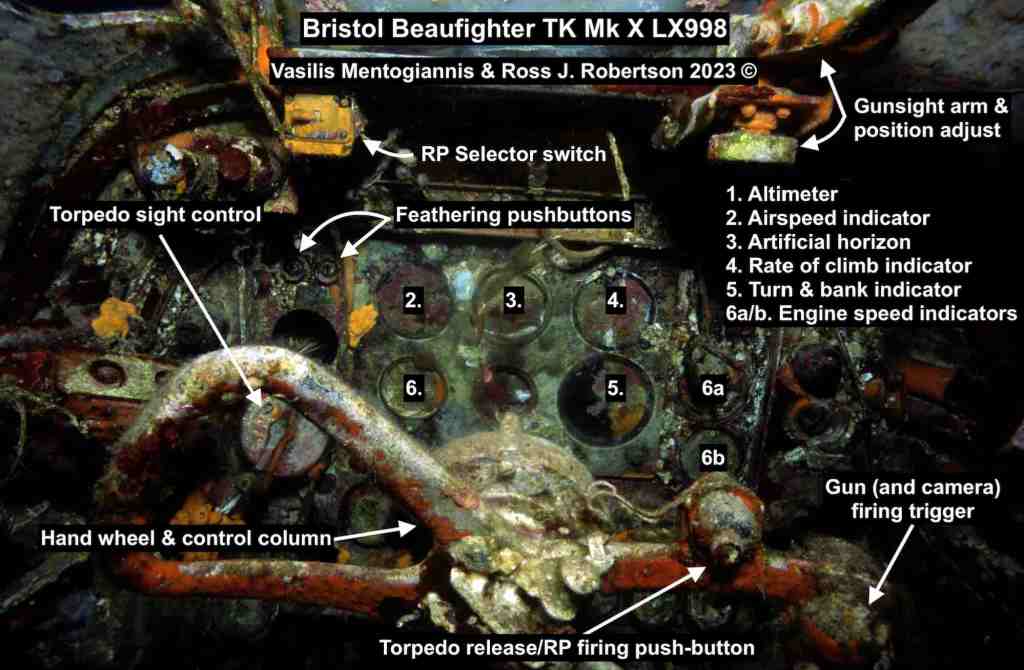

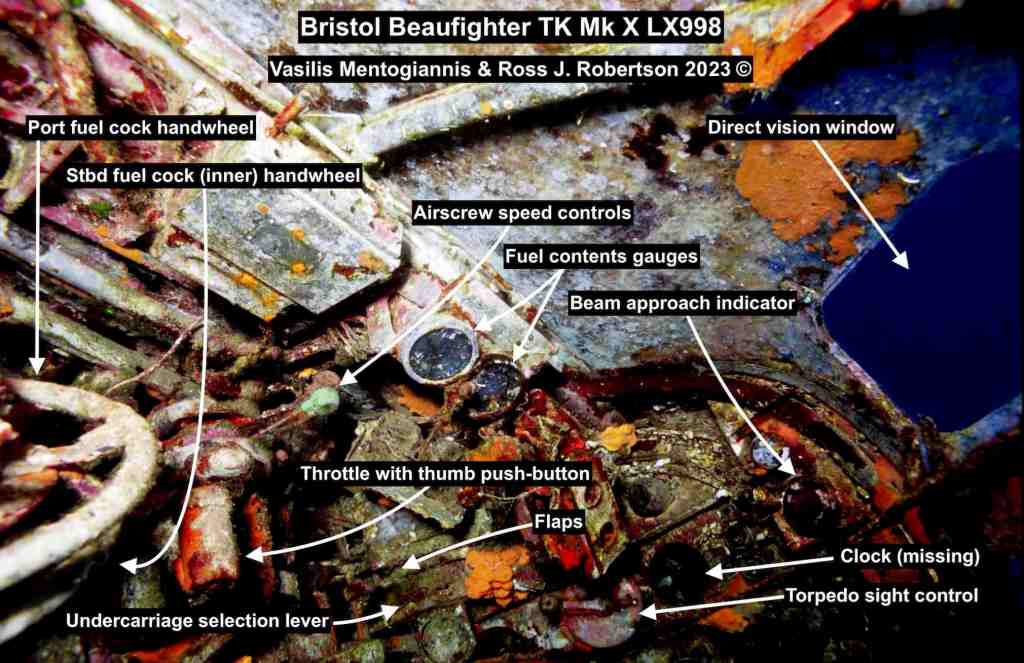

Excitement peaks as you ready yourself to inspect the cockpit. Poking one’s head through the open canopy with a flashlight reveals a riot of colour. Salt, rust and marine organisms have taken hold, making the perspex opaque and giving all surfaces in this confined space an orange and red hue. Before and on either side of the pilot’s collapsible seat are an assortment of identifiable instruments and controls. The wheel handle on the control column remains in place, and even the trigger mechanism is plainly seen on the right hand side. Looking aft, the triangular shape of the fuselage is immediately apparent. On the floor is the pilot’s closed escape hatch and on either side run wires and conduits. There is an armoured bulkhead between pilot and the rear of the aircraft, its connecting door is open to reveal the navigator/rear gunner’s position.

Source: Vasilis Mentogiannis ©

Source: Vasilis Mentogiannis ©

Source: Vasilis Mentogiannis & Author ©

Source: Military Wireless Museum Kidderminster, UK ©

Although temping, it’s too cramped to swim along the fuselage on the inside, but easy enough on the outside. Home to all manner of marine life, the open navigator/rear gunner’s observation canopy reveals the armoured swivel seat which remains facing aft. Immediately noticeable is a radio receiver on the port side, its central tuning knob and dial making it easily identifiable as a R1155 type, although it’s a little weird to see a fish meandering nearby. The T1154 transmitter was also standard kit on the Beaufighter Mk X, and this is located on the starboard wall of the fuselage towards the tail. This area is also where such things as oxygen bottles, drinking water and a sanitary bottle were stowed. Inspection of this confined space is possible from both ends as the tail section of the aircraft has partially broken away. This has also left the dihedral tail planes, fin and rudder at an odd angle.

The experience has been so absorbing that your allotted bottom time is close to maxing out, as a quick look at the dive computer and pressure gauge confirms. You signal your buddy that it’s time to go. As you swim slowly around the periphery of the wreck for one last time, taking in the full scope of its quiet majesty, you are left with a sense of wonder. How did this amazing machine end up in a watery grave in the Aegean?

You’ve actually seen all the pertinent clues. The aircraft is in one piece. It was clearly forced down for a reason, but equally obviously, it didn’t break up in flight or on impact with the water and create a debris field. It is found in relatively shallow waters just off the south-western coast of the Greek island of Naxos, suggesting that the pilot was more-or-less in control of the doomed aircraft and was trying to maximise the chances of survival. All three port De Havilland hydromatic propeller blades are bent and twisted backwards (the starboard blades are missing entirely). This only happens if they hit ground or water while the engine is still turning, which is another hint that the pilot was trying to ditch. The aircraft settled on the bottom the right way up. This indicates that the aircraft was inundated after being successfully ‘landed’ (and horizontal) on the surface. The pilot’s and navigator/rear gunner’s canopies are open, suggesting egress by both from the top of the aircraft, not via the escape hatches underneath (which would be used to bail out during flight). Rather than be slowly corroded away in situ, the rear panel on the port upper wing near the fuselage is completely missing. This is where the inflatable dinghy had once been – its immersion switch would have automatically triggered on contact with water to offer a chance of survival after egress. All these factors combined imply that both airmen were probably alive at the time of ditching. The question is, did they actually survive?

The short answer is ‘Yes’ – but probably not in the way you might expect.

Identifying the wreck

The wreck was discovered in 2007 by local professional diver Manolis Bardanis. For many years it was thought to be JM317 ‘S’ – the 47 Squadron RAF Beaufighter Mk X which pilot Flying Officer (F/O) William ‘Bill’ Hayter and navigator/rear gunner Warrant Officer (W/O) Thomas Harper (who was ‘borrowed’ from 603 Squadron for that single mission) were forced to ditch on 30 October 1943 after a strike on Kriegsmarine shipping in Naxos harbour. It was an automatic assumption as their rescue, facilitated by locals George Sideris and Dr Emmanual Bardanis at great personal risk, was well remembered on the island. However, it turns out to be another aircraft entirely.

“The wreck is actually LX998 ‘Y’ from 603 Squadron RAF,” explained Dr Kimon Papadimitriou of the University of Thessaloniki, Greece. He is head of the Underwater Survey Team (UST), a group of local professionals who are volunteer historical research and wreck hunting enthusiasts.

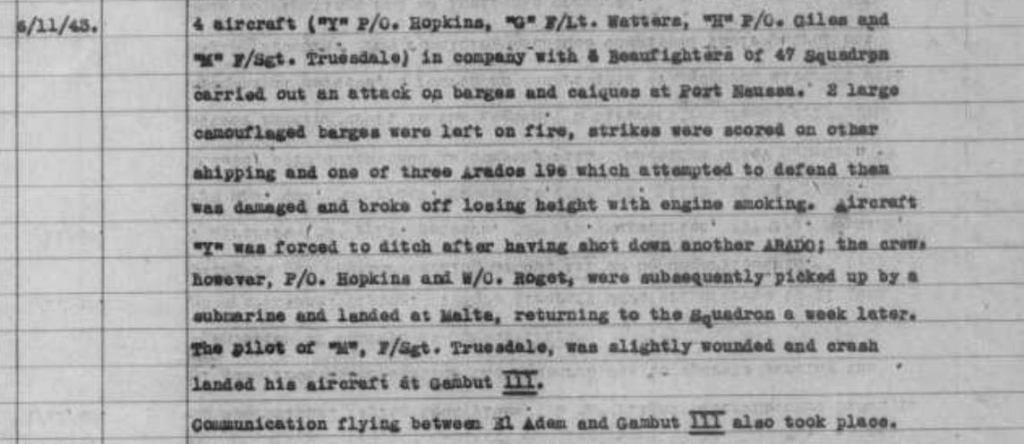

According to the archives, LX998 was among a group of eight 603 and 47 Squadron Beaufighters which launched an attack on the Naousa port and Yanni bay located on the northern coast of Paros island. The strike force encountered significant challenges during their attack, including heavy anti-aircraft fire and attacks by Luftwaffe Messerschmitt Bf-109s and Arado 196s, resulting in considerable losses.

“The aircraft was flown by Pilot Officer (P/O) Keith E.E. Hopkins, with W/O Keith V. Roget serving as navigator and rear gunner. Together with one of the other Beaufighters, Hopkins and Roget successfully carried out a cannon attack on two camouflaged barges and four caïques. Additionally, they reportedly shot down an Arado 196 that was defending the area, but were eventually forced to ditch near Naxos on 6 November 1943,” Dr Papadimitriou said.

Both airmen survived the ordeal and made it out of LX998 as it flooded and sank. They managed to get to the dinghy, but not to shore. Whether they were too exhausted, injured or the current was simply too strong to paddle to Naxos is unclear. What is known, however, is that they were carried by strong winds in a south-easterly direction for nearly 30 nautical miles. This took them tormentingly past the islets of Iraklia and Schinousa and many miles out to sea. All must have seemed lost when they were miraculously spotted by a Royal Navy submarine, as recorded in its commanding officer’s (Lieutenant H.B. Turner, DSC, RN) logbook:

“6 Nov 1943: At 18:03 hrs (time zone -2), HMS Unrivalled, picked up two RAF pilots of a Beaufighter of 603 Squadron and their rubber dinghy near position 36°40’N, 25°47’E.”

The official RAF archives also concur with this happy ending:

“Aircraft ‘Y’ was forced to ditch after having shot down another ARADO; the crew, however, P/O Hopkins and W/O Roget, were subsequently picked up by a submarine and landed at Malta, returning to the squadron a week later.”

Whether you’re a beginner or an experienced diver, this 105 ft (32 m) dive is well within non-decompression limits. As anyone who has had the privilege will confirm, visiting the underwater wreck of a WWII aircraft is a unique and unforgettable experience. Not only does it provide a rare opportunity to connect with the past in a uniquely tangible way, but it also allows a deeper appreciation for the heroic efforts and sacrifices that were made during the war. It is a powerful and humbling experience that reminds us of the importance of remembering and honouring our shared history. As such, it is truly immersive in both senses of the word.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Vasilis Mentogiannis for his underwater photography of the LX998 wreck. Many thanks also to Panagiotis Niflis of Bluefindivers Dive Centre, Naxos (bluefindivers.gr) for his invaluable assistance. Both the Moorabbin Air Museum, Melbourne Australia and the Military Wireless Museum, Kidderminster, UK are recognised for their kind assistance. Finally, gratitude is also extended to Dr Kimon Papadimitriou and fellow members of the Underwater Survey Team (wreckhistory.com) who were involved in this project.

References

HMS Unrivalled: ADM 199/1821

No. 603 Sqdn RAF ORBs: AIR-27-2079-60, AIR-27-2079-61

Featured (cover) image: ‘Bristol Beaufighter Mk X LX998 rests on the seabed off the coast of Naxos in the Aegean. Source: Vasilis Mentogiannis ©

Footnotes

- “6/11/43. 4 aircraft (“Y” P/O. Hopkins, “G” F/Lt. Watters, “H” P/O. Giles and “M” F/Sgt. Truesdale) in company with 4 Beaufighters of 47 Squadron carried out an attack on barges and caiques at Port Naousa. 2 large camouflaged barges were left on fire, strikes were scored on other shipping and one of three Arados 196 which attempted to defend then was damaged and broke off losing height with engine smoking. Aircraft “Y” was forced to ditch after having shot down another ARADO; the crew, however, F/O. Hopkins and W/O. Roget, were subsequently picked up by a submarine and landed at Malta, returning to the Squadron a week later. The pilot of “M”, F/Sgt. Truesdale, was slightly wounded and crash landed his aircraft at Gambut III.

Communication flying between El Aden and Gambut III also took place. “

AIR-27-2079-60 ↩︎

We value your opinion!

Your feedback is important to us. If you enjoyed this article and would like to see similar content, show your appreciation by clicking the ‘Claps’ icon below. Also, ensure you stay up-to-date with our latest articles by subscribing to our Newsletter. You’ll receive new posts directly to your email inbox. Thank you for your support!

‘History has to be shared to be appreciated’

Subscribe to our Mailing List. We’ll keep you in the loop.