This article first appeared in the September 2020 issue of DIVER Magazine (Eaton Publications, UK).

One of very few NAZI U-boats accessible to divers, Dimitri Galon and Ross J. Robertson investigate the story and current circumstance of U-133.

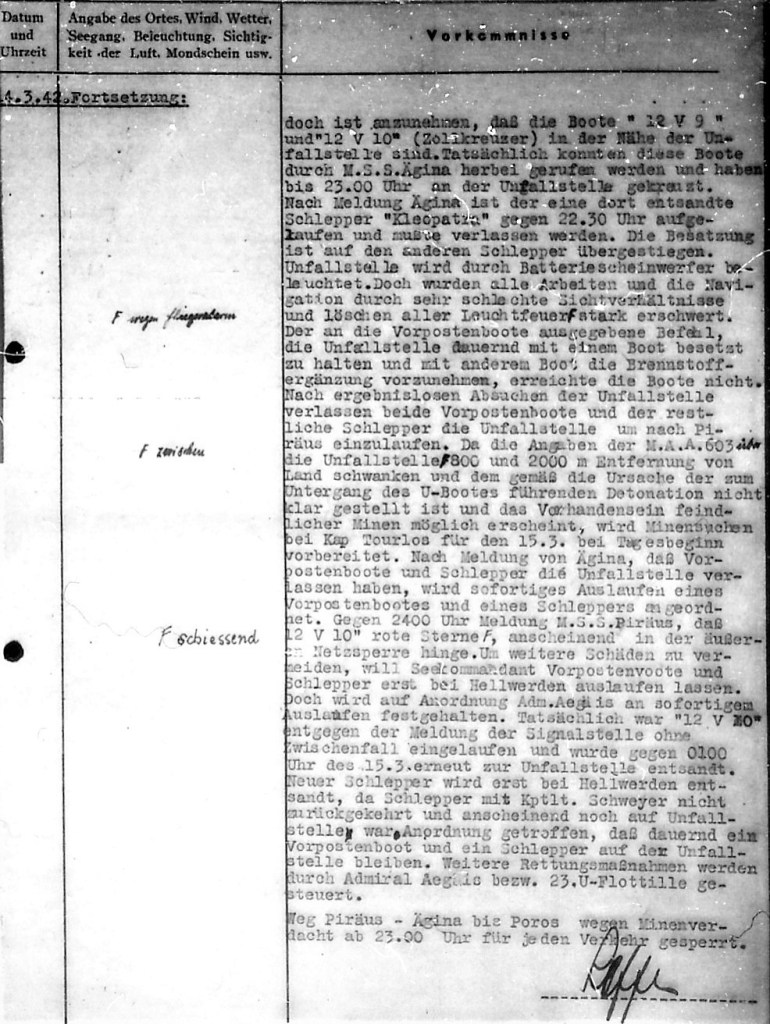

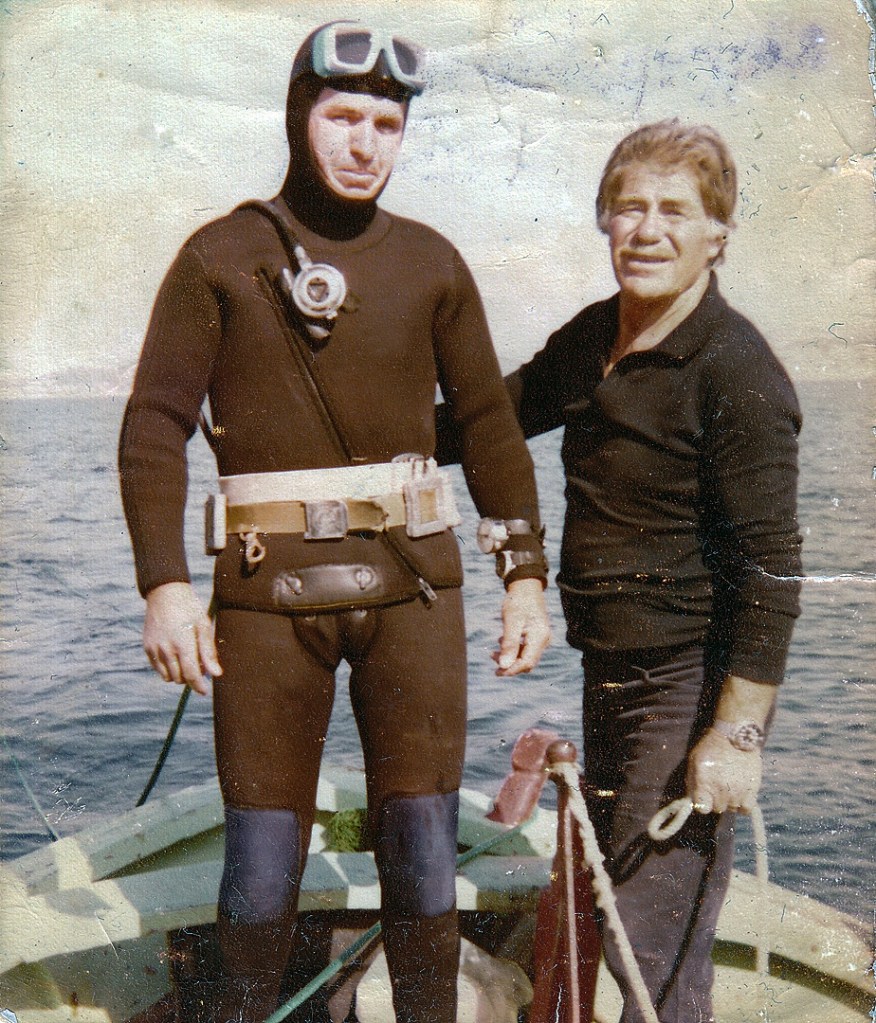

It is 1986. Professional diver Stathis Baramatis splashes into Greek waters and starts a long exploratory dive. The bright sapphire colours soon darken into ever-deepening blue hues as he continues his decent into the abyss. Survival entirely depends on a trailing umbilical and the air it supplies from the surface.

Despite the restricted view from his mask, he is trying to follow a stream of sporadic air bubbles and slowly ascending blobs of thick dark yellow oil. Curiosity has brought he and fellow diver Theophilos Klimis back to this spot – by chance they noticed an oil slick pooling on the surface only yesterday. Their years of experience suggested that the undetermined source had to be a shipwreck. While junk bonds and conspicuous lifestyles characterise the 80s yuppie era elsewhere, sponge diving and the occasional commissioned recovery dive are how Stathis and Theophilos barely eke out a living. The scrap metal riches they might extract from the new find could be considerable.

Professional divers Efstathios “Stathis” Baramatis (left) and Theophilos Klimis (right) were the ones who discovered the wreck in 1986. Efstathios Baramatis was the first person to dive and see the wreck post-war, 44 years after it sank. Source: Efstathios Baramatis ©

Twenty fathoms, twenty-five fathoms – Stathis plummets further. Being well below the thermocline, it is increasingly cold and foreboding. Visibility is poor as suspended particles whoosh by in the strong current. Nothing particularly alarming for such a seasoned diver, but he remains prudently respectful of his surroundings. He presses on. A long, cigar-like form in the eerie gloom can now be discerned. He has not come in vain. At thirty-nine fathoms – a little over seventy metres – he finally reaches the wreck. Heavily encrusted with barnacles and flourishing marine life, it is frustratingly difficult to determine exactly what he has found. It is not just the poor visibility and the gloom, much of the prize is obscured by the recent addition of an entangled fishing net.

As he would later learn, a trawler had snagged on something in exactly the same location just a day or two earlier. Despite repeated attempts to break free, the net and tackle had refused to budge. When blobs of oil unexpectedly appeared on the surface, it was realised that something in the deep had been unwittingly disturbed. Fearing trouble from the authorities and the heavy fines that might be imposed, the fishermen quickly cut the net and fled.

Almost impossibly, Stathis now finds himself gazing directly at the source of the disturbance less than forty-eight hours later. The marine encrustations, corals and sponges tell him that it is made of metal and that it sank some time ago. However, he remains completely oblivious to what type of wreck it is. He resolves to learn as much as he can with the limited bottom time available.

“I was truly mystified,” Stathis recounts. “The bow seemed to be missing and there was something like a turret which rose up from the hull, so I went to investigate. Behind it, I was eventually able to made out the barrel of a machine gun – this was the very moment I realised it must be a submarine,” Stathis explains. “My heart skipped a beat as my thoughts immediately went to her crew – submarines rarely sink without them and it immediately changed my prospective.”

After decompression (just 30-35 minutes after a 25 minute bottom time at +70 metres – incredibly, such DC (decompression) times which are way off modern dive tables and charts were routine for him), Stathis surfaces and excitedly recounts his findings to his long-time friend, Theophilos. They both agree they have happened upon a submarine and that further investigations are required.

The trawler’s fishing net proves to be a problem, so Stathis sets to work on it over the ensuing dives. His efforts eventually reveal a compass on the conning tower. It is incased in brass and mounted on a gimbal that had long since been jammed and overgrown with encrustations. While trying to remove the growth and grime from the glass dome, it bursts and everything is suddenly enveloped in a confusion of erupting bubbles.

“Down there, in the silence of the deep… all alone but for your own rhythmic breathing, an unexpected explosion is startling, even terrifying,” Stathis recalls. “So, it took me a few moments to recover and work out just what had happened.”

The ordeal soon pays dividends. “I was looking at the newly exposed compass dial when I noticed an unmistakable symbol. Emblazoned there as clear as day was a War Eagle. Its powerful claws were clasping a NAZI Swastika. It meant that I was actually standing on a WWII German submarine!”

“Down there, in the silence of the deep… all alone but for your own rhythmic breathing, an unexpected explosion is startling, even terrifying”

– Stathis Baramatis

Although Stathis took little time to inform the German Embassy in Athens, they showed no interested in the find whatsoever. This was particularly unexpected, given that the remains of the U-boat’s officers and crew were likely to still be on-board. Stathis then proceeded to file a joint recovery application with salvage company owner Yiannis Panagos, but this was rejected by the Greek authorities. Yiannis Panagos later lodged a separate request to purchase the submarine for scrap, but this was also unsuccessful. With all options thus being exhausted, Stathis was forced to drop the matter so as to continue to provide for his family.

Then, just as this amazing discovery of a virgin U-boat wreck seemed to buried by indifference and bureaucratic obscurity, a new impetus was found in the form of a 1991 investigative newspaper article by journalist C. Karagiorgas. Although the exact location of the U-boat remained undisclosed, its existence had finally become known to the local tech diving community. Recreational diving had yet to deregulated in Greece, so only a hardy few professionals dived the local waters at that time. Nonetheless, such was the allure of a German U-boat that the mid-90’s saw the wreck relocated and several dives undertaken. The race for the U-boat’s identity began in earnest.

Even as research-diver Aristotelis Zervoudis was on the verge of the same finding, it was fellow wreck hunter Kostas Thoctarides who was first to correctly identify the wreck as U-133. It had been a full decade since its initial discovery. In the ensuing years, more information has come to light and the complete story can now be told.

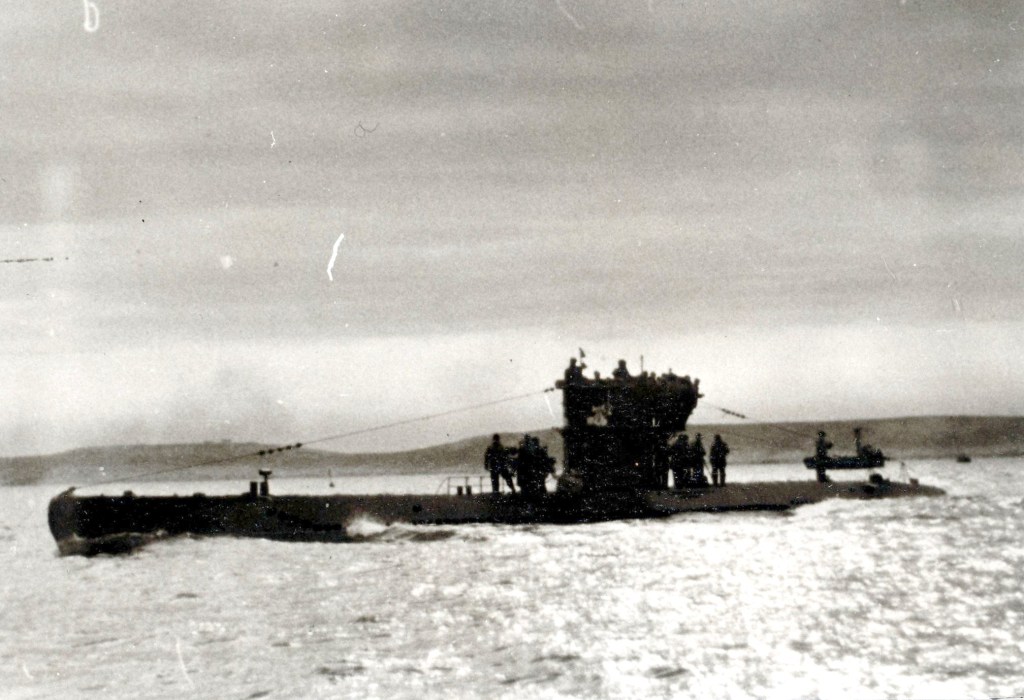

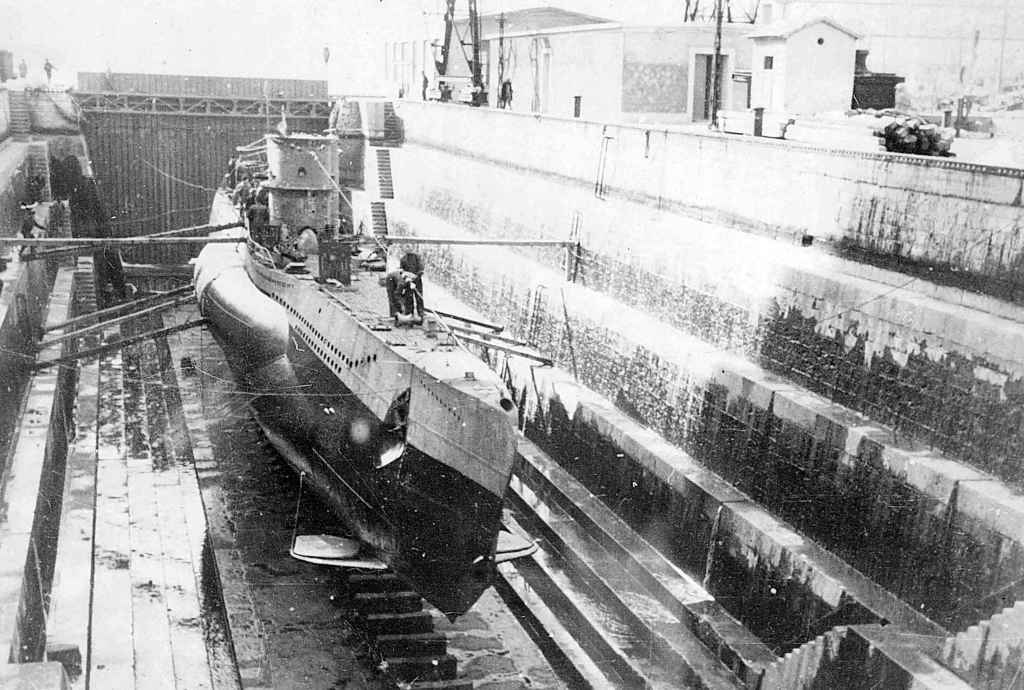

U-Boat Base on the Greek island of Salamis

Source: The U-Boot Museum, Cuxhaven ©

Source: U-Boot Museum, Cuxhaven ©

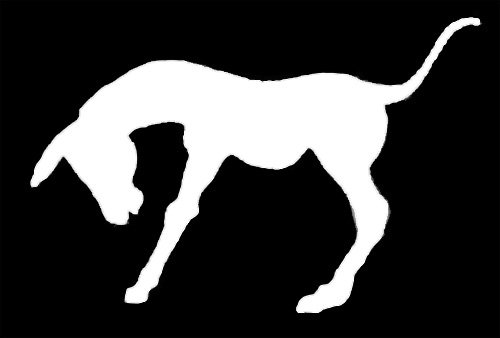

The war emblem of the German 23rd Submarine Flotilla, based on the Greek island of Salamis. The escutcheon depicts a donkey, the Flotilla’s mascot.

Source: Georg Hoegel ©

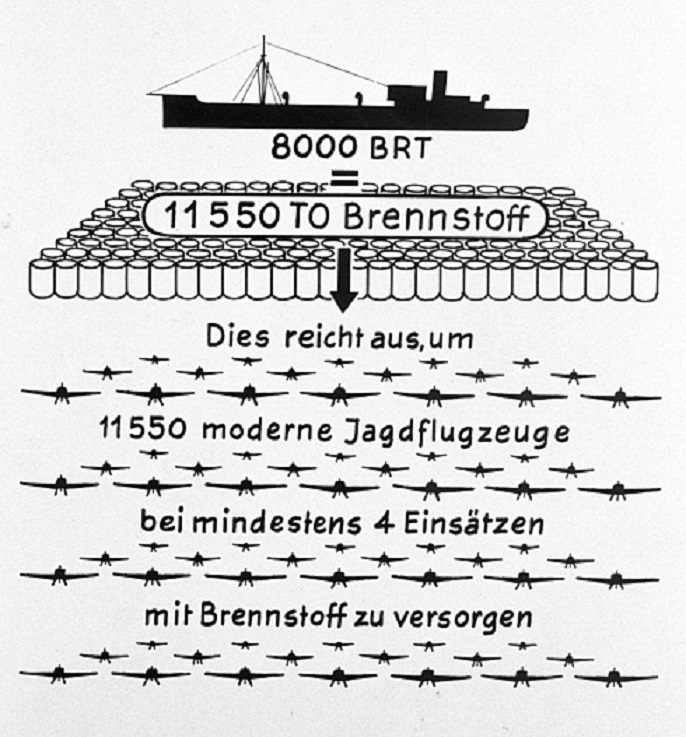

The lethality of German WWII U-boats in the Atlantic is well-known. Britain was almost single-handedly brought to its knees by the havoc ‘Wolfpacks’ wrought on Allied convoys and transatlantic supply routes. Perhaps lesser known is the crucial role U-boats played for the Germans in the Mediterranean. A strong British naval presence in the region and the general ineptitude of the Italian Navy had severely compromised Axis supply lines from Europe to Lt Gen. Erwin Rommel’s Afrikakorps in North Africa. This seriously threatened his great push eastward towards Egypt and the quest for the Suez Cannel. As the ultimate prize was access to the Arabian oil fields which lay beyond, something drastic had to be done redress such an unacceptable balance.

Field Marshal Erwin Rommel called for the transfer of U-boats to the Mediterranean to enforce a maritime blockade and isolate resistant British forces in 'Fortress' Tobruk. Source: Bundesarchiv ©

B.d.U. (Befehlshaber der U-Boote) Admiral Karl Dönitz, Commander-in-chief of Submarines. He later replaced Hitler, albeit temporarily, as the Führer of the Third Reich. Source: Bundesarchiv ©

Under direct orders from the ‘Führer’, six Type VIIc U-boats ran the perilous gauntlet of the British controlled Straits of Gibraltar in September 1941. More were soon to follow and two Kriegsmarine Submarine Flotillas, the 23rd and the 29th were established – the first and former being based at a commandeered naval facility on the Greek island of Salamis. Their predacious effect was immediate and the Allied supply lines from Alexandria and Port Said to the British and Commonwealth Forces in besieged Tobruk disrupted to good effect.

Lieutenant Hermann Hesse, born in Cologne, Rhineland on 10.3.1909, transitioned from Luftwaffe training to the Kriegsmarine. He served on WESTERWALD and KARLSRUHE before submarine training from Oct. 1940 to Feb. 1941. Commander of U-133 from 5.7.1941 to 1.3.1942, he later worked at the Admiralty of Submarines. Returning to sea as U-194’s commander on 1.8.1943, his submarine was sunk in the North Atlantic, south of Iceland, on 24.6.1943, by depth charges from a Liberator aircraft. Source: Dimitri Galon ©

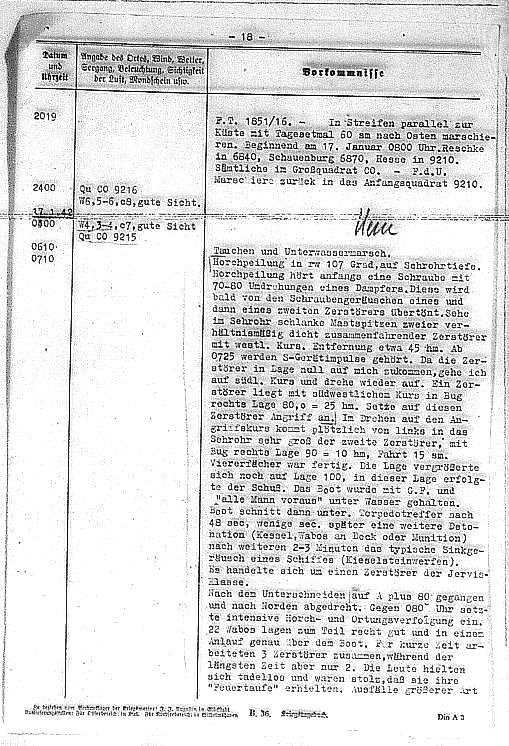

Among their number was U-133. It had been redirected from the Atlantic at the beginning of its second war patrol and despite being spotted and chased down, its captain, Lt Cdr. Hermann Hesse successfully made it through the British picket at Gibraltar on the night of the 21st of December 1941. Waylaid for a time in Messina, Italy, because of propeller shaft problems, U-133 was in its designated hunting ground off the Egyptian coast on the 17th of January 1941 when its hydrophone picked up Allied convoy MW-8B heading from Alexandria to the besieged island of Malta. Lt Cdr. Hesse fired a full salvo of torpedoes at one of two destroyer escorts in his periscope sights, sending the 1,920 ton L-Class British destroyer, HMS GURKHA II (G63) to the bottom. Miraculously, the second destroyer managed to save all but nine crew members.

Source: U-Boot Museum, Cuxhaven ©

A new Commander at the helm

Thus primed, U-133 finished its second war patrol at the Naval Base on Salamis where it was incorporated into the 23rd Flotilla. Accordingly, Lt Cdr. Hess relinquished his captaincy and the mascot of a kicking donkey – in reference to the island’s large population of wild donkeys – was painted onto the submarine’s conning tower. Despite having no combat experience whatsoever, U-133 was given to 26 year old Lt. Eberhard Mohr. Under his command, it set off on its third war patrol just before dusk at 18:00 hrs on the 14th of March 1942. Within an hour, the submarine would be lost with all hands.

The last commander of U-133, Lt.z.S. Eberhard Mohr (Düsseldorf 1915 – Aegina 1942). On the day he took command, Mohr was 26 years old and had only served in submarine training units. The first war patrol in which he participated and whose responsibility he bore, was the third and final war patrol of U-133. It was destined to last only an hour. Source: Dimitri Galon ©

Notice the emblem change to a donkey. Source: U-Boot Museum, Cuxhaven ©

The event was witnessed by lookouts of the Kriegsmarine 603rd Coastal Artillery stationed at Cape Tourlos and duly recorded (somewhat dispassionately) in their War Diary:

“18:55 hrs: The lookout at Tourlos reports a vessel heading south. It is identified as a submarine.

18:57 hrs: A flash and eruption of water, an explosion is heard immediately afterwards. The submarine has disappeared.”

Source: Dimitri Galon ©

U-133 Down!

What had caused such a violent and unexpected destruction?

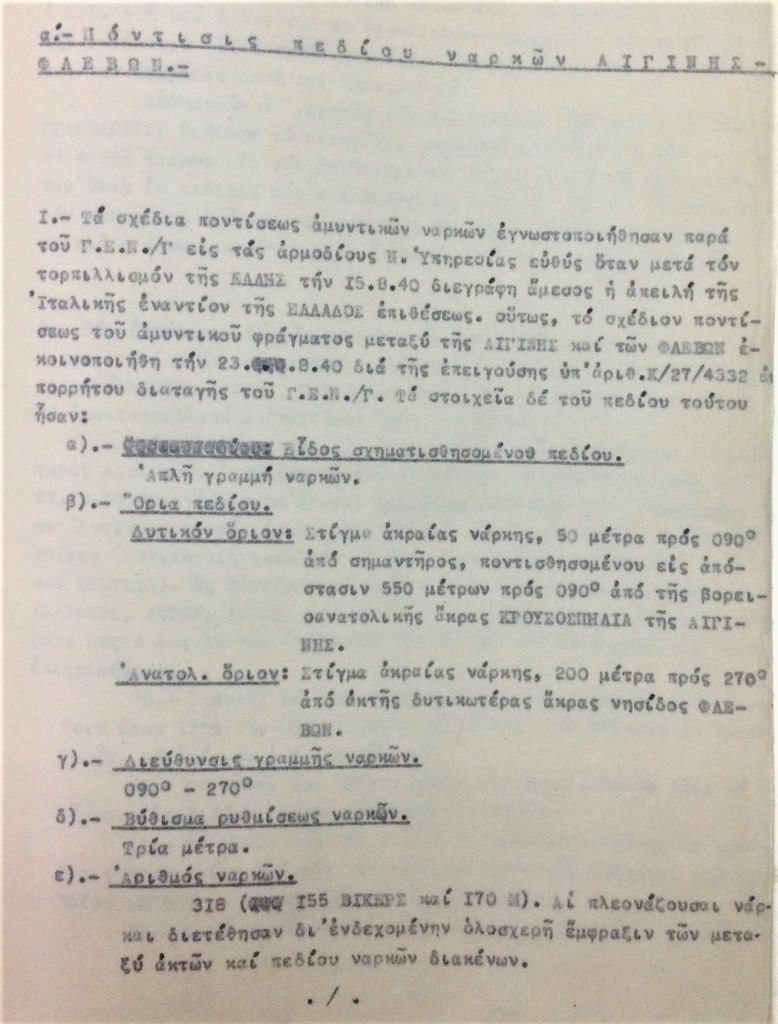

As a defensive measure to safeguard strategically vital areas, including Athens and the Port of Piraeus, the Royal Hellenic Navy secretly laid minefields in the Saronic Gulf just days after the Italians declared war on Greece on the 28th of October 1940. The largest was between Cape Tourlos on the island of Aegina and the islet of Phleves, located just off the mainland. It created a formidable east-west barrier right across the Gulf, but ended up doing nothing to stave off the relentless German war machine.

Following the occupation of Greece in April 1941, these minefields were simply incorporated into Axis defence plans. However, they proved highly problematic – mines would shift or even detach from their moorings and wash up on the beach or drift randomly around on the surface, posing grave danger to all concerned. On the 29th of March 1941 – just days before the Germans arrived – the Royal Hellenic Navy salvage tugboat, MIMIS (formerly JANE JOLLIFFE) fell prey to the Tourlos-Phleves minefield, with the loss of 23 men. So too did a hapless Greek caique on the 18th of January 1942.

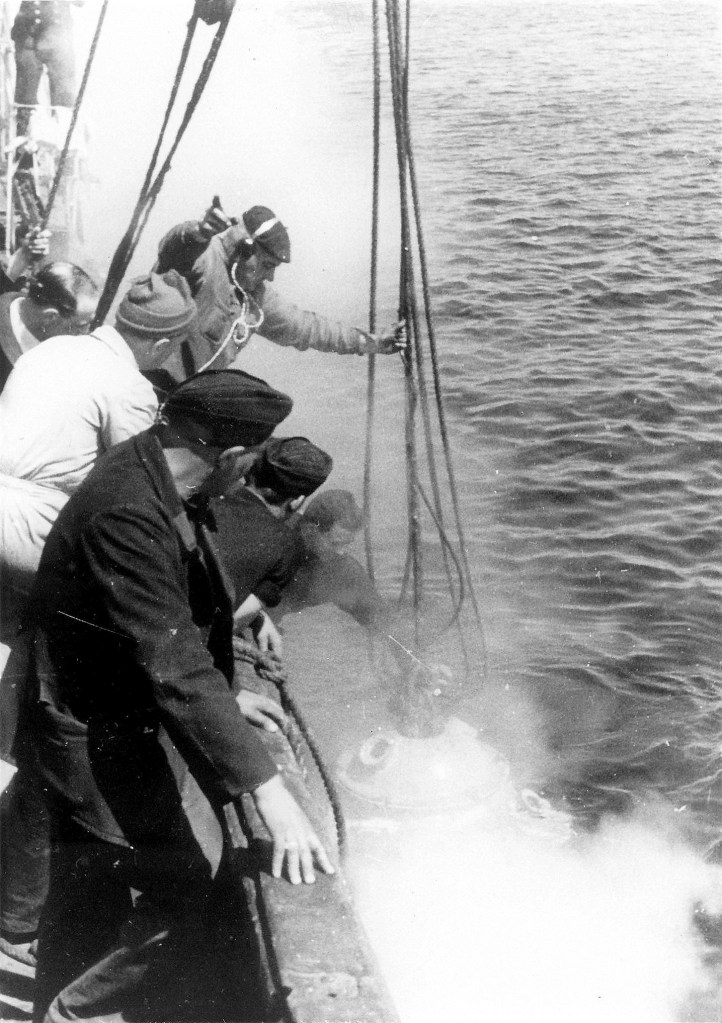

Confirmation that U-133 had indeed suffered the same fate required the logistical help of the Italian Navy. Despite the technical and diplomatic challenges involved, submarines were highly valued weapons of warfare and any chance of retrieval had to be investigated. Italian diver Lt. Enzo Biagi was duly sent down in a diving bell on the 4th of April 1942. He reported extensive damaged by an explosion consistent with that of a shipping mine. U-133 was beyond recovery.

Although a new arrival in Greece, Lt. Mohr must have been briefed about the minefield and its dangerous quirks. Consequently, blame for wandering into the hazardous area fell heavily on the young Lieutenant’s inexperienced shoulders. A cynical axiom in military circles is that “It’s only when things go horribly wrong, that they start handing out medals.” So it was with Lt. Mohr, who received a posthumous promotion to Lieutenant Commander shortly after the loss of U-133.

However, there was another element in play that no one seemed to recognise at the time. Deeper investigation into Attica’s German Naval Defense Administration records has since revealed that twelve days before the demise of U-133, a cargo ship inadvertently hit a buoy located off Cape Tourlos, thereby destroying its signaling lamp. In spite of it being the buoy which indicated safe passage through the minefield, it was not replaced until a full six days later – and only then with a simple surface marker.

Given that the sun had set forty minutes before the disaster and it was two nights before the next new moon, it can only be assumed that Lt. Mohr and/or his lookout crew simply failed to see this surface marker replacement in the dark. They were to pay for this understandable omission with their lives.

If there is any irony to the story, it is that at little earlier on the same ill-fated day, reports of an Allied submarine in the Saronic Gulf had prompted the German Naval Administration of Attica to send two coastal patrol vessels into the area. They were waiting for U-133 one and half nautical miles on the other side of the minefield – the intention being to safeguard the submarine’s passage out of the Gulf and into the wider Aegean. Had there been any survivors after the disaster, they could have been rescued within minutes.

In more recent times, it is understandable that there are no holiday brochures offering U-133 as a diving destination. By international law, it is a designated war tomb and cannot be interfered with.

Diving U-133

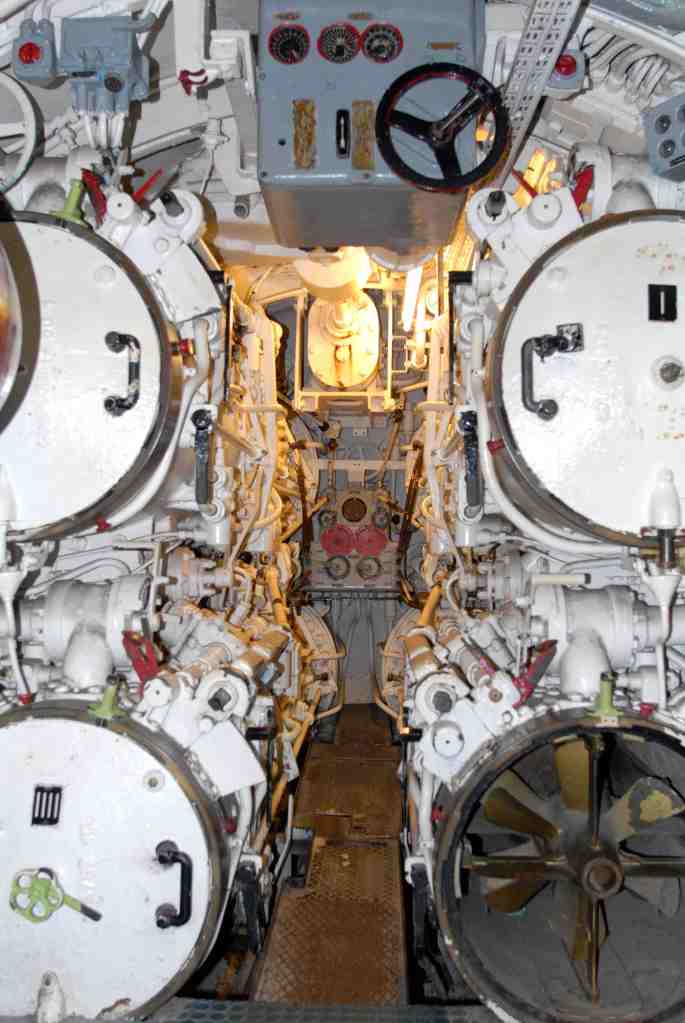

In any case, because it is located nearly two nautical miles off Cape Tourlos at +70 metres in waters known for currents, it is definitely not a dive for the inexperienced or faint-hearted. Nonetheless, for anyone lucky enough to experience this unique time capsule for themselves, the conning tower makes an obvious point of reference from which to start exploration. The air observation and attack periscopes (both lowered in their protective sheaths) can be clearly seen as one approaches. They are not vertical, which accentuates the fact that the submarine is resting on the bottom, port side down, at an angle of about 30 degrees.

Hovering directly above the conning tower, the base of the UZO (U-Boot-Zielobjektiv) is still distinguishable, despite thick encrustations. Special binoculars (with night vision capability) mounted on the UZO were, like both periscopes, linked to an onboard electro-mechanical torpedo data computer manufactured by Siemens. This worked out firing solutions for the fire control system and was absolutely cutting-edge in its day. Type VIIc U-boats also had radio direction finding capability and the scant remnants of the loop aerial base can be seen. However, the compass is missing from its encrusted gimbal, having been removed by Stathis Baramatis in 1986 as tangible proof of discovery. Unsurprisingly, the hatch on the conning tower deck is fully open, confirming that U-133 was on the surface when disaster struck.

Moving aft of the conning tower, the ‘Winter Garden’ area is barely discernible. This is where the 20 mm anti-aircraft FLAK 30 gun was located. However, the railings have corroded away and only the completely encrusted mounting now remains. Sadly, the gun itself seems to have been pilfered by an unscrupulous diver.

In front of the conning tower is the 88 mm deck gun, covered to this day with a large piece of the trawler net which snagged on the submarine back in 1986. Now one continuous mass of marine life, the actual gun is barely distinguishable. Along the hull, all the wooden decking has long since disintegrated, leaving sizable gaps from which the space between the casing and the pressure hull is visible and fish dart non-committally.

Forward of the deck gun, the entire bow section – about a quarter of the submarine’s total 67.1 metre length – is simply missing. The mine struck under the forward torpedo room, which was also an area that doubled as the crew’s quarters. With water being such a dense medium and virtually incompressible, the main force of the blast was directed upwards and onto the hull. This literally blew the front of the submarine off, leaving a cross-sectional hull breach. However, the twisted metal and marine growth found there today negate any notion of wreck penetration.

Source: Dimitri Galon ©

Swimming back down the submarine to the stern reveals both three-bladed propellers, with the port prop resting on the seabed. The course rudders, the vertical support shaft, as well as the rear hydroplanes are also distinguishable, although thickly covered in ever-present marine growth. But an unexpected surprise is to be beheld. Underneath all this and perpendicular to the main body of the submarine is the missing bow section.

This odd arrangement can be explained. Following the explosion, the detached bow settled on the seabed first, shortly followed by the remainder of the submarine. Somewhat perversely, the stern came to rest on top of it.

Closer inspection of the starboard side of the bow section (the port side being partially buried in sand) reveals torpedo tubes one and three are closed. As U-133 was just starting off on a war patrol, it would have been fully laden with fuel, food supplies and munitions. Fourteen torpedoes must have been on board, none of which would have been loaded into the bow tubes as the submarine was cruising in friendly waters when fate dealt its cruel blow. Most were stored precisely where the mine struck. Whether or not these contributed to the powerful explosion will never be known. Type VIIc boats also had an aft torpedo tube which could only be loaded externally while the submarine was on the surface. Doubtless, a single torpedo loaded in 1942 remains encased there.

Various objects are scattered on the sandy seabed around the site. The most notable of which being a torpedo-like compressed air cylinder directly in front of the breach. This had been located directly above the forward torpedo room and living quarters but somehow became separated in the explosion and sinking. Moreover, one of the anchors can be found near the stern of the submarine. However, most other objects have been made indistinguishable by the force of the original explosion or by subsequent marine encrustation and corrosion.

Left: A German propaganda poster with the exhortatory caption: ‘Voluntarily join the Kriegsmarine’. Right: A German postcard depicting the badge of the U-Boat War Badge (U-Boot Kriegsabzeichen). Acquisition required participation in two combat patrols. Source: Dimitri Galon

Although U-boats certainly had the upper-hand in the first years of the war, the eventual losses were simply staggering. Sixty-five U-boats were sent into the Mediterranean, yet not a single one survived. Indeed, to serve on a Kriegsmarine U-boat in any theatre of war was a virtual death sentence. Of the 40,000 who enlisted or were recruited, 30,000 souls were lost. Of the 863 of the U-boats sent on war patrol, 784 met a catastrophic end.

There are a total of five other U-boat wrecks in Greek waters. However, U-133 is the only one accessible to divers. For this reason, it is also the only one which has been unequivocally identified.

U-133 stands as both a rare and important artefact because it embodies the events which took place in Greece and the wider Mediterranean during WWII. Yet its value transcends that of an object of historical interest because it also entombs the members of its crew. They were all young men caught up in the fanatic visions painted by a failed Austrian art student and disgruntled WWI corporal who went by the name of Adolf Hitler. The extreme national chauvinism which followed led to Germany’s rearmament, its attempts at conquest and genocide, not to mention the instigation an unprecedented global war which killed millions and affected many millions more. U-133 was one of the instruments of that tragedy. Seventy-eight years later, its remains continue to be a reminder of the needless bloodshed and loss of life caused by promoting intolerance and wilfully manipulating beliefs. As such, it is a dive far deeper than anyone who makes it ever expects.

Delve Deeper

Take a look at the primary source records and other associated items yourself to delve deeper into the story:

Source: War diary of the Greek Royal Navy, Volume A, Service of Naval History, Votanikos, Athens.