Solferino/TA-18

The full version of this article entitled ‘Running the Gauntlet’ was published in the October 2021 issue of Britain at War magazine, Key Publishing, UK.

As Nazi forces hastily withdraw from Greece in October 1944, a high-stakes mercy mission to rescue marooned Kriegsmarine sailors clashes with cutting-edge Allied radar tech. Ross J. Robertson investigates the story.

In the shadowy confines of the Royal Navy T-class destroyer, HMS Tuscan (R56),1a ghostly phosphorescent glow emanated from a 9-inch circular CRT display, casting an eerie light on the face of a radar operator. This display, with its circular sweep tracking the Greek coastline six nautical miles to the southwest, held an unprecedented technological advantage – the ability to ‘see’ distant objects, come rain or shine.

Each sweep chased the fading glow of its predecessor as it tirelessly searched for prey. A faint blip suddenly materialised about a mile off the shoreline, barely registering on the radar. It gained strength with each successive sweep but left only a fleeting trace. The radar operator hesitated, questioning whether this was just another false echo or if he had made the correct frequency adjustments. By the third sweep, the trace had solidified into a clear contact at bearing 274° and a distance of 5 nautical miles. The time was 22:25 hrs.

Outside in the darkness made heavy by an impervious blanket of clouds, companion destroyer HMS Termagant (R89)2 sailed under the command of formidable Lt Cmdr Jack Scatchard, affectionately known as ‘Black Jack’ by his crew for his uncompromising approach.3 With their sleek forms cutting through the dark Aegean waters, both destroyers were on a mission to intercept any enemy vessels that dared venture into their designated hunting ground.

It was 19 October 1944, and the German forces were in a hasty retreat, leaving behind a power vacuum in their wake. Athens had been liberated a week earlier, and British forces, operating under the mandate of ‘Operation Manna,’ were gradually advancing northward. While most Greek resistance groups were motivated by a desire for retribution against the Germans, their primary concern was either gaining control of the country for themselves or stopping other resistance groups from doing so. This internal power struggle, which would eventually escalate into an all-out civil war lasting until 1949, had been a persistent issue throughout much of the occupation and was now inadvertently facilitating the German escape.

The predominant concern among German soldiers, airmen, and sailors had less to do with the Greek resistance or the British forces and more to do with the very real danger of being trapped in Greece. With Romania and Bulgaria already succumbing to the advancing Russian forces, they harboured deep apprehension about the prospect of being unable to return to Germany before the passage through the Balkans was sealed off. It was widely acknowledged that the Red Army showed no quarter, so being cut off and made vulnerable was to be avoided.

Mission of Mercy

Source: Nikolas Sidiropoulos Archive ©

In these circumstances, Lt Günther-Werner Schmidt led the Kriegsmarine torpedo boat TA-18 (formerly the Royal Italian Navy destroyer Solferino of the Palestro-class)4 on a perilous mission for a noble cause. Having departed from Thessaloniki, TA-18 now raced to rescue marooned shipwreck survivors.

On 18 October, the Kriegsmarine minesweepers GA-73 and GA-76 (formerly R-17 and R-159 of the Royal Italian Navy) had met their demise at the hands of Allied aircraft. This incident occurred near the small island of Argyronisos, situated to the north of Euboea (also spelt Evia) and near the entrance of Trikeri Channel (leading to the Pagasitikos Gulf and the town of Volos – known as Volos Bay to the Germans). A group of some 80 to 100 survivors found themselves stranded on the uninhabited island, their urgent need for assistance evident. While most other Kriegsmarine vessels had already evacuated north, Lt Schmidt and his 132 officers and crew had been sent back down south on a route fraught with danger. Their only real ally was the cover of darkness.

Source: Nikolas Sidiropoulos Archive ©

Source: Nikolas Sidiropoulos Archive ©

Unbeknownst to those aboard TA-18, Lt Cmdr Scatchard received the radar contact report from HMS Tuscan. Despite being on the very northern edge of his patrol area at 39°26′ N, 26°16′ E, he adjusted his course to intercept the potential target, a decision that would alter the course of the night and change the fate of many.

Relying on radar tracking, by 22:41 hrs the destroyers had positioned themselves 5,000 metres from TA-18, effectively pinning the target against the coastline. The Type 291 and 272 radar sets on-board could be used in a ‘blind-fire’ attack, with gun fire trajectory being solely guided by radar tracking information. However, protocol demanded visual confirmation before their deadly arsenal could be unleashed. Raising his binoculars in anticipation, Lt Cmdr Scatchard and issued a command to Fire Control.

Radar on HMS Termagant and HMS Tuscan: Type 272 Radar: First developed in 1941, Type 272 Radar was 'centimetric' (S-band) with a 10 cm wavelength, 5 kW of power, operating at a frequency of approx 3,000 Mhz. It was principally used to detect surface threats. Centimetric radar was based on the development of the cavity magnetron, a revolutionary device which could generate a high power signal at short wavelengths, thereby improving performance and allowing for smaller, lighter antennas more suited to smaller vessels in the fleet. Type 272 Radar used paraboloid 'Cheese antennas', so called as they resembled a section cut from a cheese wheel - which allowed a focused, narrow beam to be kept on a surface target and a return signal, despite the susceptibility of destroyers and smaller vessels to pitch and roll. On RN destroyers, they were housed in a perspex radome some 16 metres above the waterline, with control by a manual crack linked to the antenna by a Bowden cable. Rotation was limited to a 200° sweep, leaving an aft blindspot of 160°. They were capable of detecting a surfaced submarine at 6 or 7,000 metres. Type 291 Radar: Based on the rapid technological improvements made in radar technology, particularly with micropup values which allowed greater output power, Type 291 was 'small metric' with a 1.5m wavelength, 100 kW power, operating at a frequency of 214 Mhz. It was a combined warning set used to detect both surface and air threats, but the surface role was often supplemented with a centimetic set (i.e. the Type 272s on the HMS Termagant and HMS Tuscan). Type 291 was a culmination of the development of Type 286 and a replacement for Type 290. Installation on RN and Commonwealth destroyers and smaller vessels such as MTBs began in late 1942, to become ubiquitous by the end of the war. The Type 291W variant was even installed on some submarines. While earlier sets had manual crack handles, these were soon replaced by a autonomous rotating antenna on a light-weight aluminium pedestal. By mid 1943, PPI (Plan Position Indicator) displays developed and produced for the navy by EMI were used. These had an afterglow 9 inch CRT (Cathode Ray Tube) with an internal magnetic coil mechanically rotated in sync with the antenna, producing a rotating sweepline on the display. With the ship's position represented in the middle of a calibrated display, PPIs facilitated air and and surface warning, along with plotting functionality.

Starshells exploded above TA-18, exposing the hapless vessel with their cruel brilliance. Lt Schmidt immediately ordered full speed ahead to evade the threat that seemed to come from nowhere. Meanwhile, on the bridge of HMS Termagant, the TA-18 was positively identified as the enemy.

Lt Cmdr Scatchard’s order was: ‘Engage!’

The British destroyers began a relentless pounding with their 4.7 inch (120 mm) guns.5 A cat-and-mouse chase ensued with the TA-18 attempting evasive manoeuvres in a desperate bid to shake off its attackers. Continuous fire rang out, the night air filled with tension and the acrid scent of cordite and battle.

“We fired so many shells at it that we had to stop twice to empty the turret floors of all the empty shell casings.”

Despite the increasing damage inflicted on TA-18 in the chaos, Lt Schmidt did his utmost to turn the tide of this perilous encounter. He fired several salvos at HMS Tuscan, but it remained miraculously untouched. He even managed to launch a torpedo. However, fate intervened once more. It had a gyro malfunction and ended up circling uselessly in the water.

Ordnance from the British destroyers continued unabated. Ensign Spyridon Kapsalis, a Greek who was one of the gunners in the aft turret on HMS Termagant recalls; “We fired so many shells at it that we had to stop twice to empty the turret floors of all the empty shell casings.” 6

Source: ADM199/845/1 Photo taken by Platon Alexiadis ©

At 22:50 hrs, one of Lt Schmidt’s officers reported all hands killed in boiler room No. 3. Incessant explosions racked the ship. Fires erupted, blinding smoke billowed, and the crew were in disarray. Their only hope of escaping the ceaseless barrage was to head for shore and abandon ship.

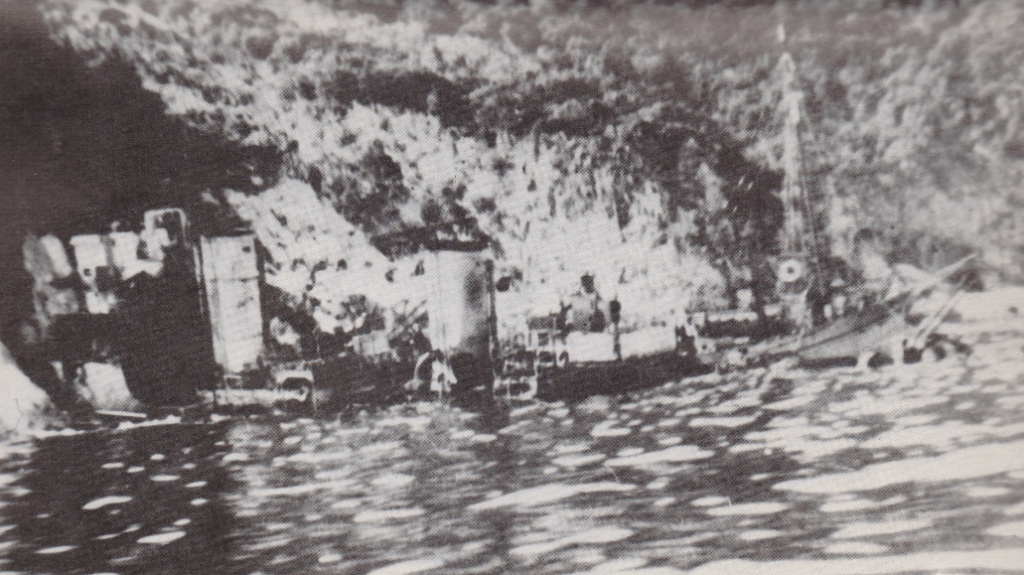

No one knows whether what happened next was deliberate or if control of the ship had been lost. Instead of grounding on a sandy beach or slowing down for crew evacuation, TA-18 crashed headlong at full speed into the shore with a deafening screech, throwing the crew in all directions. Somehow, its bow slammed into a cave, wedging itself in the entrance. The rest of the ship was left grounded in the shallow water, still ablaze and billowing smoke.

At 22:55 hrs, the British lost contact with TA-18 as it ran aground and its radar return merged with that of the coastal terrain. The ever tenacious Lt Cmdr Scatchard was not going to let the matter go so lightly, so he ordered the destroyers turn back for another pass along the shore. So many shells were fired at the stricken vessel from 23:01 until 23:30 hrs that Lt Cmdr Scatchard described the final phase of the attack in his report as ‘Operation Plaster’.

The British destroyers eventually ceased fire, leaving the burning TA-18 wrecked and its crew stranded. A staggering 161 starshells and 493 high-explosive shells had been unleashed in the engagement. Yet, Lt. Schmidt and as many as 110 of his crew had managed to cling to life, eventually seeking refuge on the unforgiving rocky cliffs and enduring the onslaught.

Even after the British destroyers retired, the ordeal was far from over. The TA-18 had run around at Paliokastro, just a short distance away from Agios Ioannis (St. John’s) on the Aegean side of the Pelion peninsular where Cmdr Solon Katafygiotis led the 4th Squadron of the Communist-oriented Hellenic Liberation Navy (ELAN).7 They had witnessed the battle and now approached the scene, ready to demonstrate their own brand of respect for the hated occupiers.

“We started rounding them up and killed three or four,

but they resisted.”

They arrived on two boats, while another group approached by land. Cmdr Katafygiotis describes the event: “We called on the Germans to surrender over a megaphone. The Germans did not give themselves up. A fierce fight began in the early hours of the morning. After several hours, they began to surrender little by little in intervals.” 8 Shore party leader Stathis Alexiou is more explicit and succinct in the retelling: “We started rounding them up and killed three or four, but they resisted.” Compatriot Nikos Markou states “[some Germans] took their rubber dinghy and made for open the sea in the hope of being saved by their own boats. But they were surrounded by three (sic) of our boats, neutralised and taken prisoner.” 9

With ten seriously injured, limited ammunition and no realistic chance of rescue, their options were rapidly dwindling in the face of circumstance. Consequently, Lt Schmidt and most of his men were compelled to lay down their arms. However, a small group of Germans remained positioned behind a large-calibre anti-aircraft gun on the TA-18. Now a prisoner, Lt Schmidt was dispatched alongside the TA-18 by boat to engage in dialogue with them, but they adamantly refused to surrender. “As time went on, their resistance began to wane. Finally, at dusk, the last of the Germans yielded,” Cmdr Katafygiotis concluded.

Source: Koliou, N. (1985) 'Unknown Aspects of the Occupation and the Resistance.' Volos: Self-published

The surrender sealed their fate. While the injured were transported by pack animals to the nearby mountain village of Tsagarada for medical care, the remaining survivors eventually found themselves enduring the harsh conditions of an internment camp outside the city of Larissa. Lt Schmidt and the First Engineer were forced to join a work detail and are said to have lost their lives while clearing landmines.10 Some others managed to escape, while the remainder were later transported to a prisoner of war camp in Egypt after British forces liberated Greece. The precise number of TA-18 personnel who survived the naval battle, shipwreck, capture, mistreatment, transportation, and imprisonment remains unknown to this day.

Source: Farhad Vladi ©

Those marooned on the island of Argyronisos were left abandoned. Plans for a second rescue attempt were made, but in the confusion of the mass withdrawal, they never materialised. On 24 October, the German Admiralty in the Aegean felt compelled to send a direct message to the British Naval Administration, pleading for mercy: “On the island of Argyronisos (39°00′ N 23°04′ E), there are approximately 100 German shipwreck survivors who are at significant risk of starvation. Please arrange for their immediate rescue.” [see Kriesmarine Records below] The British consented, but before they could mount an operation, ELAN arrived on the island and apprehended whoever remained. As no administrative records were kept, the precise fate of these individuals remains shrouded in uncertainty, although it is likely to have paralleled that of the TA-18’s officers and crew.

In recognition of his contributions to clearing the Aegean of the enemy,11 Lt Cdmr Scatchard received his third DSC (Distinguished Service Cross). Subsequently, he advanced to the rank of Vice Admiral and assumed the role of Flag Officer Second-in-Command of the Far East Fleet in 1962. His illustrious career culminated in retirement in 1964, having been awarded a CB, three DSCs, and Two Bars after an impressive 41 years of dedicated and distinguished service.

The wreck today

Local wreck enthusiasts have long puzzled over the TA-18’s mysterious disappearance from the coastline at Paliokastro, despite clear evidence in the archives of it having run aground so dramatically. Unlike many wrecks handled by the official Greek post-war Shipwreck Lifting Organization (OAN), the TA-18 remained conspicuously absent in their documentation. Its whereabouts remained a riddle.

However, investigations by the Underwater Survey Team (UST) unravelled this enigma. The UST, affiliated with the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and led by Dr. Kimon Papadimitriou, is a voluntary group of professionals dedicated to locating and identifying shipwrecks from the 19th and 20th centuries in Greek waters (www.wreckhistory.com).

They recognised that, with the TA-18’s bow firmly wedged inside the cave, its stability became contingent on the ebb and flow of tide levels. This induced fluctuating vertical pressure on the keel and the ribbed structure of the hull. Furthermore, the sideways movement of swirling waves, particularly during winter tempests, caused the hull to sway. Over time, this combined vertical and lateral motion gradually liberated the wreck from its partial entrapment. Astonishingly, the hull’s robustness allowed the TA-18 to stay partially afloat as it was carried away from the shoreline, eventually settling nearby, only to be torn apart by wind, wave and weather.

At present, only small and indistinct remnants stretch across a 150-metre expanse, mirroring the coastline, as if the vessel tenaciously clung to its southward mission but ultimately disintegrated along the way. Scattered fragments of the hull and tangible artefacts, such as sturdy iron bollards, winch gears, boilers, and propellers, either remain concealed in the area’s shifting sands or have gone missing. Intriguingly, modern tools like magnetometers or ground-penetrating radar hold the potential to eventually unearth any remaining pieces.

Even if that day never happens, this narrative already stands as a striking testament to those who fought amidst the darkness and tribulations of war. Ironically, in their valiant attempt to rescue marooned comrades, the rescuers themselves became shipwrecked and stranded. Meanwhile, the Royal Navy and Greek resistance, totally oblivious to the true humanitarian nature of the Kriegsmarine mission, saw it as an opportunity to help liberate occupied lands from what they rightly perceived as a ruthlessly implacable and unforgiving enemy.

It is also a tale distinguished by the fact that it was the very last naval battle of World War II in the Aegean Sea. As with this and many other stories, it was theatre where expectations often clashed dramatically with the actual unfolding of events.

Acknowledgements: The author wishes to extend special thanks to Nikolas Sidiropoulos and Aris Bilalis for their help in the development of the original version of this article. Gratitude also extended to Platon Alexiades for his inexhaustible kindness in all matters pertaining to WWII wrecks in Greek waters.

Delve Deeper

The following footnotes and references offer a richer context to the story.

Shipography

Royal Navy T-class destroyers (1,758 ton): Eight T-class destroyers were built during the war under the 6th Emergency Flotilla programme, with all being completed between 1942 and 1943. They principally served as fleet and convoy escorts. Dimensions: length 110 m, beam 10.9, draught 4.3 m. They were powered by Parsons geared turbines, two shafts delivering 40,000 hp and a maximum speed of 36.7 knots. Complement: typically 180 to 225 men. Standard armament: Four 4.7-inch (120 mm) QF Mk IX guns, two 40mm Bofors, eight QF 20 mm Oerlikon anti-aircraft guns, and eight 21 inch (30 cm) torpedo tubes.

Italian Palestro-class destroyers (1,045 ton): Based on the Audace-class destroyer, eight ships of the Palestra class were ordered during WWI but only four were ever built. These were laid down in 1917 but not completed until 1921 to 1923. Superseded by more modern destroyers, they were downgraded to torpedo boat status in 1938. Dimensions: length 81.9 m, beam 8.0 m, draught 2.7 m. They were powered by twin Zoelly steam turbines, two shafts delivering 18,000 hp and a maximum speed of 32 knots. Complement: typically 118 men. Armament (original configuration): four Schneider-Armstrong (1917 model) 102/45 mm (4 inch) guns, two Ansaldo 76/40 mm (3 inch) guns, two 6.5/80 mm guns, four 450 mm (18 inch) torpedo tubes. They typically carried between 10 to 38 mines.

Kreigsmarine Records

The movements of T-18 were tracked by the War Diary of the German Naval Staff Operations Division12, even as the Admiral, Aegean and his Staff were being evacuated north to Vienna. They arrived on 26 October 1944.13

CONFIDENTIAL

[Captured diary translated after the war into English]

18 Oct. 1944: The evacuation of Volos has been planned for the night of 18 Oct. The remaining coastal vessels and the ready to move auxiliary sailing vessels have put to sea for Salonika on 18 Oct. Two motor minesweepers and the torpedo boat TA “18” have been sent as escort vessels. [p 400]

19 Oct. 1944: Due to a breakdown of the radio connection, the hauling of ship-wrecked from the island-exit in the Volos Bay, which was planned for 18 Oct., has not been carried out. The operation is to be repeated the following night with the torpedo boat TA “18”. [p 421]

20 Oct. 1944: No report has been received so far on the transfer of the ship-wrecked by the torpedo boat TA “18”. [p 441]

21 Oct. 1944: The search for the torpedo boat TA “I8” remained unsuccessful. [p 460]

22 Oct. 1944: The torpedo boat TA “18” has been overdue since the night of 19 Oct. The boat was to rescue shipwrecked from an island in the exit of the Volos Bay. The British broadcast reported that two British destroyers had sunk a German destroyer near Salonika on 19 Oct. In the opinion of the Commanding Admiral, Aegean, the reason for the loss of the torpedo boat TA “I8” is probably to be seen in a mine hit. [p 477]

23 Oct. 1944: The last attempt of rescuing the shipwrecked on the island in the Volos Bay turned out unsuccessfully due to continuous breakdowns of the engines in the combined operations assault boats. [p 496]

25 Oct. 1944: The Commanding Admiral, Aegean has asked the British Commander in Chief, Eastern Mediterranean by a radio message to pick up the shipwrecked from the islands in the Volos Bay. The radio message was acknowledged by the British. At 08:53, Alexandria issued an order to the British warships for assistance. [p 530]

Footnotes

- The HMS Tuscan (R56) was one of eight British T-class destroyers [see Shipography above] of the 6th Emergency Flotilla built under the War Emergency Programme. It was laid down on 06 August 1941 at Swan Hunter & Wigham Richardson Ltd. Shipyards, Wallsend, UK, launched on 28 May 1942 and completed on 11 March 43. After sea trials, it was deployed in convoy defence and fleet screening roles. It struct a floating mine in Bristol channel on 14 May 1943 with no loss of crew. After repairs, it was sent to the Mediterranean and conducted Type 276 (surface and low-air warning) radar development trials in November 1943. It operated in the Adriatic and central Mediterranean region until taking part in Operation Dragoon (the Allied invasion of the South of France on 15 August 1944) with seven other T-class destroyers, including the HMS Termagant. In September 1944, it was assigned to the Aegean. On 13 September 1944 it sank cargo steamer SS Toni (638 tons) with HMS Troubridge (R00). Working with HMS Termagant, it sank patrol vessels GK-32 and GK-62 (former Greek fishing boats) and torpedo boat TA-37 (1,118 tons) south-west of Cape Kassandra on 07 October 1944. Contrary to some reports, it failed to sink submarine chaser UJ2102 at the time (see footnote 11]). On 19 October 1944 it sank torpedo boat TA-18 with HMS Termagant on the west coast of the Greek Pelion peninsular (present story). In December 1944, it intercepted and sank two landing craft with HMS Kelvin (F37) (see picture above) off Rhodes. After returning to the UK for a refit, it was sent to the Pacific theatre in 1945, its pennant changing to D51 to comply with American nomenclature. Postwar, it was refitted twice and served as a reserve ship based in British ports to be eventually scrapped in Bo’ness, Scotland in 1966. The ship’s motto was ‘I hold what I take’.

↩︎ - The HMS Termagant (R89) was one of the 6th Emergency Flotilla’s eight British T-class destroyers [see Shipography above] built under the War Emergency Programme. It was laid down on 25 November 1941 at William Denny & Bros. Shipyards at Dumbarton, UK, launched on 22 March 1943 and completed on 18 October 43. After sea trials, it was despatched to the Mediterranean with five other T-class destroyers in December 1943 to operate in the western and central Mediterranean region. After U-453 (Cmdr, Lt Dierk Lührs) sank the British cargo steamer SS Fort Missanabie (7,147 tons) off Cape Spartivento, Italy on 19 May 1944, HMS Tuscan with destroyers HMS Liddesdale (L100) and HMS Tenacious (R45) retaliated with depth charges before losing contact. The U-boat was relocated the following morning and subjected to a twelve-hour depth charge attack from all three British vessels, eventually forcing it to the surface to surrender.

In August 1944, the HMS Termagant took part in the invasion of southern France (Operation Dragoon) with seven other T-class destroyers, including the HMS Tuscan. In September 1944, it was assigned to the Aegean

theatre to impede the German evacuation of the islands. Together with destroyer HMS Terpsichore (R33), it sank five craft carrying troops on 29 September 1944. On the 16 October 1944 it sank a Siebel Ferry. Working with HMS Termagant, it sank patrol vessels GK-32 and GK-62 (former Greek fishing boats) and torpedo boat TA-37 (1,118 tons) south-west of Cape Kassandra on 7 October 1944. Contrary to some reports, it failed to sink submarine chaser UJ2102 at the time (see footnote 11). On 19 October 1944 it sank torpedo boat TA-18 (1,045 tons) with HMS Termagant on the west coast of the Pelion peninsular (present story). In January 1945, it was in Malta for a refit and preparation to be deployed in the Pacific. It sailed to Sydney, Australia and joined the Pacific British Fleet in April (with its pennant changed to D47). It took part in operations around the Sakishima Gunto islands (Operation Iceberg), Guam, and Truk (Operation Inmate). It provided fleet support during carrier attacks on Tokyo, Ykohamma, and North Honshu. On 31 August 1945 it was in Tokyo Bay to attend the formal Japanese surrender. Postwar, it returned to the UK in late 1945 and was placed in reserve. In 1952 it was refitted as an anti-submarine frigate (Type 16). It was decommissioned in 1965 to be broken up for scrap at Dalmuir on the Clyde. The ship’s motto was ‘Untameable’.

↩︎ - Lt. Cmdr. Jack Percival Scatchard, RN joined the Royal Navy as a probationer in 1923 at 13 years of age. He was First Lieutenant on the destroyer HMS Kasmir (F12) (1,720 tons) when it was bombed and sunk by Luftwaffe Ju87 ‘Stuka’ dive bombers of the STG-2 (Sturzkampfgeschwader-2) off the southern coast of Crete on 23 May 1941. He was given command of the HMS Termagant (R89) in late 1943. His post-war career flourished to the point of becoming Flag Officer Second-in-Command of the Far East Fleet in 1962. He achieved the rank of Vice Admiral and was decoratred with a C.B., three D.S.C.s and Two Bars during the entirety of his long service. He retired in 1964 and died in 2001.

↩︎ - TA-18 was formerly the Solferino of the Regia Marina (Royal Italian Navy). Laid down at Fratelli Orlando Shipyards at Livorno, Italy in 1917 but not completed until 1921 due to war shortages, it was originally classified as a destroyer (Palestro class) [see Shipography above] but would be reclassified as a torpedo boat in the late 1930’s due to its light armament in relation to more modern destroyers of the time. With the capitulation of the Italians in September 1943, it was commandeered while in the Port of Souda, Crete on 09.09.43 and became part of the newly formed Kriegsmarine 9th Torpedo Boat Flotilla (9th Torpedobootsflottille). This comprised all nine former Italian torpedo boats taken by the Germans in Greece, each of which was designated the prefix TA, an acronym standing for Torpedoboot Ausland (a Foreign Torpedo Boat). Shortly afterwards, it was mothballed in Piraeus and partially cannibalised for parts. However, a dearth of vessels caused by Allied attacks created the need to press anything suitable into service. After restoration work was hastily undertaken, the TA-18 was recommissioned on 31 August 1944.

↩︎ - The HMS Termagant and HMS Tuscan were armed with four 4.7-inch (120-mm) QF Mk IX guns mounted in separate turrets, fore and aft. Firing rate was 15 rounds a minute and maximum range 15,500 metres. Muzzle velocity was 810 metres a second. T-class destroyers were also equipped with two 40 mm Bofors, eight 20 mm anti-aircraft guns, and eight 21-inch (53.3 cm) torpedo tubes.

↩︎ - Quotation from ‘World War II – Navy Warriors Remember…’ by Anastasios K. Dimitrakopoulos, Maritime Museum of Greece.

↩︎ - Fundamentally a coastal auxiliary force, the ELAN (Greek People’s Liberation Navy or Ελληνικό Λαϊκό Απελευθερωτικό Ναυτικό) was controlled by the communist resistance movement, ELAS (Greek People’s Liberation Army or Ελληνικός Λαϊκός Απελευθερωτικός Στρατός). By 1944, its 1,200 strong resistance fighters operated a fleet of approximately 100 small sailing craft (caiques) and similar vessels around strategic areas of the Greek mainland and islands.

↩︎ - In interviews conducted in 2008 by A. Dimitrakopoulos, the then 88-year old Cmdr Solon Katafygiotis stated that he was aboard one of the two boats and that only the German Captain and the Third Engineer gave themselves up after their surrender had been called for. He said that the others boarded the torpedo boat again. However, it is thought that the majority of the crew surrendered along with their commander.

↩︎ - Quotations from ‘Unknown Aspects of Occupation and Resistance 1941-1944’ by Nitsa Koliou. Volume II, 1985. Private Edition.

↩︎ - ‘In a Losing Position: The 9th Torpedo Boat Flotilla Birnbaum’ (‘Verlorenem Posten: Die 9. Torpedobootflottillen Birnbaum’) by Friedrich-Karl, 1987.

↩︎ - Earlier in the month, on 7 October, just a day after being given operational command of the HMS Tuscan and HMS Termagant, Lt Cmdr Scatchard had sighted and sunk two auxiliary vessels off the Cape Kassandra. Shortly afterwards, at 01.30 hrs, a new target was identified. Within 30 minutes the torpedo boat TA-37 (ex Gladio) (757 tons) had been hunted down and sunk 8 nautical miles off shore. Yet another target was soon identified, and the destroyers opened fire. In a scenario similar to the one which would lead to the demise of TA-18 twelve days later, the target headed for the coast. Assisted by radar, the destroyers continued firing until their target was deemed to have run aground. To mitigate the risk of coastal artillery attack or inadvertently running into a minefield, the destroyers then disengaged and departed the area. This last target has always been assumed to be Kriegsmarine submarine chaser UJ.2102 (ex Birgitta of the Royal Hellenic Navy), a vessel assigned to the 21st Antisubmarine Flotilla (21st U-Bootjagdflottille) and famed for sinking the Greek submarine RHS Triton (Y5) (Lt Cmdr E. Kontoyiannis) off Kafirea, south-east Euboea on 16 November 1942. In fact, it had escaped the 7 October 1944 encounter with the British destroyers, only to end up being a casualty of an air raid undertaken by Ventura bombers of the 25th Squadron of the South African Air Force (SAAF) on the Port of Volos on 13 October 1944.

↩︎ - German Naval Staff Operations Division. War Diary. Part 1, Vol. 64, October 1944. Washington, D.C.: Office of Naval Intelligence, 1948-1955. ↩︎

- ibid. p 548 ↩︎

References & Sources

Admiralty Report: ADM199-845

Jack Scatchard: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2001/jul/12/guardianobituaries

‘The Applications of RADAR and Other Electronic Equipment in the Royal Navy in WWII,’ Naval Radar Trust. Edited by F.A. Kingsley. Macmillan Press Ltd. 1995.

‘The Developments of RADAR equipment for the Royal Navy 1935-45,’ Naval Radar Trust. Edited by F.A. Kingsley. Macmillan Press Ltd. 1995.

‘RADAR at Sea; The Royal Navy in WWII’ by Derek Howse, Naval Radar Trust. Macmillan Press Ltd. 1993.