Churchill’s ‘Monuments Men’ in Greece

Given the infamy of their ruthless subjugation and spiteful destruction, one might assume the Nazis wilfully plundered or desecrated ancient Greek artefacts and sites during WWII. However, according to official post-war reports, this was not necessarily the case. Ross J. Robertson investigates.

On the insistence of art experts, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt established a special committee in June 1943. It soon evolved into the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program – an unprecedented initiative to protect cultural property and heritage in war-torn Europe and the Far East. Although under-staffed and beset with the problems of operating close to the front line, a small but dedicated group of middle-aged historians, art directors, museum curators and the like managed to recover entire troves of priceless works of art stolen by the Nazis.

If the story sounds familiar, then you probably have the 2014 film ‘Monuments Men’ starring, amongst others, George Clooney and Cate Blanchett to thank for it. Based on the Robert M. Edsel’s 2009 book of the same name, itself inspired by Lynn H. Nicholas’ 1995 book ‘The Rape of Europa’, it portrays the singular efforts made to successfully recover works such as Van Eyck’s 15th century Ghent Altarpiece and Michelangelo’s early 16th century Madonna and Child.

Innumerable monuments, churches and works of art fell under the ‘Monuments Men’s’ purview. However, Europe’s cultural heritage spans many millennia. It abounds with ancient pre-Christian sites of archaeological importance, not to mention priceless artefacts stored in museums and private collections.

Greece in particular is rich with remnants from the Neolithic, Bronze, and Classical eras, the latter giving rise to the Hellenistic period (323 BC to 31 BC). An unequalled time in all of history, it saw the widespread emergence of art, science, mathematics, literature, rhetoric, theatre, architecture, philosophy and democracy – the enlightenments upon which the very bedrock of Western civilisation remains founded.

Such ideals were entirely incompatible with the distortions of 20th century fascist ideals. Embodied by Nuremberg rallies, book-burning and goose-stepping conquests, a dangerous mockery was made of the intellectual and liberal pursuits which the ancient Greeks had bestowed upon the world. In addition to its geographical importance, it made Greece a potential ideological target.

Irreverence came in the form of an invasion by Italian fascists in October 1940. However, Benito Mussolini’s brazen attempt to relive the past glories of the Roman Empire were quickly thwarted. The Hellenic Army managed to convincingly beat the aggressors back across the mountains and into Albania, only stopping due to the onset of heavy winter. It became the very first Allied ground victory of the war.

The reprieve offered further opportunity for custodians and curators to take precautionary measures to protect Greece’s ancient treasures. Certainly, important collections were spirited away for safekeeping. Artefacts from the Athenian Acropolis and the iconic Parthenon (438 BC) were either hidden in sealed caves on nearby Philopappos hill (close to the so-called ‘Prison of Socrates’) or stored in the deep vaults of the National Bank of Greece. Exhibits from the National Museum were placed in cellars. Elsewhere, important exhibits were buried or also hidden. At Pylos, famed home of Mycenean King Nestor, the landowner prudently ploughed over the first excavation work undertaken just a year earlier. In another case, artefacts from the Temple of Alea at Tegea were buried in sand within the local museum, right under its floor.

On the 6th of April 1941, Nazi retribution for the Italian defeat was to come swift and without mercy – and end up routing a 62,000 strong British and Commonwealth expeditionary force in the process. Code named ‘Operation Marita’, the entire Greek mainland was seized by the end of the month. The islands, including Crete, fell shortly afterwards. Control was soon divvied up between the Axis Italians and Bulgarians, with the Germans retaining all key locations for themselves. And while the ensuing subjection extracted a truly terrible human toll, the fate of Greek, and therefore Western cultural heritage, became shrouded to the outside world.

As the war turned against Hitler throughout 1943 and into 1944, the ever-shrewd Prime Minister Winston L. S. Churchill began to turn his attention to post-war matters. He appointed his own group of ‘Monuments Men’ in May 1944, just one month before D-Day and the beginnings of the reclamation of Western Europe. Given the self-explanatory name of the ‘British Committee on the Preservation and Restitution of Works of Art, Archives and Other Material in Enemy Hands’, it was to both co-operate with Roosevelt’s original team and widen its effective area of operations.

Churchill’s ‘Monuments Men’ had boots on Greek ground shortly after its October 1944 liberation. However, anything other than a cursory damage assessment soon became impossible. Having fought off the Germans at considerable cost, many Greek resistance groups, particularly the ELAS communists refused to relinquish their weapons and de facto power. By December, the situation had degraded into an all-out pitched battle for Athens. Despite the use of tanks and the RAF, the British came extraordinarily close to losing.

On Christmas day 1944, Churchill himself arrived in Greece to help conciliate the situation. But even as he prepared to mediate with the communists, an ELAS assassination plot was uncovered. Three-quarters of a ton of German explosives – all packed and fused – had been planted in the sewage pipes under the Grande Bretagne Hotel in central Athens – the agreed venue for the negotiations.

The strife in the capital eventually abated, but the country became embroiled in a bitter civil war that would last until 1949. In spite of such adverse circumstances, Churchill’s ‘Monuments Men’ still managed to file field reports in 1945 from all around the country. These were compiled by Archaeological Advisor to the War Office, Lt. Colonel Sir Leonard Woolley, who had become renowned for pioneering modern systematic methods to archaeology, in addition to spying for British Intelligence. His assistant from 1912 to 1914 was none other than Thomas E. Lawrence (aka Lawrence of Arabia). Using archeology as a cover, both spied on the German construction of the Berlin to Baghdad railway in Syria, as well as making a covert survey of the Negev Desert in Palestine for the British military. Stationed in Egypt, Woolly continued his espionage work during WWI until becoming an unfortunate prisoner of war in Turkey for two years.

Woolley’s WWII reports on Greece alleviated many fears. In his own words: “Happily, the classic monuments and sites in Athens did not suffer to any great extent during the four years of Axis occupation, while with the exception of some wanton damage committed by the Germans and the Italians in a few locations, the prehistoric sites and monuments in other parts of Greece – unlike the Byzantine ones – also survived the ordeal comparatively unscathed.”

The cover letter written by Lt. Colonel Sir Leonard Woolley on the submission of his Greek Antiquities Report.

(T-209/15 Crown Copyright ©)

Damage to archeological sites mainly came in the form of using rubble to create observation posts, fortifications and gun emplacements or digging communication trenches between positions. Both the Temple of Posidon at Sonuion (440 BC) and the Mycenaean city of Tiryns (approx. 1350 BC) are notable examples. Other forms of disruption include the Italians laying a largely inexplicable concrete slab in the orchestra area at Argos Theatre (320 BC), the Germans using a tower and adjoining wall (3 AD) at Messini as ranging and target practice for their artillery, and chips caused by German small arms fire in the only surviving example of Mycenaean monument sculpture, the famous ‘Lion Gate’ at Mycenae (approx. 1350 BC).

Ancient Olympia (approx. 700 BC) – home of the original Olympic Games – had remained largely untouched. At one stage during 1944, German tanks had assembled under the trees at the site. However, according to Woolley’s report, when a British officer formally protested, they were obligingly removed to prevent the possibility of aerial bombing and damage to excavations.

Ironically, it was the British themselves who had provoked damage to the temples and buildings found on the Athenian Acropolis. During the ELAS uprising in December 1944, they held the high ground it afforded – even overturning fragmented marble slabs to create defensive positions. Unsurprisingly, this made the site a target for rebel fire. Woolley’s report found that numerous bullet marks peppered the walls and pillars of the various structures on the site, such as the Temple of Nike. The Parthenon – by far the most culturally symbolic building of them all – had sustained small arms fire on the western side, along with two direct shell hits and several mortar bursts, causing damage to the marble floor, steps and columns. However, considering the communists had lobbed as many as 32 mortar rounds onto the area, damage was relatively light.

Elsewhere, air raids accounted for damage or loss. The buried archeological cache from the Lamia museum in Thessaly suffered a direct hit and was totally destroyed. It had consisted of some fifty inscribed stone pieces, vases and thirty-five coins. Several Minoan antiquities in the Heraklion museum on Crete were damaged during a Luftwaffe attack in May 1941. Further damage was sustained by Allied bombing in February 1944 and again in June 1944. Having been crippled during an aerial attack on June 1st 1944, the merchantman Gertrud was towed to Heraklion where it anchored in the middle of the harbour. It was struck again the next day by bombers. The resultant fire ignited the cargo of munitions onboard, blowing the vessel sky-high and causing damage to the town.

The situation at the Heraklion museum during the occupation would have been far worse, had it not been for the efforts of the Director of Antiquities on Crete, Dr. Nikolaos Platon. He had several invaluable pieces buried in the museum grounds. He also bolstered security by having a heavy metal gate installed before cramming the cellar with as many exhibits as possible. “Despite threats of execution made by the Germans, he flatly refused to surrender the key,” explained his son, Professor Eleftherios Platon, himself an Archaeologist at the University of Athens. “Moreover, he risked life and limb when he took it upon himself to sleep in the museum so as to prevent any illicit removals.”

Dr. Nikolaos Platon did much to prevent the wholesale robbery of artefacts from Crete in disregard to his personal safety.

(Platon Family Archive ©)

Incredibly, Churchill’s ‘Monuments Men’ discovered that many museums around the country had been kept more or less as they were throughout the occupation – as if rudimentary sand-bagging and an ornate front door would be enough to keep the bombs or any marauding soldiery at bay. Indeed, several museums were looted – ancient coins being a particular target of pilfering – and some completely ransacked, especially by the Italians and Bulgarians who showed considerably less constraint than the Germans.

In several locations, German archeologists carried out excavations as part of on-going work or as new initiatives. They dug at Olympia, for instance, in the summer of 1941. Sanctioned and supervised by the Greek authorities, this excavation was reported to have been carried out appropriately without any untoward removal of artefacts from the site. However, unsanctioned excavations elsewhere were far less exemplary. In the spring of 1942, one near Vergina in Central Macedonia unearthed several chamber tombs from the Hellenistic period – pottery from which was promptly handed over to German Military Command, despite later protests made by the Greek authorities.

The misappropriation of cultural artefacts was not limited to land. In 1942, famed Austrian marine biologist Hans Hass organised a scientific expedition of the Sporades archipelago in the Aegean. On board his schooner was fellow Austrian, Alfons Hochhauser. Having lived in Greece as a fisherman before the war, Hochhauser was fluent in Greek and had intimate knowledge of the area, including its archaeology. In April 1928, he and other fishermen recovered the Artemision Bronze, a life-sized statue of Zeus (or perhaps Poseidon) made around 460 BC and now a prime exhibit at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens. Hochhauser’s 1942 diary describes the real purpose of the Hass expedition: “We are the ones who took them out of the sea and they were the ones who packed them in wooden crates and put them into the hold. I have counted 12 crates so far. All of them are full of amazing artefacts from the sunken city. Some of them are like new. When I asked ‘X’ [Hass] where they were being sent, he replied somewhere more secure. He probably means the museums in Europe. I am in debt to ‘X’, so I can’t say what I really think about it.”

The Artemision Bronze (460 BC), also called the “God from the Sea,” is an ancient 2m tall Greek sculpture a found off Cape Artemision, Greece. It may represent Zeus, although some suggest it could be Poseidon.

(Author’s Archive ©)

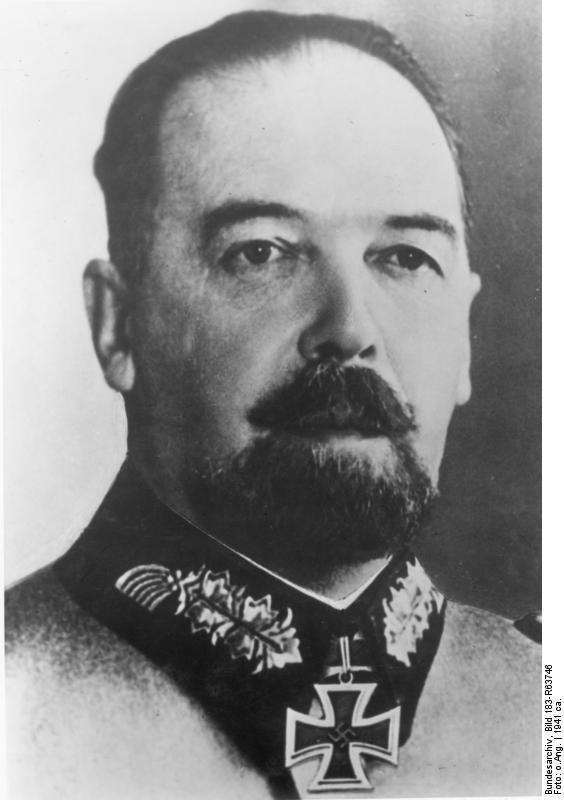

This pales into insignificance when compared to events on Crete. As commander of the 5th Mountain Division, General Julius Ringel had been instrumental in the April 1941 conquest of the Greek mainland and the ensuing fall of Crete in May. Even as his troops extracted brutal revenge on local civilians for aiding the Allies during the German invasion, he was awarded the Knight’s Cross in June and made Commandant of the entire island.

He almost immediately took up residence at the Villa Ariadne, former home of famed archeologist Sir Arthur Evans and centrepiece of the British School at Athens Knossos Research Centre since Evans had endowed it in 1926. Back in 1900, Evans had discovered the nearby Palace of Knossos, thereby revealing the existence of the Minoan civilization to the world (a name he coined based on the story of the Minotaur in Greek Mythology).

Of Ringel, Woolley reports that “He looked on the antiquities in the Villa as his personal property.” When Dr. Nikolaos Platon heard of the General’s frequent visits to Knossos and his demands for the keys to the on-site Stratigraphic Museum, where artefacts from the Palace were sorted and stored by archeologists, he immediately wrote letters of protest. “He even travelled to Knossos to confront him,” said Professor Platon. “However, as my father’s notes testify, Ringel arrogantly pretended not to even notice his presence.”

General Julius Ringel. Notorious for reprisals against civilians who resisted the German invasion and subsequently pillaging priceless Cretan archaeological treasures.

(Bundesarchiv 183-R63746 ©)

Despite further protests from fellow German officers of the Referat für Kunstschutz (Department of Art Protection), Ringel raided the Stratigraphic Museum wholesale. He also had an illicit excavation undertaken first by the common soldiery and then by POWs in the hope of uncovering more treasures. The dig was a failure, but by the autumn of 1941, he had appropriated more than enough booty to send an impressive collection back home to Austria by air. Although some of the spoils were retrieved in September 1948, it was not until as recently as 2017 that twenty-six artefacts were repatriated at the instigation of the Austrian University of Graz. Many others are still missing to this day.

Ringel was eventually transferred to the Eastern front in March 1942 where he was further promoted and decorated. In 1943, he was fighting the Allied invasion of Italy. His career continued to flourish to the point of commanding his own ‘Army Corps Ringel’ in Salzburg until Germany’s surrender in 1945. He was never held accountable for his thievery or brutality. Rather, he died in the idyllic Bavarian countryside in 1969 at the respectable age of 77.

Fortunately, Crete was one of the few exceptions. As Woolley reports, “Germans, on the whole, abstained from looting on any very large scale.” The Nazis may have systematically laid waste to entire villages and towns, turning a million Greeks out of their homes and making them refugees in their own country, but constraint was definitely shown when it came to the country’s cultural riches.

The reasons can only be guessed at. Was it recognition of the sanctity of the past? Or was it that unlike the hordes of Renaissance art stolen from central Europe, Hitler had no desire to add an antiquity wing to his planned Führermuseum in his hometown of Linz in Austria? Whatever the reason, Churchill clearly realised the importance of archaeological preservation and tried to do something about it. It is indeed fortunate for posterity that most sites and artefacts remained unmolested. A fittingly respectful circumstance, seeing it was the Greeks who gave us the word ‘archaeology’ in the first place.

Ref: T-209-15 UK National Archives, Kew.