by Vasilis Mentogiannis and Ross J. Robertson

A truncated version of this article entitled ‘Junkers JU-88 is Aegean plane wreck star’ was first published in January 2024 on Divernet.com UK.

Explore the depths of history with ww2stories.org as you embark on a fascinating account of how professional divers Vasilis Mentogiannis and Yannis Goulelis found a rare Luftwaffe Junkers 88 bomber in the Aegean.

“I found myself alone in a very remote place on a fine autumn day back in 2005,” recalls Vasilis Mentogiannis. “Our inflatable boat, laden with diving paraphernalia and underwater camera gear, gently bobbed on the calm surface. Never one to give up easily, my companion Yannis Goulelis, had just splashed into the water, leaving me entirely alone for the first time during our search. I was left to gaze at the old, abandoned lighthouse, my mind a swirling turmoil of doubt.”

Known as the ‘Eye in the North’, they were anchored just off the small island of Psathoura, which lies at the northernmost tip of the Sporades archipelago in the Aegean. Being so exposed, the area is normally quite dangerous – a fact defining the island’s solitary feature, a lighthouse accompanied by long-deserted living quarters at its foot. Standing at almost 30 metres, the proud stone structure, now solar-powered and automated, continues to safeguard maritime traffic, a duty it has fulfilled since 1895.

Source: Vasilis Mentogiannis ©

This was the end of the second day and the eighth dive of their search. From their temporary base at the small harbour of Steni Vala on the island of Alonissos, the boat trip out to Psathoura took about an hour and a quarter at a speed of 17-18 knots. Nobody lives this far out anymore. There is ubiquitous GPS to determine position, but there is no mobile phone signal coverage, only the boat’s VHF radio should something go wrong.

A local fisherman, Georgios Drosaki, had given them the coordinates two years previously over a taverna meal at Steni Vala in the cool summer evening. The food had been accompanied by good wine and further embellished with maritime stories of a local wreck. They were determined to go there and then, but the weather closed in and the opportunity was missed.

Preparations

However, the story was far from forgotten and Vasilis – a professional diver with experience of searching out wrecks – delved into the archives when he got back to Athens. He also sought out people who might know and remember what had happened in such a remote place during the 1941-1944 Axis occupation of Greece, so many years ago.

Financial support was required for the undertaking, so Vasilis soon found himself in the offices of Thalassa magazine (a Greek magazine for Boat-Fish-Dive).

“What exactly do we know about this?” the editor, Manolis Evgenitakis asked.

“Not much,” Vasilis admitted. “Only the fisherman’s description, that it’s supposedly in very good condition, and that he’ll help us find it.”

“I see… Do you think it’s worth it?” Manolis inquired, an obvious look of doubt etched on his face.

“I think so,” Vasilis answered sincerely. “We also have testimony from the lighthouse keeper’s son. We know that the crew was saved and we know the type of aircraft. It’s a WWII German bomber – a Junkers 88,” he added, hoping that it might elicit a reaction, given the historical significance.

The Manolis just stared back.

Vasilis’ last wreck-hunting escapade, off the island of Ithaca on the western seaboard of Greece, had ended in disappointment. Despite an exhaustive search, the rigours of time had demolished and scattered the wreck. They only found the partial remains of two engines and a small piece of tail section. The rest of the Junkers-88, which they were after, had gone forever. There was the promise of a couple of other WWII aircraft wrecks near Piraeus, otherwise the wreck in Psathoura was their best chance of turning up something new.

“We’ve never found an entire aircraft,” Vasilis continued, “So, yes. In my opinion, it’s definitely worth a shot,” he confirmed, hopefully.

The editor offered a nod of resignation, and the hunt was suddenly on.

Day one

That was several months ago. Now that they were actually on site, things had proven more difficult than Vasilis had so optimistically believed when he was preparing for the expedition.

Even armed with GPS coordinates and a target depth of 32 metres, both given by the fisherman, the first day had not gone as well as originally hoped. While they approached, Vasilis read off the co-ordinates from a hand-held GPB device as Yannis skippered the boat.

“Right here… Hold!” Vasilis shouted from the prow, his voice cutting through the racket of the outboard engine directly behind Yannis. The boat slowed down and glided to a suspenseful stillness on the calm water.

“Depth?” Vasilis questioned.

“It’s 44 metres (144 feet),” came Yannis’s response as he read the boat’s depth gauge on the instrument console.

Vasilis’ brow furrowed; the depth should be a precise 32 metres (105 ft) at this very spot. “Let’s keep going until the depth gauge reads 32,” he suggested. In terms of underwater navigation, the only absolute in the diving world is depth.

The boat inched forward until, finally, Yannis exclaimed, “Here! 32! We are here!”

The anchor was dropped, the engine shut off, and preparations for their first dive into the mysterious depths below made. However, as they donned their gear, an unsettling feeling persisted. The depth was correct, but outlines of the seafloor were just visible through the pristine water. At 32 metres, that should not have been possible.

With hands secured on masks and second-stage regulators, they plunged backward over the side. A cascade of bubbles enveloped them momentarily, and the gentle embrace of positive buoyancy swiftly brought them upright, bobbing on the rippling surface. Following a final gear check, a synchronised release of air from their BCDs took them under.

Their descent was swift and they found themselves hovering just above the seabed before expected. In contradiction to the anticipated depth, their instruments registered a perplexing 19 metres (62 ft). A shared moment of confusion passed between them, mirrored glances conveying the unspoken question – was the anchor dragging? Had they inadvertently drifted into shallower waters during the descent? It just didn’t seem possible.

Some 40 minutes of suspenseful exploration yielded no noteworthy discoveries. However, air consumption did compel both to ascend with a measure of disappointment. After breaching the surface, a strong current fought against their return to the boat. Exhausted, they eventually clamoured aboard. Vasillis anxiously checked the boat’s depth gauge, soon finding that it was still reading 32 metres.

The anchor had not dragged and the boat hadn’t moved: they were in the wrong place.

A quick underwater inspection revealed some damage to the underside of their rented boat, including around the sensor. Was this the cause of the unreliable depth readings? The obvious thing was to go back to the original GPS coordinates. So, they weighed anchor and went back, in spite of the lingering doubt cast by the unreliable depth gauge.

Yannis questioned, “What’s the plan?” to which Vasilis responded, “We’ll tether my dive computer to a weighted line, drop it overboard, and record its maximum depth. It’s our best chance at obtaining accurate measurements.”

In a tense interlude, they successfully captured a depth of 34 metres (111 ft) while within acceptable parameters of the GPS coordinates. That seemed close enough. So, with the anchor dropped once again, they prepared themselves for another dive, still more than eager to unveil the secrets hidden beneath them.

Following their descent, the depth on their dive computers read a consistent 34 metres. However, as they ventured a bit further, the seafloor unexpectedly plummeted to 40 metres (131 ft), contradicting what the fisherman had told them. Undeterred, they pressed on with their explorations.

By half-past three in the afternoon, concluding their fourth and final dive of the day, any remaining hopes of a breakthrough had shattered. However, at this critical juncture, Yannis made a pivotal discovery at the very end of the last dive. Aware of his limited bottom time, he swiftly secured a decompression marker buoy to the find, inflated it and watched it shoot up to the surface before joining Vasilis on their much slower ascent back to the boat.

On the surface, they were embraced by a renewed sense of hope.

“What happened? What did you see? Tell me!” Vasilis implored with excitement.

“I found a piece of cockpit canopy, and not far from it, what I believe to be a section of tail fin,” Yannis replied.

“That’s it? Anything else?” Vasilis probed further, anticipation clear in his voice.

“No, nothing else,” was the response. “It’s very odd,” he added slowly, leaving both puzzled.

The sun was getting low and an autumn chill began settling in. Yanniss’ small inflatable marker buoy bobbed in the sea not too far away, as if teasing them. Thoughtful and cautiously optimistic, there was nothing they could really do but to embark on their lengthy return journey to Alonnisos.

Over an evening meal, they recounted the day’s events to Drosos Drosakisi, a local and old friend who had helped them stage the exploration.

“It just can’t be!” he exclaimed, refusing to accept the possibility that the wreck might slip through their fingers, despite all the effort.

Both Vasilis and Yanniss knew well that aircraft wrecks are relatively small and are easily missed in the water. Even if intact, they still have the potential to elude the keenest eyes. However, if scattered – as the discovery of the canopy seemed to indicate – the problem is exacerbated by several orders of magnitude. Experience told them that limited visibility, reduced light, and a finite bottom time also work against discovery, so they had to come up with a plan.

Day two

The following morning, they set out under a brilliant autumn sky and raced across a smooth surface to the Psathoura lighthouse with restored optimism. They soon found the marker buoy Yannis had left yesterday. Using this as a reference point, they created four distinct search areas, one for each of the day’s allotted dives. These were designated by dropping additional buoys over the side, the trick being that each had to be equidistant to provide a methodical means to cover the underwater terrain. This, in turn, would ensure that every corner of the specified region could be meticulously examined, leaving nothing missed.

The initial dives yielded no results, yet their optimism persisted. However, as the fourth and final dive concluded without any discoveries, disappointment and a sense of despair began to take hold. Fatigue had also settled in. With the clock ticking toward three o’clock, they sat in the boat during a moment of quiet reflection, the only sound being the sea gently lapping against the hull. They were surrounded by serene wilderness, with the distant lighthouse standing as a steadfast challenge to their resolve.

Yannis suddenly spoke, his sense of urgency and determination cutting through the melancholic air like a knife. “Why not search from where I found the canopy to the shallowest point we reached yesterday? That would take us right across the 32 metre contour line.”

“But we covered that area yesterday,” Vasilis replied wearily. “We’d have seen something, if it were there.”

“I’ll go,” Yannis insisted.

Vasilis knew his friend well. There was no point trying to persuade him to delay until tomorrow. “If you have the strength and will, okay do it. We still have two full tanks of air – take one of them.”

Yannis didn’t bother to change over the tanks and almost immediately splashed over the side, the speed an embodiment of his determination.

It was now that Vasilis was left entirely alone, gazing at the old, abandoned lighthouse with his mind in a swirling turmoil of doubt.

He contemplated the very real possibility of never finding the wreck. How would he explain the failure to those who had placed so much faith in him – his friends, family, not to mention the magazine editor? Even if an intact wreck was found soon, there would be barely enough time to examine it in detail before they had to return to Athens.

Eureka!

His thoughts were suddenly distracted by a familiar sound. Another of Yannis’s decompression buoys had suddenly shot up to the surface, not far from the boat. The implications were twofold: either the aircraft had been found, or his friend was in some kind of trouble.

With urgency, Vasilis hastily grabbed his mask and fins. However, before he could prepare to dive, Yannis broke the surface, removing his respirator to unveil a broad smile. “I found it! It’s here!” he exclaimed while pointing below.

It was a shared moment of pure elation!

Enthusiastically, Vasilis continued with his preparations, recognising that this time, the underwater camera and additional lights would be indispensable. He paused for a moment, mentally preparing to witness something that had only existed in his imagination until that day, and then he splashed over the side to join his friend in the discovery.

“No matter how many years elapse, the very first moment when you encounter a wreck – that initial image – remains indelibly engraved in your mind forever,” Vasilis says as he recounts the events of 2005. “We were approaching a depth of 32 metres when, right before us, the eerie sight of a silent aircraft resting on the dark rocky bottom unfolded. It was genuinely awe-inspiring,” he reflects.

They soon realised why they hadn’t spotted it earlier, even though they had passed near its location at least three times. Surrounded by rocky outcrops that created a trough, the aircraft was effectively concealed from most angles. From the cockpit, which, of course, was missing its canopy, they conducted a quick precursory investigation, confirming that the Ju-88 was fundamentally intact and lying at 32 metres. However, as this was Yannis’s second dive on the same tank, air was running perilously short.

“Securing a rope to the wreck for the next day’s descent, we surfaced with a strange mix of excitement and relief engulfing us,” recounts Vasilis many years later. “Quite a moment,” he adds, smiling.

Day three

Despite lingering fatigue caused by a combination of previous excursions and an almost total lack of sleep the previous night due to raw excitement, fervour propelled Vasilis and Yannis back to the discovery site first thing next morning.

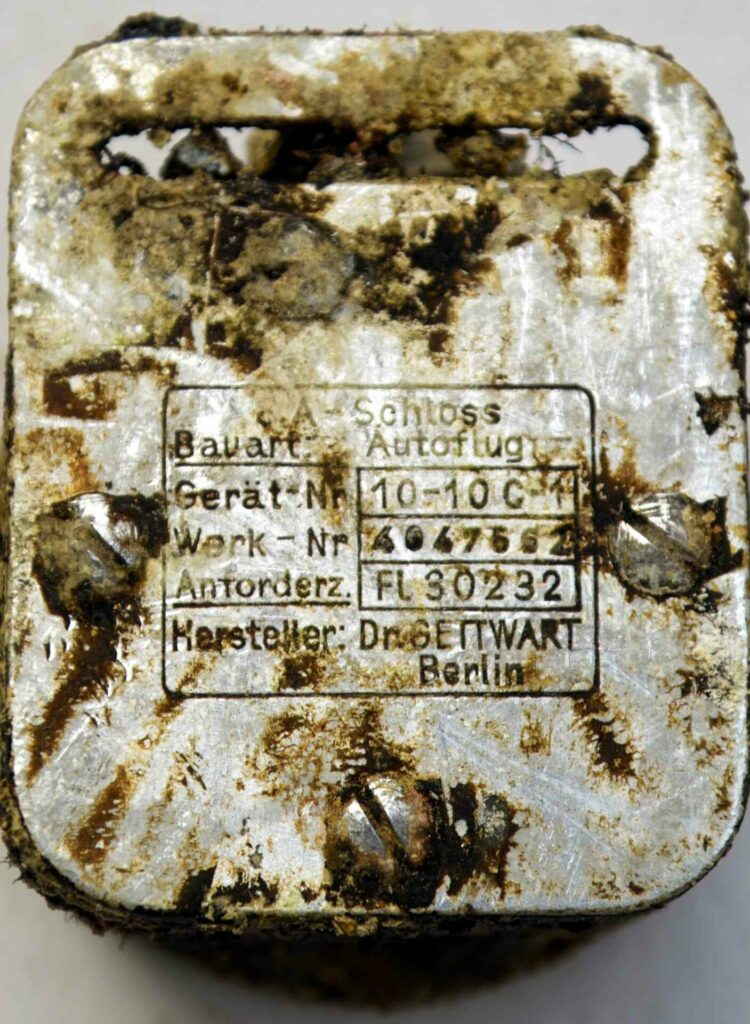

Following the drop-line they had secured the previous day, they swiftly reached the site. Their new plan, discussed excitedly the previous evening, was clear – to explore the surroundings and, crucially, locate the small metal ID plate engraved with the aircraft’s serial number. This held the key to identifying both the aircraft and its crew. Guided by instructions from German historians, they knew the ID plate should be on the starboard (right) side, just below the pilot’s window, or alternatively, roughly in the middle of the instrument panel inside the cockpit. Despite good visibility in the clear water, the cloudy weather above diminished available light and cast a deep blue hue on the water at the depth where the virgin WWII wreck lay.

They descended, camera equipment in hand. As the silhouette of the aircraft materialised in the ethereal blue, anticipation intertwined with increasing trepidation as they began their investigations. The wreck was not in as good condition as they had initially thought, revealing the vulnerability of its submerged existence.

Navigating along the wreck’s dorsal line, the basic form of fuselage and wings was evident. Indeed, it hinted at the aircraft’s former glory. However, the tail section had crumbled into fragments and two heavily corroded engines lay detached in front of the wings. There were no propellers, their absence possibly suggesting a forced ditching. Otherwise, there was no direct evidence, such as damage sustained during combat, to explain why the plane had ended up so forlorn at the bottom of the Aegean.

Without the protection of the canopy, the cockpit, once the proud place of command and control, had yielded to the relentless embrace of the sea – its almost complete degradation presented a serious obstacle to their quest to find the metal ID plate. Was it concealed within the scant vestiges of the cockpit? Scattered instruments, assorted debris, and even a crew seat lay all around outside the fuselage. Could it be there? Irrespective of where it might be, had it corroded beyond recognition, or simply disintegrated entirely?

On the slim chance that the ID plate might still be affixed to a fragment of the dashboard or window frame, they examined any sizeable piece of metal within the cockpit area or scattered outside in the vicinity. However, their endeavours over several ensuing dives proved futile.

As they emerged from the depths after their final dive, the realisation dawned that their work had only just begun, if they were ever going to properly identify the time capsule they had just discovered.

An eyewitness account

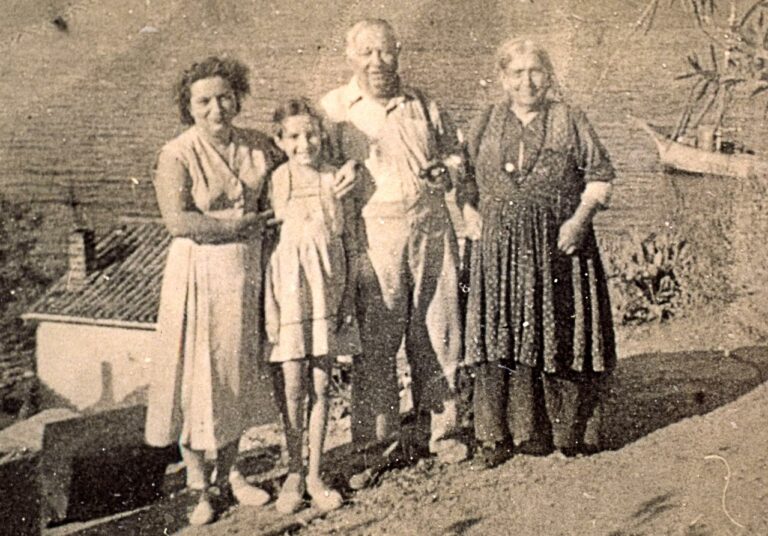

Giorgos Agalou was the son of the Psathoura lighthouse keeper. He was born in 1916 and was 26 years old during the height of the Axis occupation of Greece during WWII. In a fascinating interview found in a book entitled ‘Upper Magnesians Islands’ by Kostas Maurikis, conducted on 2 June 1996 at Steni Vala, Alonissos, a first hand account of the Ju-88’s fate is disclosed:

“During the Second World War, my parents and I were inhabitants of Psathoura. In that period, there were a few incidents which disrupted our tranquil and secluded existence.

The most memorable occurred on 27 May 1942, during a quiet night illuminated by a full moon. The distinct drone of an aeroplane engine resonated closely above us. The aircraft circled the lighthouse, which, due to wartime conditions, remained unlit unless officially requested by government order. Fearing potential bombardment, as the source of the noise was uncertain at that time, we ventured outside and sought refuge in the surrounding bushes. It was 2 o’clock in the morning, and the weather was clear. We could clearly discern a large plane circling above.

Suddenly, the engines stopped and there was no noise. The pilot skillfully brought the aircraft in low and made a controlled ditching in the sea. It ploughed a considerable distance across the surface before coming to a stop and submerging.

Meanwhile, the crew hurriedly abandoned the aircraft using a life raft. My father and I shouted directions to them, signalling a specific spot where they should paddle to shore. He was a smoker and lit several matches to help guide them.

When they reached safety, they lifted the life raft out of the water and deposited it on the shore. After expressing their gratitude, we all headed toward the lighthouse. There, my mother offered them food. It was declined. Instead, they opted for fresh onions from our garden as they were apprehensive about potential poisoning. Afterward, they improvised a wash by pouring water from the cistern on each other using an old petrol can. Subsequently, they dozed off, assigning one of their four members to stand guard in shifts.

On the following morning, the crew inquired about their location, the possible presence of partisans, and the possibility of joining their fellow Germans. Among the crew members was an Austrian who spoke Italian, a language my father was familiar with, having served in the Royal Hellenic Navy. This enabled us to learn their story – a Junkers 88 bomber en route from Tobruk to Sicily was pursued by Allied planes, prompting them to alter course for the Aegean. Exhausting their fuel above Psathoura, they had been forced to ditch.

The inflatable dinghy they used to save themselves turned out to be a heaven-sent boon for us. We crafted numerous pairs of makeshift shoes from the robust rubber, both for ourselves and our relatives.

I took them on my small boat, the sole means of departing our remote island. Aided by the spring winds, we sailed to the Kyra Panagia monastery. Monks Benjamin and Athanasios hosted us, though they were apprehensive due to their previous involvement in the theft and sinking of a boat.

The following day, we reached Alonissos. Dr Tsoukanas took them in. We rowed to Skiathos the next day, where the crew were united with the local German garrison.

Grateful for the assistance my family and I had offered them, one of the crew members gave me a photograph of himself, with a message inscribed on the back. When I was later apprehended by the Germans during a rounding-up operation in the Northern Sporades, I presented this photograph to my captor. He snapped to attention upon recognising the image and I was spared.”

A book by Kostas Mavrikis entitled ‘Upper Magnesia Islands’ 1 also makes mention of the Ju-88 in the area:

“My friends, sponge divers Giorgos Drosakis from Alonnisos and Lefteris Glynatsis from Kalymnos, discovered the aircraft at a depth of 30 metres. The aircraft had sunk quite far from its ditching point. Its overall condition is good, except for certain sections that have detached and are scattered in the area…”

Why so much damage?

An enigma lay in the contrast between both narratives and the condition of the wreck rediscovered by Vasilis and Yannis. Clearly untouched by combat damage, the aircraft was airworthy when, having depleted its fuel, it came down. The crew’s successful launch of the inflatable dinghy and self-rescue meant that the aircraft, especially the cockpit, which was the point of egress, had survived the ditching largely intact, as opposed to breaking up and scattering across the seafloor.

In more recent times, a significant portion of the area around Alonissos, including the Eye of the North, has been designated as a marine park, offering substantial protection for the monk seal and against fishing activities. This also bodes well for the preservation of the wreck. Even prior to this designation, any assumption that the aircraft had been dragged and partially destroyed by trawling nets, a fate befalling many aircraft wrecks, did not hold true. The local seabed topography prevented fishermen from trawling in the area. The long-outlawed practice of dynamite fishing was a remote possibility, given the 32 metre depth. Explosive damage, if any, might have resulted from depth charging or a wandering shipping mine, but this explanation failed to clarify why the tail section appeared shattered by physical impact rather than a pressure wave. Another, perhaps more plausible hypothesis, simply considered the influence of intense seas and underwater currents, consistent with the region’s known conditions.

However, the exact cause – or combination of causes – will probably never be known.

Follow up

Two subsequent trips to the site within their remaining allotted time proved unsuccessful in locating the ID plate. Nonetheless, Vasilis and Yannis managed to salvage intriguing artefacts for preservation. Among these were a distress flare gun, a lamp, a safety belt buckle from one of the crew seats, and several bullets. The most notable discovery was a MP-40 ‘Schmeisser’ submachine gun accompanied by six magazine clips.

Source: Vasilis Mentogiannis ©

As the time neared its end, they had to bid farewell. Returning the boat and expressing gratitude to Drosos, they also pledged to come back for a simple vacation. Both divers then packed their gear and boarded a commercial ferry bound for Volos on the mainland.

Upon their return, they promptly delivered the findings to the Hellenic Air Force for preservation and cataloguing. Time was of the essence, as drying and exposure to the air would be detrimental to the artefacts. Squadron Leader Yanniss Karantanis, the director of support and maintenance at the Hellenic Air Force Museum at that time, warmly welcomed them and assisted in completing the necessary paperwork.

“I will transfer them to the maintenance and restoration workshop without delay,” he said. “And don’t worry, I will keep you informed as soon as I receive updates,” he assured them.

Source: Vasilis Mentogiannis ©

The question of the wreck’s identity lingered. Knowing the aircraft type and exact date of ditching did offer some chance of finding out through the surviving Luftwaffe records in Germany. So, they sent emails detailing all the information they had gathered and did their best to wait patiently for any response.

In the interim, they paid a visit to the Hellenic Navy’s Lighthouse Service, seeking data on the lighthouse and its keeper from that period. Although they eventually located the Lighthouse Keeper’s Register, the log and reports were conspicuously absent. Lieutenant Dimitris Patsopoulos informed them that the records from that time had either been lost or were never documented due to the war.

Undeterred, they persisted, making a series of phone calls that led to Mrs Melos Foula in Ermioni, a small coastal town in the Peloponnese. She was the granddaughter of Agalos Agalou, the lighthouse keeper, and George Agalou’s niece. Mrs Foula graciously shared old photographs and even presented them with a fork that belonged to the German crew.

Source: Vasilis Mentogiannis ©

“I was holding a fork in my hands,” recounts Vasilis. “The tainted metal was testimony to its age. I inverted it to inspect the underside of the handle, just where it widens at the end. I saw what I was expecting; an engraved Nazi eagle with the German swastika firmly caught in its claws.”

“It was truly astounding – a German warplane forced to ditch in the Aegean, the lighthouse keeper’s family on Psathoura, and now a fork in Ermioni. The fork in particular transformed the existence of the crew from a historical fact into a tangible reality,” he explains.

Identification

Desperate for news regarding the identification of the aircraft and crew, Vasilis eagerly checked his messages each day, yet there was nothing. Despite the silence, he maintained confidence that a response would come. He understood that the frustrating delay was likely the result of ongoing efforts. When there’s hope for a new piece of the historical puzzle to emerge, researchers tend to be both tenacious and especially meticulous. Having done all he personally could, he found himself in a waiting game, as exasperating as it was.

Then, the first message arrived from Dave McDonald in New Zealand, an expert in aviation history. In a concise sentence, he informed Vasilis that their plane appeared to be a Ju-88 A4 variant, with a war production number of 140225 and the callsign B3+MH. It belonged to 1./KG 54 (1. Staffel (1st Squadron), Kampfgeschwaders 54 (Bomber Wing 54)) and was piloted by Leutnant (Lieutenant) Haso Holst.

Vasilis quickly responded, asking for more details and inquiring about the possibility of locating the crew so many years later. At the same time, a second message arrived from Germany. Their contact, renowned historian Peter Schenk, confirmed the identification.

After consulting Siegfried Radke’s book on Kampfgeschwader 54 (Combat Wing 54), 2 Peter contacted them two days later, providing comprehensive information about the Luftwaffe squadron in question. The following details are extracted and translated from authentic Luftwaffe Diaries:

“26th May 1942: Nine Junkers-88 aircraft took off from Elefsina airport at 14:00 hrs on a mission to bomb the Gambut and Abiar Zaid airdromes. They also targeted a convoy of trucks carrying munitions. After refuelling at Tympaki in Crete, five of the aircraft took off again on another mission at about 19:50 hrs, aiming to bomb a convoy of trucks on the Bardia-Tobruk road. Failing to return, it was assumed that B3+MH with Lieutenant Holst and crew had ditched due to running out of fuel. Communication had abruptly ceased, and no further information was available.”

“28th May 1942: A report from the missing crew arrived, stating that they were well and making their way back to the Squadron.”

“30th May 1942: The crew arrived back at Elefsina airfield. They reported that, after damage to the aircraft’s compass was sustained while returning from their mission in N. Africa, they missed Elefsina airport. After many hours of flight, they ran out of fuel and ditched on 27th May at 01:02 hrs, near the island of Psathoura (Northern Sporades). The plane sank, but the crew reached the islet using an inflatable lifeboat and was saved.”

The research continued, with new evidence pouring in daily. Kampfgeschwader 54 was stationed in Italy in 1941, and a detachment was sent to Elefsina, with another detachment later dispatched to Crete. Holst returned to Italy on 21 July 1942. Unfortunately, no additional information was discovered about the rest of the crew – bombardier Joachim Elsasser, radio operator/gunner Gerhard Richter, and rear gunner Alfred John.

Their efforts were focused on the hope of finding any of them alive until a sobering message from Dave McDonald, a New Zealander and writer for the magazine Wings, reminded us of the brutality of war:

“On 14th of October 1942, during an operation to Hal Far on Malta, Holst’s plane was shot down and crashed into the sea. The entire crew was lost.”

Remarkably, it later turned out that there was actually one survivor – Lieutenant Holst. Despite attempts to locate him through the German archive service at Freiburg and Germany’s telephone directories, their efforts were in vain.

In a final communication with Junkers aircraft specialist, Philn Mertens in Belgium, they were cautioned that finding Holst would be exceedingly challenging. However, he connected them with three Luftwaffe veteran pilots. After sharing the story with them, they pledged to do everything possible to assist the quest. This included an intention to publish a notice asking for information about Lieutenant Haso Holst in the Jäger Blatt, 3 a specialist veteran magazine with a readership extending as far as Australia.

That was back in June 2005. In spite of concerted efforts to contact Holst and inform him of the discovery of his plane 63 years after the fateful night in 1942, no response was ever received.

Since 2022, the Greek government has officially sanctioned recreational scuba diving at 91 designated sites across Greece, including the Ju-88 wreck found by Vasilis and Yiannis in the Eye of the North. Regulations require divers to complete paperwork, and any disturbance or artefact collection is strictly prohibited to preserve these underwater treasures. This initiative is in accordance with the UNESCO conservation agreement on Underwater Cultural Heritage, emphasising in situ preservation, non-commercialisation, and the dissemination of educational information about culturally significant sites.

Despite the remote location off Psathoura, the wreck’s depth of 32 metres makes it easily accessible to divers of all expertise levels. It’s a dive enriched by both the event of its wartime fate and the more recent journey of its rediscovery.

Delve Deeper

The Restoration Process: Preserving Aviation Metals

by Lieutenant Dimitris Printezis, Hellenic Air Force

In adherence to the guidelines provided by the US Air Force and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), the restoration of aviation metals – such as aluminium, steel, and high-strength steels – involves the use of acid solutions. These solutions, comprising phosphoric and sulfuric acid, are tailored to the condition of the metals and the desired level of restoration.

Source: Vasilis Mentogiannis ©

Phosphoric acid, a key component, initiates a protective process called phosphating, forming a stabilising film on the metallic surface to safeguard it from future corrosion. Simultaneously, sulfuric acid serves to diminish oxidation and rust, exhibiting a chemical interaction with salt. Consequently, the sulfuric acid needs periodic replacement during the restoration process. In cases where a metal object has been submerged in the sea for an extended duration, resulting in heightened salt infusion, a solution of 20% phosphoric acid and 5% sulphate is utilised for its heightened reactivity against salt. However, to mitigate potential alterations to the metal surface, the object is immersed in the acid mixture for a maximum of seven minutes.

Source: Vasilis Mentogiannis ©

Source: Vasilis Mentogiannis ©

Following each immersion, the object undergoes thorough rinsing with pure water and meticulous inspection. This process is iterated until the desired restoration outcome is achieved. Complementary physical methods, such as using a soft or hard wire brush, a spatula for flat surfaces, and a water jet, are employed to delicately remove any marine encrustations.

With the metal now restored to a clean, bare state, the subsequent step involves the application of wax or anti-corrosion oil, ensuring preservation in a controlled environment with regulated temperature and humidity.

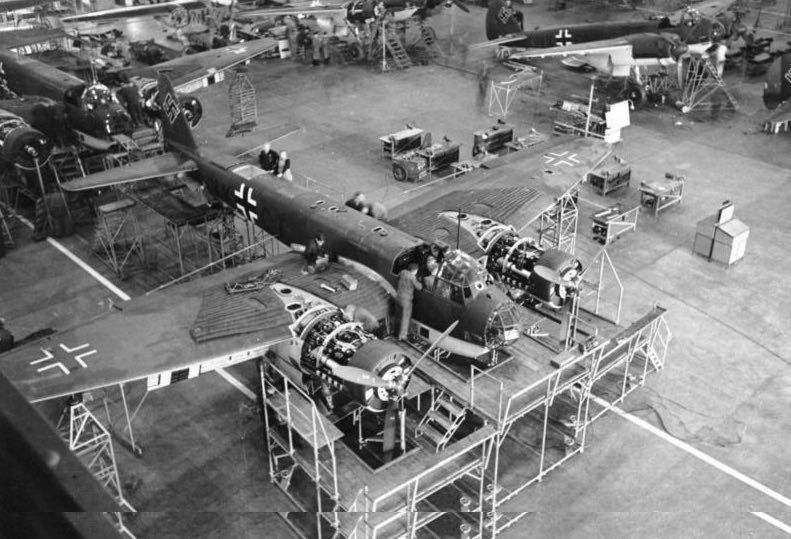

Luftwaffe’s Stellar Performer: The Ju-88

The Ju-88 (Junkers-88) emerged as one of the German Air Force’s premier aircraft during World War II. Initially designed as a bomber, it seamlessly adapted to diverse roles, showcasing its versatility in reconnaissance, night tracking, ground support, sea target attacks, and supply transport. In the war’s later stages, it even served as a flying bomb. 4 It excelled in challenging missions across all theatres, except in engagements involving close dogfights.

Ju-88s were manned by a four-member crew comprising a pilot, a bombardier, a radio operator/gunner, and a rear gunner. The A-4 variant, an enhanced version which first appeared in 1940, had a stronger airframe and was particularly useful for shipping attacks. It had an extended wingspan (20 m) as a result of redesigned wingtips and a standard fuselage length of 14.40 m. A sturdier undercarriage and capacity for four external bomb racks were also a feature. It was powered by twin Jumo 211 J-1 or J-2 engines generating 1,050 kW (1,410 hp), giving it a maximum ceiling of 8200 m, range of 2,730 km, and an impressive top speed of 470 km/h (at 5,300 m). The Ju-88 A4 was typically armed with either one 13 mm MG131 or two 7.92 mm MG81 in the nose, two MG81 in the rear of the cockpit, and two MG81 in a ventral gondola, and had a maximum bomb load of 2,000 kgs.

The Ju-88 played a significant role in the German invasion of Yugoslavia and Greece (Operations 25 and Marita, respectively) in April 1941. Notably, Staffelkapitän (Squadron Leader) Hauptmann Hans-Joachim Herrmann of 7 Staffel, III Gruppe Kampfgeschwader 30 (7th Squadron, III Group, Bomber Wing 30), piloted a Ju-88 from the Gerbini airfield in Sicily, gaining notoriety for targeting the merchant ship Clan Fraser in Piraeus harbour on 7 April at 03:15 hrs. The time-delayed explosion set off a cargo of TNT, resulting in the sinking of six additional merchant ships and numerous smaller vessels. The houses in Piraeus were shaken, and even in the Athens suburb of Psychiko, 14 km away, windows were shattered. The port suffered extensive damage in the fireball, rendering it unusable until after the German conquest. Ju 88s were also actively involved in the invasion of Crete in May 1941. Their strategic importance persisted in the Greek theatre after the Italian surrender in September 1943, where they were instrumental in the German takeover of the Italian-held Dodecanese Islands, thwarting British aspirations for an invasion in the Aegean (Operation Accolade).

The Eye of the North

The northernmost islet of the Northern Sporades, Psathoura, covers an area of 771 acres, with its highest point reaching just fourteen metres above sea level. Dominating the island since its construction in 1895, stands a 28.9 metre high stone lighthouse.

Constructed by the French company Cenerale Des Phares De L Empire Ottoman for the Ottoman Empire, the lighthouse, among thirty-one others, transitioned to Greek ownership as territories were repatriated. While inactive during WWII, it was restored to functionality in 1945 with the restoration of the lighthouse network. In 1987, its oil-burning machinery was replaced with a solar power source and full automation. Emitting a white flash every ten seconds, its beam extends up to 17 nautical miles.

Some researchers propose Psathoura as the location of ancient Eudemia, supported by scattered stonework remnants attesting to ancient habitation in Neolithic times. The island is also noteworthy for its proximity to a dormant underwater volcano and evidence of subsidence. Beneath the waves on the north side at 10 to 17 metres depth lie geological formations that resemble scattered stonework, possibly an ancient fortress.

About the authors

Vasilis Mentogiannis is the technical director of the UFR team, specialising as a commercial diver in underwater services and documentation, covering a wide range of projects from the marine construction industry to maritime cultural heritage. He is one of the co-founders of the Korseai Archaeological Institute, the founder of Hippocampus Marine Institute, and one of the designers of the uNdersea visiOn sUrveillance System (NOUS), which can be found at: nous.com.gr

Ross J. Robertson, an Advanced Open Water and Nitrox Diver, is an author and educator with a keen interest in Aegean shipwrecks and Greek WW2 history. Bringing these elements together in numerous magazine and newspaper articles, he is also the curator of this website ww2stories.org

We value your opinion!

Your feedback is important to us. If you enjoyed this article and would like to see similar content, show your appreciation by clicking the ‘Claps’ icon below. Also, ensure you stay up-to-date with our latest articles by subscribing to our Newsletter. You’ll receive new posts directly to your email inbox. Thank you for your support!

‘History has to be shared to be appreciated’

Subscribe to our Mailing List. We’ll keep you in the loop.

Footnotes

- Mavrikis, K. (1997). Upper Magnesia Islands. Alonissos.

↩︎ - Radke, S. (1990). Kampfgeschwader 54. Munich, Shield Publishing.

↩︎ - Jäger Blatt, Journal of Former Fighter Pilots Association, Frankfurt, Germany.

↩︎ - A modified Junkers Ju 88 bomber, referred to as a Mistel (German for the parasitic plant mistletoe), had its crew compartment in the nose replaced by a specially designed section filled with high explosives. Mounted on top of the bomber on struts was a single-engine fighter aircraft. The pilot in the fighter would guide the combination to the target, release the Mistel to destroy the target, and then safely return to base.

↩︎