A personal view by Gav Don

Part II of II

This article also appears on the HMS Triumph Association website.

Discovered by shipwreck hunter extraordinaire Kostas Thoctarides in 2023 after a 25-year quest, the June 2023 revelation of HMS Triumph in the Aegean grabbed global attention. Join former Royal Navy officer Gav Don as he explores its fateful final day.

In the first instalment of this two-part article, Gav Don guided us through HMS Triumph’s drop-off of SOE/M19 agents at Antiparos and the subsequent failed attack on Tugboat Taxiarchos near the Greek mainland. Now learn what happened in the final hours of the ill-fated British submarine…

Reloading the torpedo tubes

Triumph had eight torpedo tubes – six inside her pressure hull, and one each side of the bridge, but outside the pressure hull. She usually fired her internal torpedoes because these could be withdrawn from the tubes while submerged for checking and maintenance during a patrol by the torpedo maintainers, which made them more reliable.

There was a serious risk that a badly-maintained torpedo would suffer from a gyro failure (the gyro kept the torpedo on a straight track) and circle back after firing to hit the submarine which fired. We know that accidents like this actually happened. A rogue torpedo once came within 6 feet (1.8 m) of sinking HMS Torbay, which only survived because she had dived immediately after firing. The men in Torbay’s control room heard her own torpedo crossing her hull a few feet over their heads.

The torpedoes in the external tubes were less reliable, and were generally saved for ‘all out’ attacks (like Triumph’s earlier attack on the cruiser Bolzano at maximum range) or for attacks after all her internal torpedoes had been fired.

As far as we can tell from German records, she probably made only one other attack during her patrol from Dec 31st to Jan 9th. We don’t know for sure how many torpedoes she fired, but the probable number is two or three.

On the morning of Jan 9th, before the Taxiarchis attack, she would therefore probably have had six torpedoes in her internal tubes, and two or three unused reloads in her torpedo stowage compartment. We know that she fired four torpedoes on Jan 9th – three are sitting on the seabed and the fourth blew up on shore. After the attack, she would, therefore, have had two loaded tubes, four empty ones, and two or three reloads waiting to be fed into the tubes. Two of these reload torpedoes were inaccessible, sitting on racks below the deck plating of the torpedo stowage compartment, which would have had to be taken up for the reload. The deck plates can be seen in the photo of a T-class torpedo stowage compartment looking aft (see Photo 3), with a torpedo on the right, and the arms that fold down to slide the torpedo into alignment with their tubes.

This is in fact HMS Alliance, but the A-class were in most respects identical to the T’s internally.

The photo shows a pristine and empty compartment. In reality, the torpedo stowage compartment on patrol was a mess of provisions, hammocks, canoes, spare gear, clothing and anything else that needed a home, for the torpedo stowage compartment was the largest compartment in the boat.

Photo 4 depicts the torpedo stowage compartment of one of Triumph’s sisters (HMS Trident) in 1942 showing it in everyday use – and all the kit that would have to be cleared to get the bottom two reloads into the tubes, whose inner doors can be seen in the tube space in the middle of the picture.

CO Lt Johnny Huddart would probably have concluded that there was little rush to reload. If a new target appeared on the run to the west, he would not want the reloading process to get in the way of a snap shot with his last two torpedoes, so no point in getting on with that quickly.

Once the run southeast began, standard operating procedures forbade any attacks en route in case they alerted the enemy to the presence of the submarine, which would make the midnight rendezvous much more dangerous.

It is therefore likely that he ordered a delay to the tube reloading, securing from Diving Stations at 10:30 hrs to allow the off-watch crew to sleep before the watch change at 12:00 hrs. Huddart knew that a long and stressful night awaited his crew. He also knew that men were asleep in hammocks in the torpedo stowage compartment, and would have to be disturbed for the reload. Finally, a midnight supper snack of ham sandwiches was generally served at midday, either side of the watch changeover at midday, and would distract the reloading team.

I think that he and 1st Lt Michael Janvrin (Second in Command and in charge of the boat’s routine) decided to delay the torpedo reload until after the watch change and the midday sandwich, and until after Triumph was sailing calmly on 140 degrees at 80 feet (24 m), safely out of sight, unbothered by the enemy, with her crew rested and fed.

If that logic is correct, then the reload task would have begun at about 12:15 hrs. The track plan probably looked like this (Map 5).

Jump forward, work back

We now need to jump forward an hour or two, and work back from what we know happened at Triumph’s demise.

To cut a long story short, Triumph ended up on the seabed 666 feet (203 m) down, missing almost a 100 feet (30 m) of her forward pressure hull, 4 nautical miles (7.4 km) northeast of the island of Ag Georgios.

We know that she sank on a southeast track, which is consistent with a course of 140 degrees.

I have seen the video of the forward part of her wreck (the video is not in the public domain).

It shows that the pressure hull and casing forward of the gun platform has collapsed inwards, as far as about the torpedo loading hatch, and that the hatch itself, and all of the 100 feet (30 m) of pressure hull forward of that, has simply disappeared, except for a shallow ‘scoop’ of the lower fifth of the pressure hull, a bit like a marrow spoon.

The damage is illustrated below (Diagram 1).

What could have inflicted such a traumatic blow?

Not a mine.

Several wrecked submarines showing fatal mine damage have been photographed which we can use as comparatives.

When a submarine strikes a mine, the blast occurs next to its pressure hull, which is something approaching an inch (2.54 cm) thick of high quality steel. 90% of the mine’s blast energy vents away from the hull, harmlessly into the sea above, below and on the other side of the mine.

Only about one tenth of the mine’s explosive power is absorbed by the submarine’s hull. This is usually enough to open a small crack in the pressure hull. The dynamics of sea pressure, flooding rate and a submarine’s inherent lack of buoyancy then quickly sink the boat. This is true even if the mine is a big one. If Triumph had simply struck a mine, we would have found her more or less intact, with a crack in her fore ends.

What has actually happened is that Triumph’s entire forward third has gone – disappeared. There must have been a massively larger explosion to cause that to happen.

The only candidate for that much larger blast is one of her torpedoes.

Mark VIII torpedoes

The Mark VIII torpedo was a powerful weapon.

The torpedo itself is 18 feet (5.48 m) long and weighs 1.5 tonnes – think a family car, squished down into a 21 inch (53.3 cm) tube.

At the front of the torpedo is the warhead – 661 pounds (300 kg) of high explosive – which is enough to cut a ship in half. Photo 5 depicts warheads of a similar size to Triumph’s Mark VIIIs.

Photo 6 shows a 2,500 tonne ship hit by a 661 pound (300 kg) torpedo warhead. Triumph was 1,600 tonnes.

If one of Triumph’s torpedoes detonated inside her, we would see exactly the damage that is, in fact, visible.

100% of the blast would be absorbed by the pressure hull, and the weakest part of that (the upper three quadrants) would give way to and vent the blast, leaving the lower quadrant still in place. This is what the video shows.

The blast would destroy the watertight bulkhead at the aft end of the torpedo stowage compartment, which would then stop supporting the pressure hull and casing above it, and water pressure would cave the casing in downwards, which again is what the video shows.

But would a torpedo detonate unintentionally?

Mark VIII torpedoes were famous for their reluctance to blow up at the wrong time.

While the Torpex warhead was extremely violent, it was also very stable, and could only be induced to explode by igniting a smaller explosion inside the warhead, with a more sensitive explosive. This explosive, too, was still relatively insensitive, so it too needed its own explosive detonator, a smaller and more sensitive trigger charge.

So, to set off a Mark VIII, one had to trigger not one, but two prior explosions in exactly timed sequence, a primary charge and a secondary charge.

To add even more safety, the four primary charges sat in small tubes (think of brass test tubes) held on a spring outside the secondary charge, so to fire the torpedo, the primary charge had to move (under spring power) into matching holes in the secondary, and then get triggered by the strikers.

If the more sensitive primaries detonated by accident, they would do so outside the secondary, and so not set off the warhead.

I can find no example of a Mark VIII detonating at the wrong time in any wartime narrative, even those sitting on the burning deck of a cruiser after an action.

Indeed, Triumph’s own Mark VIIIs resisted spontaneous detonation when a 551 pound (250 kg) mine exploded ten feet away from them on the surface in the Heligoland Bight in 1939.

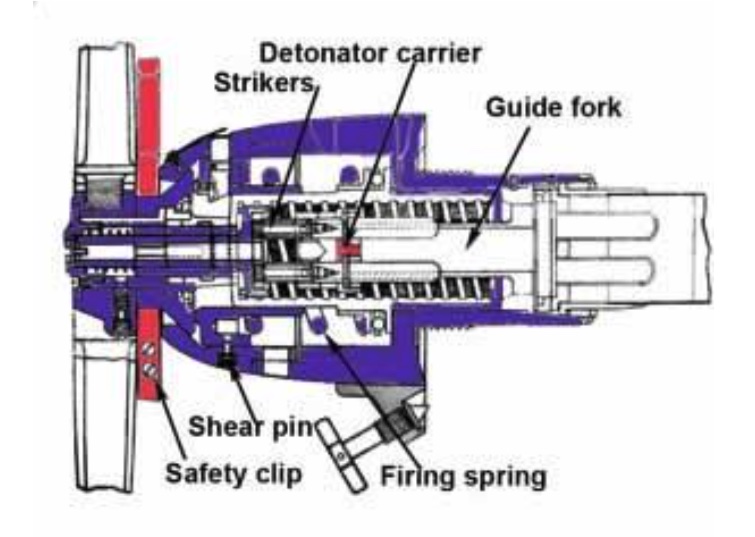

The trigger charge in a Mark VIII was initiated by four sharp steel spikes called ‘strikers’, which were held on a powerful spring in an assembly in the nose of the torpedo. The striker spring was kept back by a shear-pin and connected to a five-armed steel star sticking out of the torpedo’s nose.

On hitting a target, the star’s arms would push its core into the nose of the torpedo, breaking the shear-pin and releasing the firing spring. This inserted the primary charges into their slots in the secondary, where, a millisecond later, the strikers on their spring would slam home into them detonating the primaries, and then the secondary charge, and then in turn the main charge.

The reason for having five spikes on the star was to make sure that the warhead detonated even if the torpedo struck its target at an oblique angle.

The whole assembly was called ‘the pistol’.

Diagram 2 is a schematic of the pistol. It is possible to see two of the four strikers, poised just above their primary charges, which slot into the tubes in the secondary on the right.

While a torpedo was stored in the torpedo stowage compartment, its pistol was kept in the magazine. With the pistol safely stowed thirty feet away from the torpedo, there was no way anything could set off the secondary charge.

When a torpedo was to be loaded into the tube, the pistol had to be gently screwed into the torpedo’s nose and its safety clip removed. From this point on, a sufficient impact on the five steel star legs would fire the torpedo.

The springs were designed so that the pistol needed just a 5 g (i.e. g force) impact to set it off. That is a low impact – about the same as a car driving into a brick wall at 5 mph (8 kph) – but large enough to prevent the pistol from being triggered as the torpedo accelerated out of the tube.

In 1941, Mark VIIIs had no ‘run distance’ safety mechanism. The torpedo was live in the tube, and would detonate at any distance from the tube if it hit a hard enough target.

Back to Triumph

The massive damage shown in the video can only be explained by the detonation of a Mark VIII warhead inside the boat.

So, how did that happen?

We need to return to the boat at about 12:15 hrs on 9th January.

She is on her 140 degree (southeast) track at 80 feet (24 m), on electric motors at 3.5 knots (6.5 kph). The forenoon watch (08:00 to 12:00 hrs) has been handed over to the afternoon watch (12:00-16:00 hrs). Everyone on board has enjoyed a lunchtime snack of a ham sandwich and some tinned fruit cocktail. After 14 days at sea, the bread is on its last legs. However, Chef O’Brien might bake some more that night on the way down to Antiparos.

The off-watch men are heading to bunks and hammocks in their messes, but the torpedomen have a task to do: arm and load the two or three remaining torpedoes into their tubes. By 12:30 hrs, they have rigged the folding arms to slide the first reload into its tube, ignoring the moans of messmates who want to sling hammocks and catch some zeds.

It is heavy work – each torpedo weighs 1.5 tonnes – but this is something they have done a hundred times before, so they work swiftly. When the first torpedo is lined up with its tube, and has been given some basic checks (air pressure, oils topped up, depth and speed settings as ordered, fastenings all tight, screws, rudder and hydroplanes free to move), its pistol is gingerly removed from its beige green wooden box painted with yellow stencils, and is gently screwed into the nose of the torpedo.

The red safety circlip is removed and returned to its box. The torpedo is now live, and the men’s movements become gentle and slow. With ropes fastened to its tail, the torpedo is now heaved gently towards the open door of the tube. The pistol’s firing arms have a diameter well short of the torpedo’s 21 inches (53 cm), but even so, if one of them hits anything with anything more than a gentle bump, it’s curtains.

It is safe to conclude that the firing arms did, indeed, hit something with more than a gentle bump.

But what, and why?

Time for another map.

The second mine-line

We know, from post-war records, that on 4th December 1941, Barletta laid a second line of mines. This line, 108 large 551 pound (250 kg) mines, set at 39 feet (12 m) deep, was laid exactly across what would become Triumph’s 140 degree course to Antiparos.

If my deductions so far are valid, then Triumph sailed across this mine line at about 12:30 hrs on the 9th, just after Petty Officer Frank Collison removed the safety clip from a torpedo pistol and just before it was hauled safely into its tube.

The obvious first question echoes the one from earlier that day – did Triumph know about the second mine line from a QB signal?

I suspect not. If she had, she would have taken a different track, probably west of Agios Georgios, or perhaps close along its east coast, but her wreck position shows she did not.

Also, the lines were laid within a few days of each other and were probably ordered in the same signal, so if Triumph did not know about the first mine line from an Enigma decrypt, she would not have known about the second one either.

If she didn’t know about the mines, did she see them on her MDU? The east-west line earlier in the day was laid more densely, and Triumph approached it obliquely at the same depth as the mines, making sonar detection easier and more likely.

For this second line, Triumph approached it at a depth at least 50 feet (15 m) and possibly a 100 feet (30 m) deeper than the mines. Triumph’s sonar dome was located at the front of her keel, deep under her hull, and it is possible that its ability to detect contacts above the pressure hull was degraded by the blanking effect of the hull.

Also, it is likely that the sound energy propagating from the transducer was designed to propagate in the horizontal plane, to prevent the sea surface from providing a myriad of false echoes. We know from an earlier Triumph patrol report that the MDU sonar provided false echoes from the rough surface water created by a tide rip off Rhodes, when she was near the surface.

It is quite possible that the MDU simply did not show the mine line.

Another obstacle may have prevented detection. The sea is not a uniform body of salinity and temperature. As one leaves the surface, salinity changes slightly, and so does water temperature. The borders between different layers of temperature and salinity act on sound energy like mirrors – the sound energy literally bounces off the joins between two different layers, like reflecting off a mirror.

The sea has a pronounced surface layer where solar energy makes the water slightly warmer (in this case, slightly less cold since it was January), where wind action mixes the water more actively, and where atmospheric evaporation increases salinity.

The lower boundary of the surface layer acts as a sonar mirror (which saved the lives of many boats under depth charge attack), and it is possible that the second line of mines lay above or on the border of the surface layer, while Triumph was below the layer, with the mines hidden from her MDU sonar.

In any case, the number of mines for the sonar to see was small. Approaching the mine line at more or less a right angle, and with the mines laid 394 feet (120 m) apart, even a fully functional sonar would see only one or two contacts ahead, which might easily be missed in the distraction of the watch handover and lunch.

Another possibility is that Triumph did see the mine line, but decided to dive below it. This was a perfectly normal procedure at the time. Indeed, the only way to get into Malta, which was surrounded by multiple minefields, was to dive below the mines and creep through. Triumph’s passage plan contained little ‘fat’ for delay, and to go around Agios Giorgios to its west would have added hours to the plan and made her miss her rendezvous, and, of course, there was no guarantee that mines would not be found west of Ag Giorgios too.

We can reasonably conclude, therefore, that Triumph crossed the mine line either unknowingly, at about 80-100 feet (24-30 m), or fully aware, at 200 feet (61 m). The former is more likely.

The most likely course of events, as she crossed the line, is that she snagged a mine mooring wire on her fore-planes. The mines were attached to a heavy sinker on the sea bed 600 feet (183 m) below by a wire cable. Triumph, 30 feet (9.1 m) wide, might easily snag one of these cables. The snagging of mine cables was mentioned often enough in the numerous memoirs of submarine captains to be predictable here.

Normally, the noise of a snagged cable would penetrate clearly, and terrifyingly, inside the pressure hull – a horrible metallic grating noise that could only be one thing. But not always, however. One memoir recalls a boat surfacing at night and seeing, to the horror of all, that she was towing a mine from her after planes and had been doing so for hours.

If she snagged a mine cable, even if she knew about it, there would be little she could do. She might try going astern – not easy when dived and not guaranteed to clear a snag. She might try stopping and adjusting depth with her ballast tanks, again not easy and no guarantee of success. She might, if nothing else worked, surface to try and cut the mine free.

On the surface, she would become painfully visible to sharp eyes on Cape Sounio and possibly a fully alert enemy flying around overhead, but surfacing might be the lesser of two evils. But surfacing would contain another lethal risk. With a mine snagged on her fore planes, as Triumph surfaced, there would be a significant risk that the mine would float on the surface just above her as she rose, and would make contact with the surfacing hull and detonate.

If CO Lt Johnny Huddart was fully aware of the mine, then one course of action might be open – one that was difficult and probably rarely, if ever practised, but possible. Triumph would go slow astern on one screw (to take her away from the mine field in a curve) and surface while going astern. On the surface, she would continue going astern, in the hope of towing the mine from her bow planes, but clear of the hull, while a man cut the cable free with a hacksaw.

In any event, if Huddart knew that she had snagged a mine cable, he would surely have stopped the reload and ordered the pistol to be withdrawn.

I think it is far more likely that Triumph did not know she had snagged a mine, because the cable was just stuck, not slipping, and making no noise.

As she sailed on at 3.5 knots (6.5 kph), the mine would have been dragged down towards Triumph by the flow of water. If Triumph was at 100 feet (30.5 m), there would be roughly 55 feet (16.8 m) of wire between her and the mine. So, as she sailed on unknowing, the mine would have been drawn down towards her hull, making contact somewhere above the crew messes forward of her gun platform.

Detonation…

An almighty bang just a few feet above the heads of the men inside. A huge impulse shock to the boat, which leaps violently downwards away from the blast. As the hull cracks open and high pressure water floods in, the shock of the explosion makes the armed torpedo leap out of its loading slide and crash into the rear end of the tube. The pistol’s star-arms hit the tube door violently, pushing them back to release the strikers, and a quarter of a second later the torpedo explodes.

The shock wave from the warhead detonation, moving at the speed of sound, takes only half a second to propagate through the boat. Any man standing up is thrown violently against a bulkhead, every cup, plate, spanner, becomes a violent missile flying around inside the hull.

The men in the fore ends would have had only half a second in which to realise what was happening as the torpedo leapt out of their control – barely enough to register, never mind think ‘Oh, F***!’ – before being torn apart by the torpedo explosion.

The men settling down to sleep in the three messes aft of the torpedo stowage compartment, the junior rates’ mess, the petty officers’ mess and the artificers’ mess, would have been hurled violently out of their bunks stunned, if even conscious.

Aft of that, the off-watch officers asleep in the wardroom and CO Lt Johnny Huddart in his cupboard-sized cabin would have been thrown out of their bunks, but might have had a second in which to realise that something very large had given Triumph a death blow.

With the forepart of her hull blown away, a wall of water powered aft, arriving only one or two seconds after the explosion (watertight doors were rarely closed under way). The water would have swiftly reached the watchkeepers in the control room, then the signallers in their communications office, then the on-watch stokers and electrical ratings in the motor room. No more than ten seconds later, the off-watch stokers in the stokers’ mess right aft would have been the last men to see the water wall arrive.

With the momentum created by sailing at 3.5 knots (6.5 kph), with only about 150 yards (137 m) between the boat and the sea-bed, and sinking like a 1,600 tonne stone, Triumph’s bows would have hit the bottom about 20 seconds after the explosion, by which time everyone aboard was already, sadly, dead.

And there she sat, until we found her in June of this year (2023).

One mystery remains.

The last mystery

The photographs show that one of her external torpedoes amidships has come part-way out of its tube. How did this happen?

At sea, the tube’s door was always shut, because the torpedo was armed, and its five pointed star trigger might impact a piece of debris and fire, or be triggered by a depth charge.

The torpedo appears to have no pistol. It might have been ripped off by a fishing net, but when you look back at the schematic (Diagram 2), you can see that the firing arms are really solid, and screwed tightly into a solid torpedo nose.

Another scenario is possible, and I think more likely.

The external tubes had a hard life – always wet, buffeted by waves on the surface, and under pressure when submerged. They had been in continuous service for over a year. If the hydraulic system for opening and closing their doors had malfunctioned, the door might have jammed open at some point in the patrol. If that happened (which is quite likely), then it would become essential to remove the pistol to prevent an accidental detonation, either from a random impact or during a depth charge attack. Removal would be easy, when surfaced at night, leaving an inert torpedo in the tube open to sea but not a danger.

Then, as Triumph collided with the sea bed at 3.5 knots (6.5 kph), pointing down at an angle of about 45 degrees, the momentum of the 1.5 tonne torpedo might easily make it slide a few feet out of its tube, leaving it for us to find, pistol-less, 81 years later.

Epilogue

So, there we have it. Some of the story is known, some can be deduced with careful analysis and external data. I believe that the narrative above is as close to the truth as we are going to get, unless some remarkable new piece of evidence appears.

There are other possible narratives, but with probabilities that are very much lower than this one. For example, the armed torpedo might have landed on its pistol for other reasons – a malfunction of the forward hydroplanes (something that is recorded to have happened to other boats) might have crashed Triumph into the seabed at the critical moment (this theory is partially rebutted by the fact that her after planes are in normal horizontal positions). Or the torpedo’s loading arms might have collapsed at the critical moment (but this would have dropped the torpedo on its body, not on its nose). Or the shear pin might have had a fault and failed at the crucial moment (but the sheer probability of a failure at that precise moment is vanishingly small).

Future evidential discoveries may open the door to other narratives. The missing parts of Triumph’s hull (100 tonnes of steel) and her missing torpedoes must all be lying in a debris field not many hundreds of metres from the wreck site, and perhaps one day we will send down another ROV to have a look.

But, with the evidence we have combined with what we know about her operations, I believe this narrative is far and away the best fit and the one most likely to be true.

Although her demise was a lamentable consequence of war, I take comfort from the likelihood that Triumph’s end was swift, relatively painless, and came as a complete surprise to her crew. I hope that the other families of those who perished do too.

The Author

The dedicated curator of the HMS Triumph Association website, retired Royal Navy Officer Gav Don has invested countless hours delving into the archives in a relentless quest to unveil the fate of HMS Triumph. His personal interest has intensified this mission, as his uncle was among those on board when the submarine was tragically lost, claiming all hands. To explore further insights into his discoveries, visit the Association’s HMS Triumph 1942 website by clicking here.

Acknowledgements

ww2stories.org would like to thank Planet Blue – ROV Services for their underwater images. A leading enterprise specialising in marine projects, it was founded in 1999 by award-winning professional diver Kostas Thoctarides. It offers expert solutions such as observation, inspection, repair, maintenance, and installation support. Check out their website here.

We value your opinion!

Your feedback is important to us. If you enjoyed this article and would like to see similar content, show your appreciation by clicking the ‘Claps’ icon below. Also, ensure you stay up-to-date with our latest articles by subscribing to our Newsletter. You’ll receive new posts directly to your email inbox. Thank you for your support!

‘History has to be shared to be appreciated’

Subscribe to our newsletter. We’ll keep you in the loop.